Among the male ancestors on my father’s side of the family were many farmers, several doctors, two carpenters, a weaver, a tailor and two botanist-explorers. These were brothers Thomas Drummond (1793-1835) and James Drummond (1787-1863), and both are remembered today through the plants that carry their names. Thomas studied plants in Scotland, western Canada and the southern United States while James immigrated with his family to western Australia and collected plants there.

Thomas Drummond, baptized on 8 April, 17931 at Inverarity Parish Church, near Forfar in eastern Scotland, was one of four children born to Thomas Drummond and Elizabeth Nicoll. Besides brother James, there were two girls: Euphemia, and Margaret, my four-times great-grandmother who married David Forrester and came to Canada in 1833.

Thomas and James no doubt first learned how to identify plants from their father, who was the head gardener of an estate named Fotheringham, near Forfar.

At age 20, Thomas became manager of the nursery and botanic garden at Doohillock which had belonged to the retired director of the Royal Botanic Garden in Edinburgh. During the 10 years he worked there, he became an expert on the mosses of Scotland. He also became acquainted with botanist William Hooker, who eventually became director of the Royal Botanic Garden at Kew, in London.

In 1820, Thomas married Isobel Mungo2 and the couple eventually had three children, Ann, James and Isabella, however, a quiet family life did not suit him. This was a period when Europeans were exploring the far-flung corners of the world and learning all about the plants and animals they found there. Many of these explorers were Scots, such as David Douglas, after whom the Douglas fir tree is named. Their job was to describe these plants in their natural habitats, identify their key features and bring home specimens and seeds.

On Hooker’s recommendation, Thomas was hired as assistant naturalist on Captain John Franklin’s second expedition to the Arctic in 1825. Rather than following the main party to the Arctic, Thomas headed west with a Hudson’s Bay Company party. In the account he wrote of his journey to the Rocky Mountains on horseback and by boat along the Saskatchewan River, he described some of the birds and animals he encountered. They included blue-beaked Ruddy Ducks, a species of flycatcher that courageously attacked larger birds, and packs of impudent Prairie Dogs.

Thomas also explained how he gathered plants. “When the boats stopped to breakfast, I immediately went on shore with my vasculum, proceeding along the banks of the river and making short excursions into the interior, taking care to join the boats, if possible, at their encampment for the night. After supper, I commenced laying down the plants gathered in the day’s excursion, changed and dried the papers of those collected previously; which operation generally occupied me until daybreak, when the boats started. I then went on board and slept until the breakfast hour, when I landed and proceeded as before. Thus I continued daily until we reached Edmonton House, a distance of about 400 miles, the vegetation having preserved much the same character all the way.”3

Thomas spent the winter alone on the shores of the Athabasca River, sheltered by a spruce-bough hut. He rejoined the brigade the next summer and spent the winter of 1826-27 at Edmonton House, where he was nearly killed by a grizzly bear. He nearly died a second time as he attempted to rejoin the Franklin group: a gale blew the small boat he was aboard far into Hudson Bay.

In October 1827, he finally arrived back in England, having succeeded in collecting hundreds of plants, birds and small animals during his travels. The following year, he was appointed curator of the Belfast Botanic and Horticultural Society’s garden. He returned to Scotland in 1830.

A few years later, Thomas returned to North America to continue his botanical explorations in Texas and Louisiana. There he faced floods, cholera and near-starvation. He died in Havana, Cuba in 1835, survived by his wife and children in Scotland. About a dozen plant species, including the well-known Phlox drummondii, a moss genus and a small mammal, are named after him.

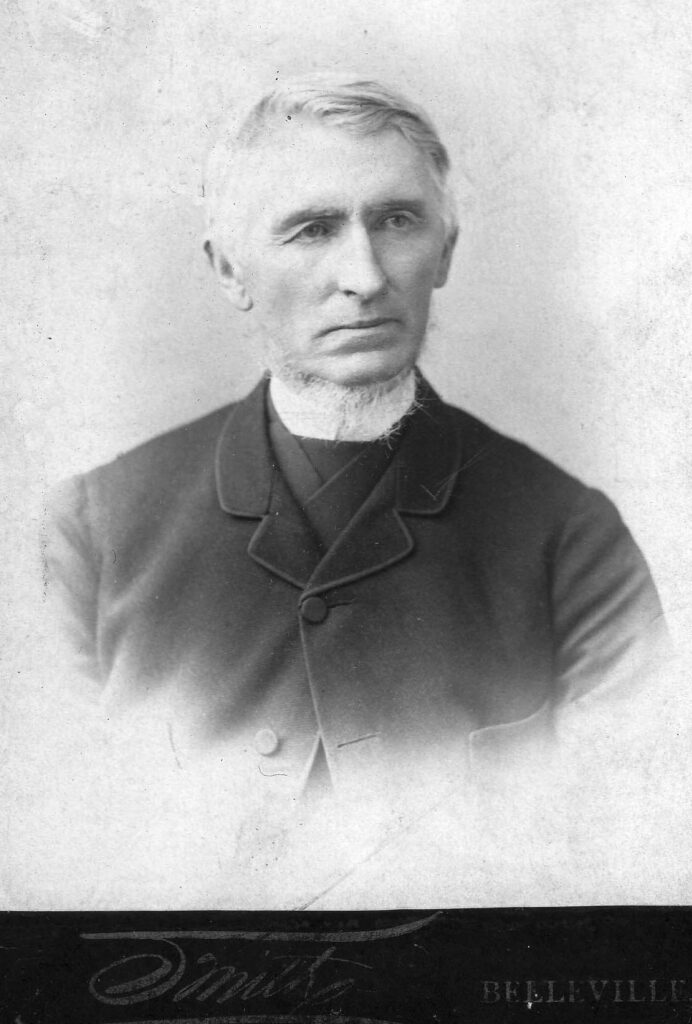

Photo credits: Janice Hamilton

See also:

Janice Hamilton, “Glimpses of a Life,” Writing Up the Ancestors, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2013/10/glimpses-of-life.html

This story has also been posted on https://Genealogyensemble.com

Notes:

I have never been fond of cold, wet weather or long, uncomfortable hikes in the woods, so the discovery that one of my ancestors endured these and many other hardships as a 19th-century botanist and explorer came as quite a surprise. Thomas Drummond has to be one of my most interesting ancestors.

A number of articles have been written about his life, including one in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography (http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/drummond_thomas_6E.html). My favourite, however, is “Drummond of Forfar” by Louise H.R. Meikle, Thomas’s three-times great-granddaughter. It was published in The Scots Magazine, April 2005. A portrait of Thomas Drummond can be seen at http://images.kew.org/thomas_drummond/print/4232976.html.

It is interesting to note that many articles give Thomas Drummond’s birth date as approximately 1790. Genealogy has been able to contribute to our knowledge about him by providing more precisely the dates of his baptism and marriage. We have to rely on letters written by his contemporaries regarding his death, although the exact date does not seem to have been recorded.

An article at http://www.forfarbotanists.org/thomas_drummond_detail.pdf lists many of the plants Thomas discovered. It is on the website of the Friends of the Forfar Botanists (http://www.forfarbotanists.org), an organization that has created a garden in memory of the Drummond brothers and several other local horticulturists.

Another Scottish organization that recognizes the Drummond brothers’ accomplishments is the Scottish Plant Hunters Garden in Pitlochry, Perthshire. (http://www.explorersgarden.com). Visitors to this lovely garden can see species of plants brought to England and Scotland by 19th century Scottish-born botanists such as David Douglas, David Lyall and Archibald Menzies.

Sources:

- “Scotland, Births and Baptisms, 1564-1950,” Database, FamilySearch(https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:XYJZ-DBX : accessed 16 June 2015), Thomas Drummond, 08 Apr 1793; citing INVERARITY AND METHY,ANGUS,SCOTLAND, reference ; FHL microfilm 993,436.

- “Scotland, Marriages, 1561-1910,” Database, FamilySearch(https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:XTVL-QJS : accessed 16 June 2015), Thomas Drummond and Isobel Mungo, 18 Nov 1820; citing Forfar,Angus,Scotland, reference ; FHL microfilm 993,432.

- Drummond, Thomas, “Sketch of a Journey to the Rocky Mountains and to the Columbia River in North America”, Botanical miscellany, Volume 1, edited by Sir William Jackson Hooker, London: John Murray, Albemarle-Street, 1830, p. 183. https://books.google.ca/books?id=8LkWAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA95dq=Thomas+Drummond+sketch+of+a+journey+Hooker+Botanical+miscellany&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0CCEQ6AEwAWoVChMI3eblpMqUxgIVSM2ACh10DgBc#v=onepage&q=Thomas%20Drummond%20sketch%20of%20a%20journey%20Hooker%20Botanical%20miscellany&f=false