William Mitcheson (1783-1857) is one of my sidebars, but he was the brother of two of my great-great-greats (there was a subsequent marriage between cousins), he built up a thriving business as an anchor smith on the docks of London, and he had a large family, so every once in a while I do a search for his name.

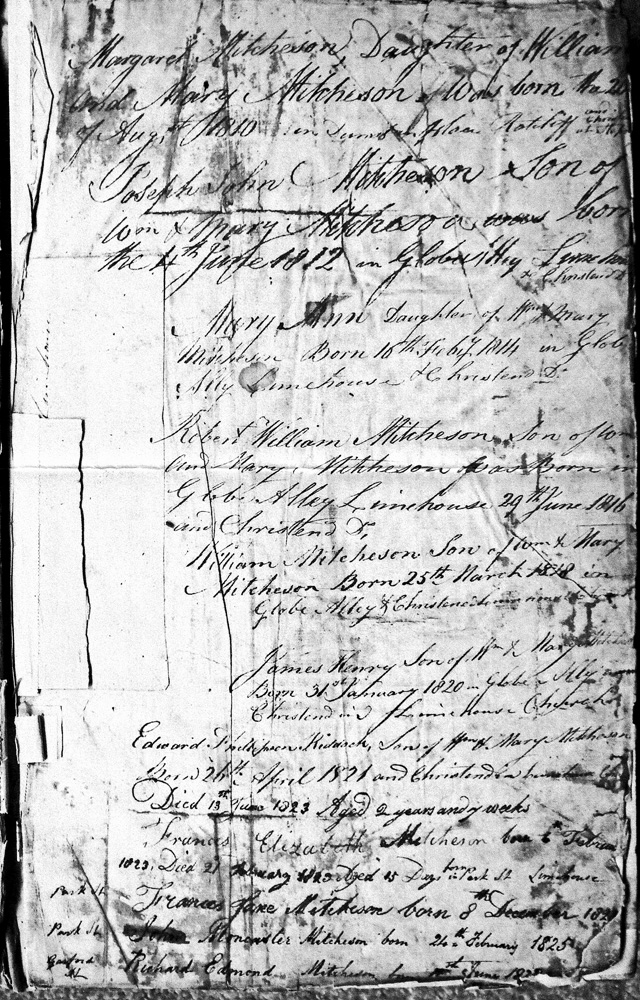

In 2014 I got a hit on a message board: someone had a copy of the family bible of William Mitcheson of Limehouse and was looking for descendants. I responded and learned that this gentleman had inherited the bible from a distant relative.

We agreed this 200-year-old bible would be better off in England than in Canada, so he photocopied the births and deaths recorded in it and sent them to me. That information partly resolved my confusion about William’s eleven children.

Born in Durham

Mitcheson is not a common name, except in the north-east of England where County Durham is located. My ancestors’ name, initially spelled Mitchinson, can be traced to 1727 in Lanchester Parish, northwest of the city of Durham.

William Mitcheson, baptized at Lanchester, 31 Aug. 1783, was the son of Joseph Mitcheson (1746-1821), a small-scale landowner, and Margaret Phillipson (1755-1804), who was from Swalwell in Whickham Parish, Durham.

Joseph and Margaret had six children. The eldest was Mary (1776-1856), who married John Clark and settled in Montreal, Canada. Robert (1779-1859) also left England and settled in Philadelphia, where he married Mary Frances McGregor. The others remained in England. Margaret (1781-1864) married Thomas Dodd. Next came William. Elizabeth (1785- ) married John Maugham, and Jane (1793- ) married David Mainland.

With a good supply of coal in County Durham, there had been an iron manufacturing industry in the area for a century and there was a shipbuilding industry. Perhaps the experience and contacts William developed there allowed him to leave Durham for greater opportunities in London.

William married Mary Moncaster, also a native of County Durham, on 9 Sept. 1809 at St. Anne Parish Church, Limehouse, in east-end London. The couple’s first child, Margaret, was born at nearby Ratcliffe in 1810. Soon after, the family moved to Limehouse, and most of their baptisms and marriages took place at St. Anne’s church in Limehouse.

Limehouse Faced the Thames

Limehouse, on the north bank of the Thames River, has had dockyards for centuries. In the early 1800s, the West India Docks were built nearby, and London’s port was booming. An article about Limehouse Hole on British History Online says, “In the late 1820s William Mitcheson, an anchor-smith, took premises near the Emmett Street corner [of Garford Street]. By 1835 he had built an anchor-works along the western 150 ft of Garford Street with, from west to east, a corner shop, a forge about 50 ft square, a house, an office and warehouses. Mitcheson’s sons remained at what became Nos 1–7 (odd) Garford Street until the early 1860s.”

William Mitcheson’s business, initially focused on anchor making, expanded to include ship chandlery and chain making. Eventually, the family owned a fleet of ships that sailed to North America and beyond. After William and several of his sons died in the late 1850s and early 1860s, the company died too.

The Family Bible

Here are William and Mary’s children according to the Mitcheson family bible, which is now in the hands of the East of London FHS. I have added whatever marriage and death information I could find on Ancestry.

Margaret Mitcheson, b. 20 Aug. 1810; m. Richard Edmund Wicker, 1827; d. 14 May 1870, Middlesex, widow. Joseph John Mitcheson, b. 4 June 1812; d. 1854, Sussex.

Mary Ann Mitcheson, born 16 Feb. 1816; m. Manassah Philip Eady, 5 Oct. 1833; widowed; m. David Mainland, 6 Jan. 1849, master mariner; d. 1887, West Ham, Essex.

Robert William Mitcheson, b. 29 June 1816; m. Sarah Smith, 9 Jan. 1841; d. 11 May, 1859, Middlesex, anchor smith.

William Mitcheson, b. 25 March, 1818; m. Arabella Smith, 9 Jan. 1841; d. 5 Feb. 1863; widower; anchor smith and ship chandler.

James Henry Mitcheson, b. 31 Jan. 1820; m. Sophia Ann Hopkins, 22 Oct. 1847; d. 24 Jan. 1894, Edmonton, Middlesex.

Edward Phillipson Riddoch Mitcheson, b. 26 April 1821; d. 13 June 1823.

Frances Elizabeth Mitcheson, b. 6 Feb. 1823; d. 21 Feb. 1823.

Frances Jane Mitcheson, b. 8 Dec. 1824; m. Thomas Anthony Humble Dodd, surgeon, 1848; d. 19 Aug. 1898, Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

John Moncaster Mitcheson, b. 24 Feb. 1825; d. 22 April 1894, West Ham, Essex.

Richard Edmund Mitcheson, b. 11 June 1828; m. Mary Woods, 1858, West Ham, Essex; d. 22 Nov. 1904.

Research remarks There are several other articles on this blog about Mary Mitcheson Clark and Robert Mitcheson, including https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2014/05/mary-mitcheson-clark.html, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2013/11/philadelphia-and-mitcheson-family.html and https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2013/10/help-from-grave.html.

Ancestry incorrectly says William senior married Mary Worchester; her last name was Moncaster.

I did not find a record of William Mitcheson senior’s death, but I obtained a copy of his will from the National Archives. It was proved 12 March 1857.

Brothers Robert William and William Mitcheson married two sisters, Sarah and Arabella Smith, at a double ceremony in Chippenham, Wiltshire in 1841.

The 1841 census return on William Mitcheson’s family is confusing because the information does not quite fit what I now know about them. It shows five people in the household besides William and Mary Mitcheson. John and Frances, ages rounded off to 15, are clearly their children. There is another 15-year-old listed, Eliza, but I don’t know who she was, nor do I know the identity of George Mitcheson, 25, anchor smith. Richard Edmund, the youngest of the family, was missing. The last person enumerated was Mary Dodd, 25.

I’d like to learn more about the Mitcheson family business and the ships they owned. If any readers can suggest resources, I’d love to hear about them. And if this is a topic that interests you, be sure to visit the Museum of London Docklands, right next to Canary Wharf. Garford Street is just a few streets away from the museum.

Updated clarifications 10/09/2016.