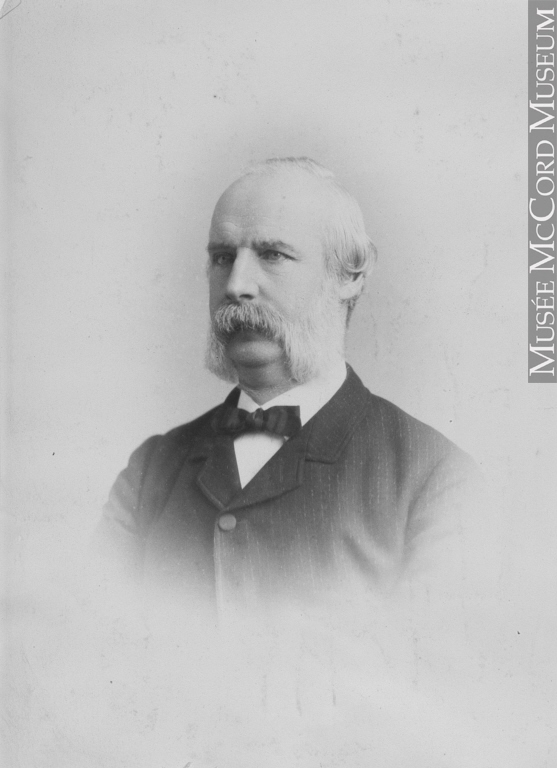

On May 21, 1887, the day after the president of the Bank of Montreal died following a short illness, the New York Times reported on his death, noting that “the effect on the stock market was naturally to depress Montreal stock, though to a smaller extent than might be expected.” Charles Francis Smithers, my great-great-grandfather, had been president of the Bank of Montreal for six difficult years and, according to a published history of the bank, was “noted for his devotion to business, his high principles and his brilliant direction of the Bank’s affairs during the trying period that had encompassed the building of the C.P.R.”

Charles was born in 1822 in Surrey, just across the Thames River from the City of London. He was the youngest son of merchant Henry Keene Smithers (1785-1859) and Charlotte Letitia Pittman (c. 1785-1861). As a young man, Charles moved to Waterford, Ireland, where he met Martha Bagnall Shearman. They were married in 1844.

He came to Canada in 1847 as the accountant of the Bank of British North America. He served in the Bank of Montreal’s Montreal office for seven years as accountant and sub-manager, he was sent to be manager of the branch at Brantford, Ont. for two and a half years and was then promoted to the management of the bank in St. John, New Brunswick. But there may be errors in this timeline. His eldest son was born in England in the autumn of 1847, so perhaps Charles preceded his wife to Canada, or perhaps the family crossed the Atlantic in late autumn. The couple’s next child was born in New Brunswick in 1849.

In 1858, Charles became an inspector and, in 1862, he was appointed joint agent of the bank’s New York Branch. At that time, the bank’s official history says, his “quiet and disarming manner concealed a knowledge of banking equaled perhaps by only one or two other officers of the Bank.”

He left New York abruptly in 1863 to become branch manager of the London and Colonial Bank in Montreal. Three years later, he returned to New York City as a private banker and he rejoined the Bank of Montreal as its New York agent in 1869. Charles, Martha and their growing family (they eventually had 11 children) lived in Brooklyn, where two of Martha’s brothers and their families lived.

By the time Charles returned to Montreal as the bank’s general manager in 1879, he had been its senior agent in New York City for 10 years. Some people had criticized the bank for indulging in what they saw as risky speculation in a corrupt market. At the annual general meeting of the Bank of Montreal in 1880, Charles explained the importance of its New York business, noting that all loans had been based on good collateral with ample margins; meanwhile, there was a chronic lack of capital in Canada, and many loans were made simply on the basis of the borrower’s good reputation.

In 1881, Charles was elected president of what was then Canada’s most important bank. Over the next few years he faced two big challenges. The first was to steer the bank’s involvement in the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway (C.P.R.) from Ontario in the east to the shore of the Pacific Ocean. The Bank of Montreal acted as fiscal agent for the railway, and it gave it loans for work in progress.

The C.P.R. project faced some political opposition and hostility from competing railway companies, and Canada’s overall economic situation was not strong at the time. But construction progressed rapidly and the railway needed a lot of cash. In 1882 — before the workers had even reached the mountains or tackled the rock and muskeg of northern Ontario — it cost $5000 a mile for delivered steel rails to Winnipeg. The railway spent some $99 million on construction and equipment, raising funds through a variety of sources, including the sale of stocks, mortgage bonds and land grants, and a $25-million government subsidy. The Bank of Montreal loaned the C.P.R. more than $11 million.

Charles’ second big challenge was to direct the reorganization of the bank’s pension fund. Prior to 1884, there had been a fund to support widows and orphans of bank employees, but there were no guaranteed pensions for retirees or payments to those who became unable to work through illness. That year, the board of directors and shareholders approved a full pension plan for employees.

In a eulogy for his long-time friend, Rev. Dr. Cornish called Charles “a man of integrity and honour.” Following the funeral at Emmanuel Congregational Church in Montreal, Charles’ body was transported to the train station by horse-drawn carriage, then placed aboard a special train to New York City. He was buried in Green-Wood Cemetery, Brooklyn.

Charles’ Siblings:

Charles was one of nine children, three of whom died young: Rosa Anne (1811), Henry Keene (1812-1874), Alfred (1814-1874), Francis Pittman (1815), Sophia Anne (1817-1883), George Clayton (1817-1821), John (1821-1893), Charles Francis (1822-1887) and Mary Keene (1827-1859).

Charles’ and Martha’s 11 children:

Charlotte: b. 1845, Waterford, Ireland; m. Joseph B. Learmont, no children; d.1934, Montreal, QC.

Charles Henry: b. 1846, London, England; m. 1. Amaryllis Boerum, three children; 2. Emily Brett, two children; d. 1912, New Hampshire, buried Brooklyn.

Francis Sydney: b. 1849, New Brunswick or Montreal (probably born in N.B., baptized in Montreal), m. 1. Louisa Bancroft, four children; 2. Mabel Stevens Bouse, two children; d. 1919, New York City.

Martha Dunkin: b, 1851, Montreal; m. Henry Dawson, no children; d. 1928, Brooklyn N.Y.

Emily: b. 1854, Brantford, Canada West; m. 1873, George W. Carr, one child; d. 1930, St. Petersburg, Fl.

John: b. 1856, Brantford, Canada West; m. Kate Brett, no children; d. 1912.

Elizabeth: b. 1858, Montreal; m. Walter Hemming, two children; d. 1931?, Montreal.

Clara: b. 1860, Montreal; m. Robert Stanley Bagg, three children; d. 1946, Montreal.

George Hampden: b. 1863, New York; m. Frances Cook, two children; d. 1933, Montreal.

Christopher Dunkin: b. 1865, Montreal; m. Mabel Brinkley, three children; d. 1952, Long Island N.Y.

Alfred: b. 1868 New York City; d. 1890.

These dates have been difficult to find. I started with the incomplete dates given in the privately published Smithers Family Book. In cases where I could not find actual birth and death records, the 1870 U.S. census and the 1861 Canadian census helped. Findagrave.com and headstones and records from Green- Wood Cemetery, Brooklyn and Mount Royal Cemetery, Montreal helped, and I have my own photos of the Smithers family plot at Green-Wood.

Photo Credit:

C. F. Smithers, Montreal, QC, 1881 Notman & Sandham II-62438.1 © McCord Museum

Sources:

Merrill Denison, Canada’s First Bank. A History of the Bank of Montreal, volume II. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1967.

Elizabeth Marston Smithers. Smithers Family Book, Institute for Publishing Arts, 1985.

“A Montreal Banker Dead” The New York Times, May 21, 1887.

See also:

Janice Hamilton, “Henry Keene Smithers, Non-Conformist,” Writing Up The Ancestors, Dec. 1, 2014. https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2014/12/henry-keene-smithers-non-conformist.html