The old house at the corner of Sherbrooke Street West and Cote des Neiges in downtown Montreal pops up regularly on the internet sites devoted to historical photos of the city, but often the information that accompanies those photos is incorrect. Frequently, people erroneously identify the owner as Montreal landowner Stanley Clark Bagg (1820-1873). In fact, the house belonged to his son, Robert Stanley Clark Bagg (1848-1912).

The building is prominently located on the corner of Sherbrooke Street West and Côte-des-Neiges, which leads up the hill toward Mount Royal. Thousands of people pass by daily, and it is hard not to notice the four-story red sandstone building with its pink tiled top floor.

It has gone through several reincarnations over the years. When it was built in 1891, it formed the south-west anchor of the Golden Square Mile, the neighbourhood where Canada’s wealthiest businessmen, manufacturers and bankers lived. Today it is a commercial building, across the street from other small businesses and medical offices.

The original owner, R. Stanley Bagg (I will refer to him as RSB), grew up in a house called Fairmount Villa that was at the corner of Sherbrooke Street West and Saint-Urbain. His father, Stanley Clark Bagg (SCB), was one of the largest landowners on the Island of Montreal, having inherited several adjoining farm properties along St. Laurent Boulevard from his grandfather, John Clark.

RSB studied law at McGill University and went abroad to continue his studies after graduation, but when his father died of typhoid in 1873, RSB came home. He practiced law in Montreal for a short time, but quit to manage the properties belonging to his father’s estate, a position he held until 1901. He married Clara Smithers (1861-1946) in 1882, and for several years the couple lived just around the corner from Fairmount Villa, where RSB’s mother still resided. Eventually they decided to build a new house in a more fashionable part of the city. When they moved, they had two daughters, Evelyn (1883-1970) and Gwendolyn (1886-1963)—my future grandmother. Their only son, Harold Stanley Fortescue Bagg (1895-1945), was born a few years after the move.

Many houses in Montreal were built of locally quarried grey limestone because it was abundant and cheap, but RSB chose red sandstone, probably imported from Scotland. Originally designed by architect William McLea Walbank, the house was renovated twice in the eleven years RSB lived there, with a major addition constructed in 1902 and other changes in 1906.

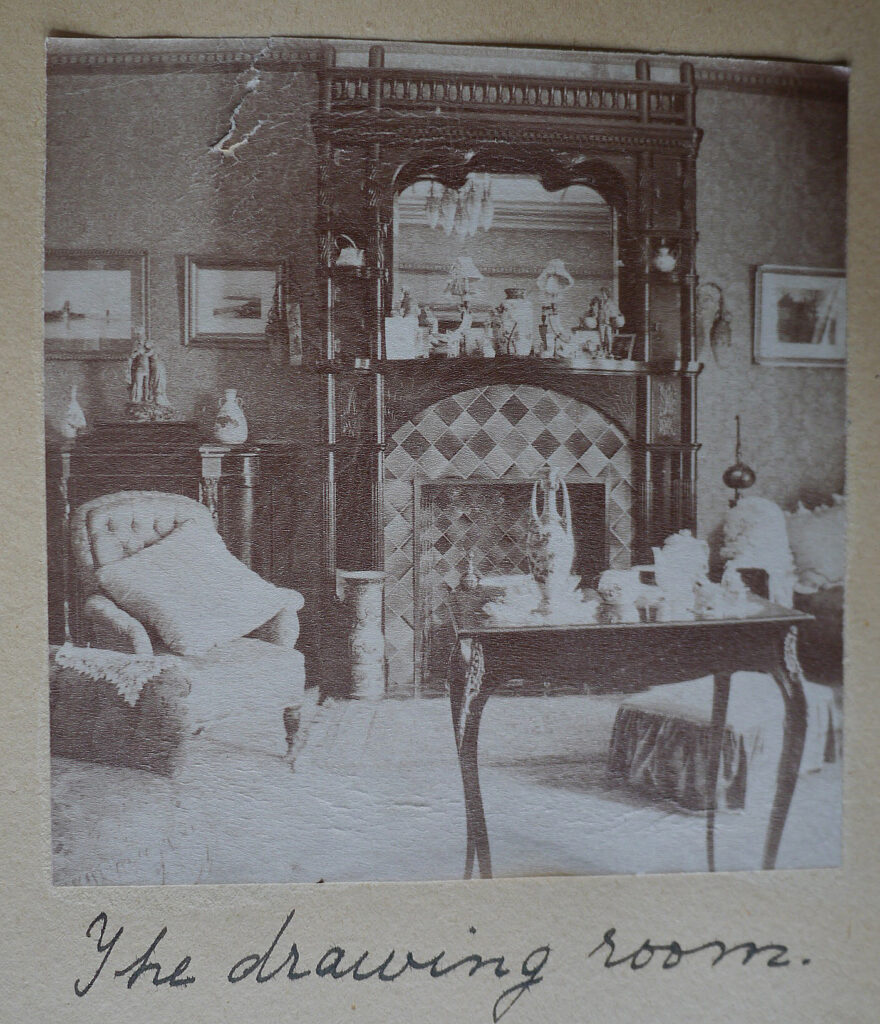

It was a large house, even for a family of five, but the Baggs employed at least two live-in domestic servants—a cook and a maid—and perhaps a man to do the heavier chores. The interior was ornately furnished, as shown in photos my grandmother took of the drawing room, with a carved mantlepiece over the fireplace, heavy floor-to-ceiling drapes, and pillows and knickknacks everywhere. She also took photos of the interior of the tower on the Côte-des-Neiges side of the building. It must have been a sunny spot for reading and a good place to watch people struggle up the hill during a snowstorm.

RSB died of cancer while on vacation in Kennebunkport, Maine in 1912. Clara (who was usually identified as Mrs. Stanley Bagg) divided the house into two apartments and continued to live there until her death at age 85, in 1946.

After she died the house was sold and renovated, with a new entrance facing Côte-des- Neiges, and Barclay’s Bank (Canada) moved in. Many of Montreal’s elite families became customers of this British-based institution. In 1956 the Imperial Bank of Canada took over Barclay’s (Canada) and five years later, it became the Canadian Imperial Bank of Canada (CIBC). In 1979 CIBC decided it could no longer upgrade the old Bagg building to the modern requirements of banking and it moved its customers to a branch down the street at the Ritz Carlton Hotel.

For the next few years, the building was home to a jazz bar on the main floor and a bookstore upstairs, until a fire destroyed the interior in 1982. It may have been that fire that destroyed the cone-shaped roof of the tower. Many years earlier, my mother noticed that a stained-glass window displaying the Bagg family crest had disappeared.

The building was restored in 1985-86 and two art galleries moved in, but the interior featured bare brick walls, a style that was popular at the time in some older parts of the city, but was not appropriate for this Edwardian-era building. An oriental carpet store rented the main floor in the mid-1990s.

Today, Adrenaline Montreal Body Piercing and Tattoos has been located there for many years. I suspect my great-grandparents would not be impressed.

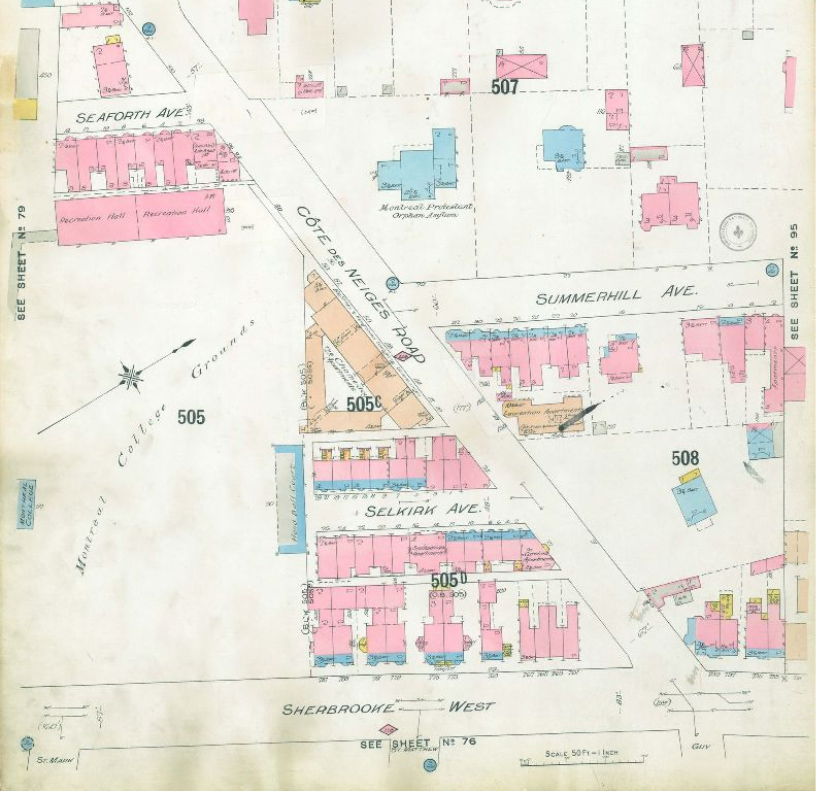

Note: Lovell’s Directory of Montreal shows the address of this building changed several times over the years. It was at 1129 Sherbrooke in 1894-97, and 739 Sherbrooke W. in 1908-1910. The attached house, on the right, had a separate address – 737 Sherbrooke West—and belonged to another family. The Bagg house had been divided into apartments 1 and 2 at 739 Sherbrooke W. by 1927-28, and the address had changed to 1541 Sherbrooke W. apartments 1 and 2 by 1935-36.

This post also appears on the collaborative blog https://genealogyensemble.com

Sources:

Edgar Andrew Collard, “A sandstone house on Sherbrooke St.”, The Gazette, October 20, 1984. (There are several errors about the family history in that article.)

Répertoire d’architecture traditionnelle sur le territoire de la communauté urbaine de Montréal. Les residences. Communauté urbaine de Montréal, Service de la planification du territoire, 1987.

Charles Lazarus, “Farewell to Landmark”, The Montreal Star, April 30, 1979.