There were no hints or family stories to prepare me for what I found in the 1851 Census of England. I was looking for my three-times great grandparents Henry Keene Smithers and his wife Charlotte Letitia (Pittman) Smithers in Sussex, England. I had already found their 1809 marriage record at St Martin in the Fields Church in London, and it had said that Charlotte was from Barnes, a parish located near the mouth of the Thames River. So when the census revealed that Charlotte was actually born in Antigua, in the British West Indies, I was surprised.

I was also curious. Was her father perhaps in the British navy, which had a large base there? Or did her family own a sugar plantation? The History of the Island of Antigua, written by Vere Langford Oliver and published in 1894, provided the answer: Charlotte’s ancestors, the Elmes family, had lived in Antigua for more than a century and had been planters for several generations.

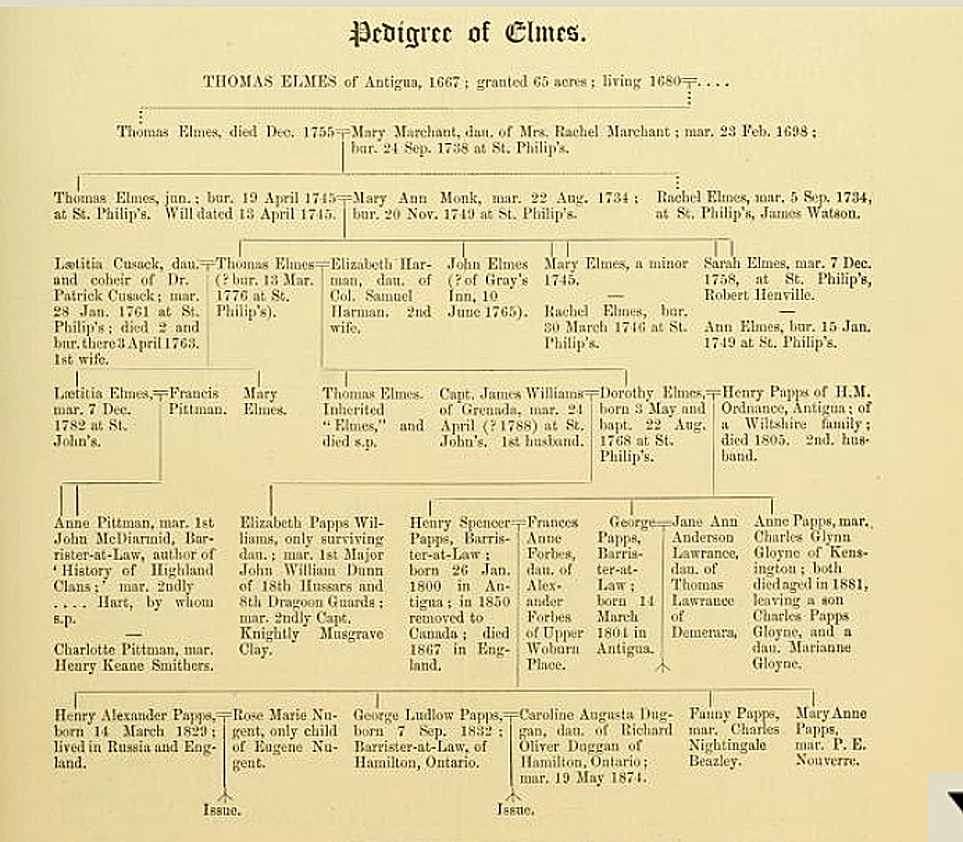

According to Oliver, the first mention of the family name appeared in 1654 when John Elmes owed £100 to the Dutch merchants. Thirteen years later, Thomas Elmes and four other people were granted 65 acres of land on Antigua. He acquired more land over the next dozen years. Oliver noted that St. Phillip’s Parish Church registered the 1698 marriage of the man who was probably his son or grandson: Thomas Elmes married Mary Marchant in 1698 and the couple had two children. He was buried in 1745.

Thomas Elmes II married Mary Ann Monk in 1734. Oliver transcribed his 1745 will, a document that revealed something of his personal and financial situation. To his wife he left ”a negro woman, a horse and jewels.” He made arrangements for money to support his four minor children, and he granted freedom to his mulatto boy Joicey – no doubt his son by one of the plantation slaves. His son Thomas was to inherit the estate.

He added a codicil a few years later, noting that his wife was now deceased and “my fortune increased and the number of my children decreased, therefore each child’s portion is to be £2000.” Thomas II died in 1755, leaving vacant his seat in the colony’s Assembly.

Thomas and Mary Ann’s son, Thomas Elmes III, married twice. In 1761 he wed Letitia Cusack, daughter of Dr. Patrick Cusack and Lettice Lewis. Oliver noted that the Cusack family was from Gerrardstown and Clonard in Ireland.

Letitia gave birth to two daughters, Letitia and Mary, but they were left motherless when she died in 1763. Thomas’s second wife was Elizabeth Harmon, with whom he had a son, Thomas, and a daughter, Dorothy. Thomas Elmes IV, was the last in the male line and had no children.

Thomas III’s and Letitia’s daughter Letitia Elmes married Francis Pittman in 1782 at St. John’s Parish Church, Antigua. The couple had two daughters, Anne and Charlotte. This branch of the family tree in Oliver’s book concluded with the marriage of Charlotte Letitia Pittman to Henry Keene Smithers.

Thomas Elmes III died in 1776. As for the Elmes plantation, it had been sold by 1770. In 1779 it was recorded as containing 149 acres. A volunteer researcher with the Museum of Antigua & Barbuda noted on an online message board in 2007 that the sugar mill on the property was still in good shape and that the property, located in St. Phillip’s Parish, on the island’s east side, is still called the Elmes Estate.

Research notes

The three-volume The History of the Island of Antigua, by Vere Langford Oliver, was published in 1894. Information about the Elmes family tree, on pages 243 and 244 of Volume I, can be found at https://archive.og/stream/historyofislando01oliv#page/243/mode/2up.

Oliver was a historian whose books are considered invaluable by people trying to track down their white West Indian ancestors because he transcribed many deteriorating records, and he outlined family trees for some of Antigua’s prominent planter families. Although the churches of the British-owned Caribbean islands recorded the births, marriages and deaths of their parishioners, many of these original documents succumbed to dampness, insects, rodents, fires, hurricanes and earthquakes.

Oliver must have had difficulty reading the documents he found, and some records must have been missing, resulting in gaps in the Elmes family tree. The tree does not meet today’s high standards of genealogical proof but, despite these flaws, I am extremely lucky to have these records.

My Ancestor Settled in the British West Indies, a guide to sources for family historians written by John Titford and published by the Society of Genealogists Enterprises Ltd, London, 2011, can help you track down your ancestors in the British West Indies. It gives brief histories of the islands and lists books, websites and record repositories in the Caribbean and the U.K. If your local family history society library does not have a copy, you can order one from www.globalgenealogy.com.