Introduction:

In 2015, I wrote a blog post clarifying and correcting the article about my great-great-grandfather Stanley Clark Bagg (1820-1873) that appears in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography (DCB). (See “Don’t Believe Everything You Read About Stanley Clark Bagg,” Writing Up the Ancestors, Dec. 2 2015, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/?p=127) Since then, the DCB has corrected the online version of this biography. (See “Stanley Clark Bagg,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography,http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bagg_stanley_clark_10E.html)

Over the coming weeks, I plan to post a series of stories about Stanley Clark Bagg, expanding on aspects of his life such as his interest in coins and antiquities, his career as a notary and landowner, and his love of travel. In these articles, I refer to Stanley Clark Bagg as SCB to differentiate him from his father, Stanley Bagg (1788-1853,) and from his son, Robert Stanley Bagg (1844-1912).

Most young people spend a long time deciding what they want to be when they grow up. The career of Stanley Clark Bagg (SCB), however, was determined long before he was born.

SCB was destined to become a large landowner on the Island in Montreal, thanks to the foresight of his grandfather. John Clark, a butcher, had immigrated to Canada in the late 1790s and purchased several adjoining farms along the west side of Saint Lawrence Street, the road that led out of the old city gates and past Mount Royal to the north shore of the Island of Montreal. Clark also had property in Durham, England, where he originated.

When Clark died in 1827, he left some of property to his daughter, Mary Ann (Clark) Bagg, but he left most of his estate to SCB, his only grandchild.1 SCB was just seven years old when Clark died, and everyone knew that he would one day be an important landowner. He spent his youth preparing for his future responsibilities as a landlord and a gentleman. For many people whose ancestors had settled in Canada, or who had themselves immigrated to North America in the 19th century, owning land was their greatest dream, so property brought social status, as well as having monetary value. SCB was set for life.

Unfortunately, being a landowner wasn’t what he really wanted to do. According to grandson Stanley Bagg Lindsay, SCB wanted to be an Anglican minister. “SCB was a very religious man and I understand would have entered the ministry, but for the fact that would have entailed leaving Montreal, where there was no theological college, and going to Lennoxville, where theology could be studied at the University of Bishops College. With all his property interests in Montreal and getting married in 1844, it was not possible to be away from Montreal for so long.”2

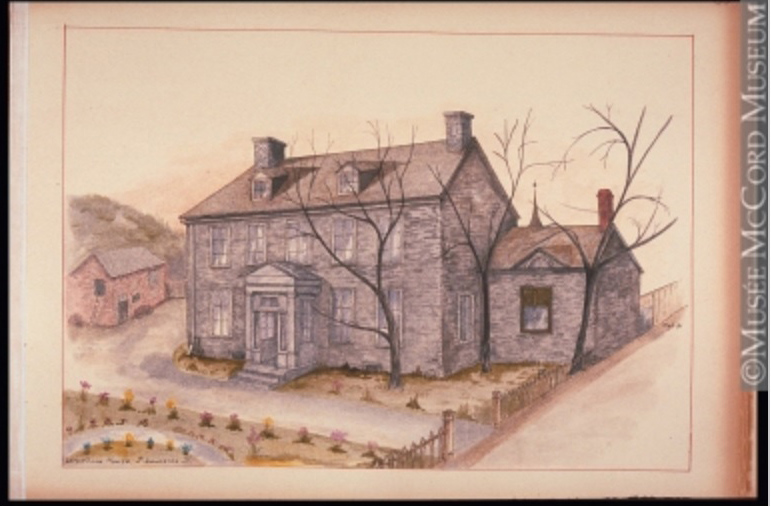

Fortunately, SCB would have the means and the time to read, write (including articles, poetry and hymns,) travel, engage in hobbies and support philanthropic organizations. Stanley Clark Bagg was born on Dec. 23, 1820, the son of American-born merchant Stanley Bagg and his English-born wife, Mary Ann Clark (1795-1835.)3 He grew up at Durham House on St. Lawrence Street, just outside of what was then the small city of Montreal.

SCB probably grew up playing in his father’s orchard and learning to ride a horse – a necessary skill in those days. He was educated by an Anglican minister and later studied at McGill, then just a small college. A hired farm hand would have looked after the cows, chickens and other animals at Durham House, but perhaps SCB was also required to do some farm chores.

On Feb 10, 1835, when SCB was 14, his mother died. His father never remarried, although he probably hired a housekeeper to cook and help look after young Stanley. Soon after Mary Ann’s death, Stanley senior met with a group of friends and relatives in front of a judge to choose a tutor, or guardian, for the boy. Stanley was named his son’s tutor and Gabriel Roy, husband of Stanley’s sister Sophia, became sub-tutor.4 Stanley also acted as executor of both John Clark’s and Mary Ann’s wills, so he managed the properties and SCB’s funds until his son turned 21.

Two years after Mary Ann’s death, Lower Canada faced a serious crisis as some moderate French Canadian nationalists and members of a more radical group known as the Patriotes took up arms in a rebellion. Their main demand was for more responsible government. Troops from the regular British army, joined by members of the local volunteer militia, prepared to defend the status quo.

SCB’s father was a major in the 1st Batallion Loyal Montreal Volunteers5 and SCB served as a standard-bearer at the Battle of St. Eustache.6 About two weeks before his 17thbirthday, SCB witnessed the bloodiest battle of the rebellion in the village of Saint-Eustache, northwest of Montreal. Fought in December 1837, this battle resulted in the deaths of 100 rebels, and many buildings in the area were destroyed by fire.

What SCB thought about these events has not been recorded, but he continued to participate in the militia for more than 20 years, going on inactive status in 1859 with the rank of captain.7

At about age 16, SCB started to train to be a notary, probably following the advice of his father or other influential adults in his life. Notaries played an important role in Quebec society, recording people’s wills, marriage contracts, business agreements, disputes (especially when money was owed) and, most important for SCB, property deeds and rentals. As a notary, SCB would be familiar with the laws pertaining to property transfers.

He served a four-year apprenticeship with notary W.S. Hunter and, in August 1841, his father indentured him for a final eight months to N.B. Doucet, a well-known Montreal notary.8 Doucet undertook to instruct him, give him access to books and render him fit to serve as a notary, while SCB undertook to apply himself. By the spring of 1842, he was a notary.9

SCB finished his apprenticeship a few months after he turned 21. As an adult, he could now manage his inheritance, collecting the rent for the farms he owned and buying and selling properties. Perhaps he also started to think about marriage. First, though, he and his father went on a trip to England to wind up some business.

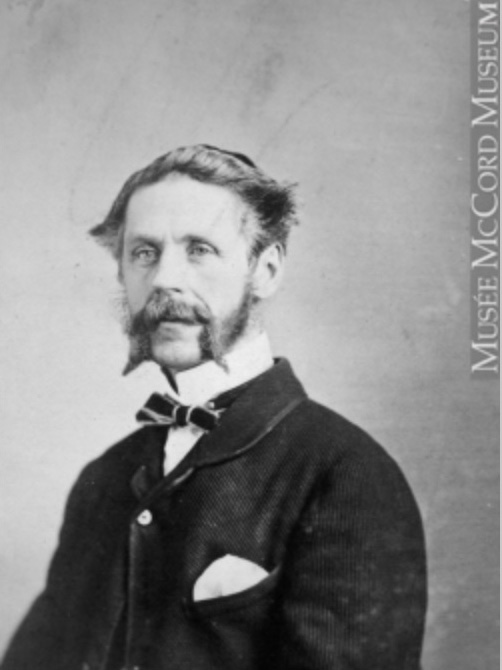

Photo Credit: Photo of Stanley Clark Bagg, 1863, by William Notman, copyright McCord Museum

See also:

Janice Hamilton, “John Clark, 19th Century Real Estate Visionary” Writing Up the Ancestors, May 22, 2019, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/?p=52

“A Home Well Lived In” Writing Up the Ancestors, Jan. 21, 2014, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/?p=181

Mary Ann (Clark) Bagg, Writing Up the Ancestors, Nov. 29, 2013, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/?p=187

The Life and Times of Stanley Bagg, Writing Up the Ancestors, Oct. 5, 2016 https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/?p=108

Sources:

- Henry Griffin, notarial act #5989, “Last Will and Testament of Mr. John Clark of Montreal,” 29 August 1825, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (BAnQ); and George Dorland Arnoldi, notarial act # 3842, “Last Will and Testament of Mrs. Mary Ann Clark, wife of Stanley Bagg,” 10 December 1834, BAnQ

- Unsigned, undated (probably Stanley Bagg Lindsay), “Stanley Clark Bagg,” Lindsay family collection.

- Stanley Clark Bagg, born Dec. 22, 1820; baptized Christ Church Cathedral, Montreal, July 2, 1822. Institut Généalogique Drouin; Montreal, Quebec, Canada; Drouin Collection; Author: Gabriel Drouin, comp.,Quebec, Canada, Vital and Church Records (Drouin Collection), 1621-1968 [database, Ancestry.ca: on-line]. (Accessed 23 Dec. 2019) entry for Stanley Clark Bagg, citing Gabriel Drouin, comp. Drouin Collection. Montreal, Quebec, Canada: Institut Généalogique Drouin.

- Although Lower Canada was a British colony at the time, it retained many legal traditions, including this one, stemming from the French Regime. “Tutorship: minor Stanley Bagg” BAnQ microfilm #1857, Tutelles, 5 Decembre 1834 au 20 Mars 1835, Document 174 – 27 Feb. 1835.

- Elinor Kyte Senior, Redcoats and Patriots: The Rebellions in Lower Canada. 1837-38, p 214, Stittsville, ON: Canada’s Wings, Inc., 1985.

- Pierre B. Landry, “BAGG, STANLEY CLARK,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 24, 2019, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bagg_stanley_clark_10E.html.

To learn more about the role of the militia in the British colony of Lower Canada, see Brian Young, “The Volunteer Militia in Lower Canada, 1837-1850,” Power, Place and Identity: Studies of Social and Legal Regulation in Quebec, edited by Tamara Myers, Kate Boyer, Mary Anne Poutanen, and Steven Watt, 37–54. Montreal: Montreal History Group, 1998. http://web.archive.org/web/20041107171328/http://www.ghm-mhg.mcgill.ca/publications/ppi/young.html - “List of Officers of the Sedentary militia of Lower Canada, 1862,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.ca: accessed Dec. 23, 2019), entry for Stanley C. Bagg, citing List of Officers of the Sedentary militia of Lower Canada, 1862, Quebec: S. Derbyshire and G. Desbarats, 1863.

- Joseph-Hilarion Jobin, “Indenture of Stanley C. Bagg to N.B. Doucet,” notarial act #2977, 23 Aug 1841, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec; abstract by Sherry Olson.

- Library and Archives Canada, The Canada Gazette, database, (entry for Stanley Clark Bagg; accessed Jan. 7, 2020). citing The Canada Gazette, no. 37, Published by Authority, Kingston, June 11, 1842, p. 326. http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/databases/canada-gazette/093/001060-119.01-e.php?image_id_nbr=945&document_id_nbr=1699&f=p&PHPSESSID=j1au0sblq8sejaol266jar2vp4