When Stanley Bagg and his business partners began excavating a canal around the Lachine Rapids near Montreal in 1821, they had to deal with more rock and water than they had bargained for.

The Lachine Rapids are a short stretch of white water and submerged rocks in the St. Lawrence River that impede shipping between the port of Montreal and the Great Lakes. According to the legislation that authorized the project, the 14.5-kilometre canal was to be five feet (1.5 metres) deep. On the surface, it was to be forty feet (12 metres) wide so that the long, narrow Durham boats that transported goods and passengers on the river could pass each other. There was to be a towpath beside the water so horses could pull the boats, since it would be impractical to use sails.

The locks were the most impressive part of the project. There was a regulating lock near the canal’s entrance at Lake St. Louis (a broad stretch of the river upstream from the rapids) to allow water into the canal. The other six locks between Lachine and the port raised and lowered boats a total of 13.7 metres. This was nothing compared with the 560-kilometre long Erie Canal, or the Welland Canal with its 90-metre drop over 42 kilometres, but what set the Lachine Canal apart was the fact that all the locks were built of stone, rather than wood, 1.8 metres thick and sealed to prevent leaks. “Nowhere else in North America, or even Britain (with one exception) had locks as large and as solidly built as those on the Lachine ever been constructed,”1 historian Gerald Tulchinksy wrote.

The main contractors, Thomas Phillips, Andrew White, Oliver Wait and Stanley Bagg, were responsible for excavating the canal. Their contract included building the locks and constructing two impressive stone bridges and numerous wooden footbridges so the farmers whose land was crossed by the canal could reach their fields. They had a separate contract to build fences which were supposed to keep grazing cows from damaging the canal banks and workers from scavenging firewood in the nearby farmers’ orchards.

The contractors subcontracted some of the work. For the rest, they hired masons, carpenters, foremen and hundreds of day labourers equipped with picks and shovels, the majority of whom were recent immigrants from Ireland. Horses helped with the heavy hauling.

As treasurer, Stanley Bagg recorded the employees’ pay and kept the account books that listed purchases such as timber and tools.

The canal was designed by Thomas Burnett, a British engineer who had canal building experience in England, but who died before this project was finished. The ten commissioners who had been named by the government to oversee the project visited the work site frequently and met with project leader Phillips whenever problems arose.

Spring flooding was the first major problem the contractors encountered, and it delayed the start of the construction season year after year. The water came mainly from the St. Lawrence River. (This is not an issue today because a dam near Cornwall, Ontario regulates the water level.) In addition, runoff from snow on the Island of Montreal collected in the low, swampy area near the canal’s route. This meant work usually could not start until July, and generally wrapped up around October.

Although some work went on in winter, progress was difficult once the ground was frozen. Soon after they started digging, the contractors discovered a huge area of hard, igneous rock that had to be blasted to make way for the canal, but the men the contractors had engaged to supply gunpowder (one of whom was Stanley Bagg’s brother, Abner,) had difficulty getting hold of it. On October 24, 1822, Abner wrote, “I have just had a most terrible letter from them [the contractors] on the subject, in which they say that no less than 400 men must stop working this day for want of gunpowder….” 2

The delays worried the commissioners. On May 19, 1823, they formally notified the contractors “of the heavy responsibility to which they will be liable if the construction of the aforesaid [masonry] works be delayed by their default, and therefore that their utmost exertion is required to effect the rock excavation to its full depth along the middle of the canal ….” 3

Another problem arose when they reached the St. Pierre River, also known as the Little River. Normally it was nothing more than a small stream, but it turned into a torrent in the spring of 1824, washing away part of the newly built canal embankment. To prevent further damage, the contractors dug a basin to accumulate some of the spring runoff and they built a tunnel for the St. Pierre to run beneath the canal.

All these difficulties were unexpected, and costs skyrocketed. The initial estimate was 78,000 pounds; the final cost came to 107,000 pounds. When the money ran low in 1823 and the government balked at spending more, commission chairman John Richardson arranged a loan from the Bank of Montreal. Eventually, the government funding came through, but the uncertainty must have been of special concern to Bagg, the man who paid the bills.

Part way through the project, the commissioners persuaded the government to approve a shorter and less expensive route. The commissioners decided that the bid from Bagg and his partners for the new section of the canal and a wharf was too high, so someone else did that work.

By August 1824, 11 kilometres of the canal were finished and the waterway opened to commercial navigation as far as the fourth lock. Other builders continued working on the project into 1826, but as far as Bagg and his partners were concerned, the contract was essentially complete in 1825.

This must have been an intense period of Bagg’s life, with dawn to dusk activity during the construction season and year-round worries. He lived near Lachine in the summers since his own house was on Saint Lawrence Street, far from the work site. Furthermore, his task as treasurer must have been challenging: this was the first time such a large civilian project, with so many employees, had been undertaken in Canada.

Meanwhile, ever the entrepreneur looking for additional ways to make money, Bagg also owned a store in Lachine where employees could buy beer, rum and a few groceries. He and several partners also owned a bakery that provided bread to the workers. In addition, the contractors provided bunkhouse accommodations in Lachine for some of the day labourers.

In the end, this massive undertaking was a success. “The competence of the engineer, foremen, labourers and skilled hands in building a substantial canal is attested by the fact that it lasted more than twenty years,” observed Tulchinsky. “No major repairs or alterations were necessary and the Lachine Canal proved adequate for handling the growing volume of traffic to and from the Great Lakes region.”4 It carried thousands of new immigrants toward the interior of the continent, and commodities such as grain, flour, salted pork, ash and timber. In the summer, proud Montrealers took cruises on the canal and strolled along its banks.

Eventually, in the 1840s, a larger canal was built alongside the old one to handle the increased traffic; then the cows and orchards disappeared, and industries grew up along its banks. Stanley Bagg and his colleagues could be proud of their accomplishment, but Bagg never took on another project of this scope, working primarily as a timber merchant for the rest of his life.

Photo credits

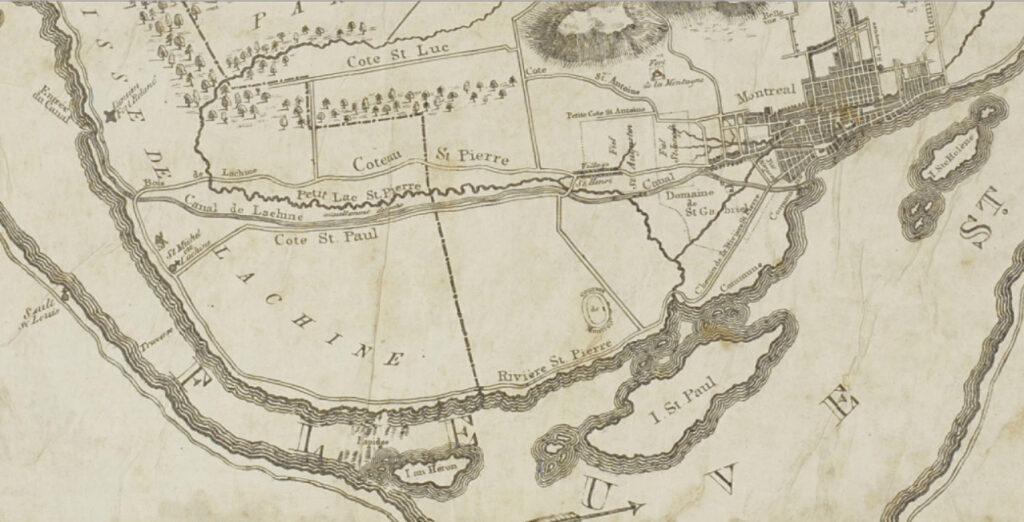

Carte de l’ile de Montreal, Jobin, 1834, BAnQ, https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/2243990

Sources

- Gerald Tulchinsky,“The Construction of the First Lachine Canal, 1815-1826” thesis, 1960, McGill University Department of History, Montreal, p. 77. http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/obj/thesescanada/vol2/QMM/TC-QMM-112940.pdf

- “Abner Bagg Letterbook, Oct 1821-Sept 1825” P070/A5,1, Bagg Family Fonds, McCord Museum, Montreal.

- “Lachine Canal Commission,1821-1842”, Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa.

- Tulchinsky. ibid. p. 109.

Notes

For the background to this story, see the previous post: Janice Hamilton, Writing Up the Ancestors, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2015/02/stanley-bagg-and-lachine-canal-part-1_27.html

Once again, I am indebted to historian Gerald Tulchinsky for his master’s thesis on the construction of the canal. He later wrote a book called The River Barons: Montreal businessmen and the growth of industry and transportation, 1837-53, University of Toronto Press, 1977.

Today, the Lachine Canal is a popular spot for walking, bicycling and recreational boating, and many of the former industrial buildings along its banks have been converted to condos. For more information, see Parks Canada’s website about the Lachine Canal National Historic Site, http://www.pc.gc.ca/eng/lhn-nhs/qc/canallachine/natcul.aspx. There is another interesting and well-illustrated article about the canal at http://www.ameriquefrancaise.org/en/article-685/The_Lachine_Canal_and_its_Industrial_Corridor.html. This subject may be of special interest to people whose ancestors found employment on the canal, or in the nearby factories.

In my next post, I will describe the jobs Stanley Bagg (my three-times great-grandfather) did for the British army with his frequent business partner Oliver Wait prior to obtaining the canal contract.