A portrait of my four-times great-grandmother Mary Mitcheson shows a plain but pleasant looking woman with dark eyes, rosy cheeks and a frilly cap. The wife of Montreal butcher and landowner John Clark, she held a book in her hand and had rings on her fingers that suggest a certain level of refinement.

Mary was born at Stowe House, in the tiny village of Cornsay, County Durham, in northeast England, to Joseph Mitchinson (an earlier spelling of the family name) and his wife, Margaret Phillipson. She was baptized in 1776 at Whickham parish church, her mother’s parish. Mary had five younger siblings: Robert (born in 1779), Margaret (1781), William (1783), Elizabeth (1785) and Jane (1793).

On June 10, 1794, Mary Mitchinson, age 21 (or so she said,) of Lanchester, married John Clark at St Giles parish church, on the outskirts of the city of Durham. The following year, she gave birth to a daughter. Mary Ann Clark was baptized in Lanchester, the rural parish in which Mary’s father had grown up.

At some point over the next few years, Mary, John and their little girl left England. The first evidence I have found of their presence in Montreal is a deed showing they had purchased a property on de La Gauchetière Street in 1799. A few years later, Mary gave birth to a son, John F. Clark. He died in June 1806, aged eight months.

Mary may have enjoyed a level of financial independence unusual for a woman at that time. When she turned 21, she inherited 50 pounds from her grandfather. When her father died in 1821, he left her 100 pounds, specifying in his will that it was for her use alone; usually a woman’s property automatically became her husband’s. And when they sold the de La Gauchetière property in 1810, both John Clark and Mary Mitcheson signed the deed of sale, so perhaps they were co-owners of the property.

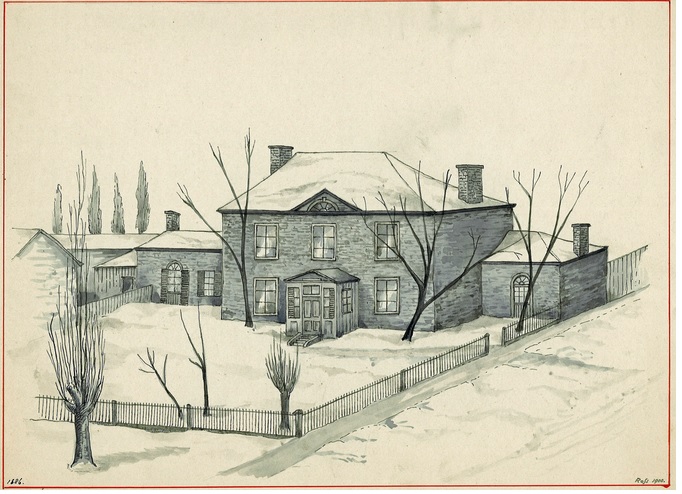

In 1819, daughter Mary Ann married Stanley Bagg, an American-born merchant who had rented an inn known as the Mile End Tavern from John Clark. The following year, the Clarks’ only grandchild, Stanley Clark Bagg, was born. By this time, the young Bagg family was living at Durham House, on St. Lawrence Street, while the Clark couple lived up the road at Mile End Lodge.

John Clark died in 1827, at age 60. He left Mile End Lodge and another property, the Clark Cottage Farm, which was further north on St. Lawrence Street, to Mary. He willed his other properties to his daughter and to his young grandson. A clause in his will ensured that Mary Ann would give her mother 1,000 bundles of good timothy hay every year. Perhaps Mary continued to raise some cattle and needed the hay to feed them over the winter.

But Mary must have found Mile End Lodge too big, so about a year after John’s death, she moved to a smaller house known as Clark Cottage or Mitcheson Cottage. It can still be identified today at the northwest corner of Bagg Street and Clark Street in Montreal’s Plateau district.

As a widow for almost 30 years, Mary seems to have been active in running her properties. In 1844, Stanley Clark Bagg, by then a notary, looked after a lease for his grandmother and, on at least one occasion, she placed a rental notice in the local newspaper for Mile End Lodge.

Mary Ann died in 1835, Stanley in 1853. Mary outlived them both, dying on January 15, 1856, age 80. She is buried with her husband, daughter, son-in-law, grandson and other family members in the Bagg family mausoleum at Mount Royal Cemetery.

Edited May 29, 2014 to correct Mary’s place of residence at the time of her marriage.

Photo credits: Mary Mitcheson Clark, private collection

Mile End Lodge, painting by John Hugh Ross, copyright Stewart Museum.

Edited June 3, 2014 to correct date of marriage.

Research remarks: Regular readers of this blog may find the name Mitcheson rings a bell. That is because Mary’s brother Robert immigrated to Philadelphia around 1817. His daughter Catharine Mitcheson married her first cousin once removed, Stanley Clark Bagg, in 1844.

I did a lot of research on the Mitcheson family when I first started doing genealogy five years ago. I found most of the baptism and marriage records on www.familysearch.org, but I had help getting started: a cousin had done some research in the 1970s, and another descendant contacted the vicar of Lanchester parish in 1914. The vicar sent him records for the Mitcheson family going back to the early 1700s, but Mary’s name was not included since she was baptized at Whickham.

There is a note in the Bagg family Bible indicating that Mary was born at Stowe House. I had no idea where that was, but when I hired a local retired genealogist to take us to Lanchester, Whickham and some other parish churches around Durham a few years ago, he took us to Cornsay. We were not sure which house it was, but now I see online that Stow House has been renovated and made into vacation rental cottages.

The following newspaper clipping can be found in the Bagg Fonds at the McCord Museum in Montreal: “Mile End Lodge: two-storey stone house near St. Lawrence Toll Gate, with stable, garden, use of well; within half an hour’s walk of post office; rent moderate. Apply to Mrs. Clark, Mitcheson Cottage, near the premises, or to S.C. Bagg, Fairmount Villa. Feb. 3, 1853.”

Notarial records of deeds, wills, leases and so on can be found at the Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec, https://www.banq.qc.ca. The deed of sale I mentioned in the article was #2876 in the records of notary J.A. Gray, dated 18 October, 1810.

Most Durham wills are kept at the archives of the University of Durham, but I ordered Joseph Mitcheson’s will online from the National Archives in London.