Since I started writing my own blog and contributing to https://www.genealogyensemble.com, I have heard from several relatives I never knew I had. A distant relation in Australia is helping me break through a brick wall in Ireland. A researcher in Vancouver has provided information about a great-great aunt who moved there from Montreal. And a distant cousin in Ontario forwarded some of the letters our newly immigrated Hamilton ancestors sent home to Scotland.

Another breakthrough came through the kindness of the parish archivist in Lesmahagow, Scotland, hometown of those Hamilton ancestors. He ran across the article I posted about my three-times great-great grandfather Robert Hamilton, a tailor in Lesmahagow, near Glasgow. Robert’s son, daughter-in-law and grandchildren left Scotland in 1830 and settled as farmers in what is now Scarborough, a suburb of Toronto. Robert, an elderly widower, stayed behind and died in Lesmahagow two years later.

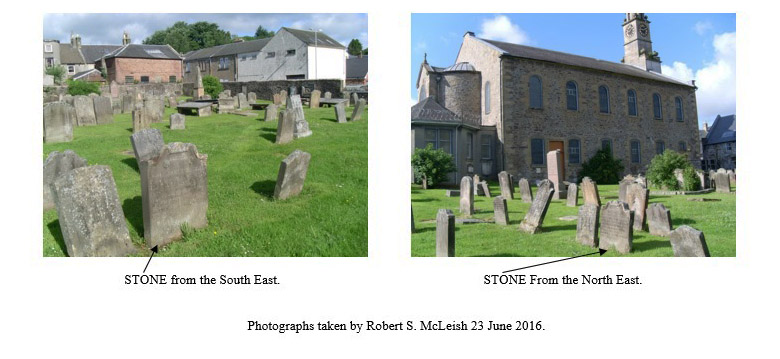

My uncle did some research on the family in the 1950s and copies of the documents he collected eventually made their way into my hands. One of the items I acquired was a sketch of the parish cemetery in Lesmahagow, showing the location of the grave of Robert Hamilton and his wife, Janet Renwick. When my husband and I visited in 2012, we found only grass in that spot, so I was delighted when the parish archivist emailed me a photograph of the missing Hamilton gravestone, taken in 1999.

Someone else then messaged me that the stone was still there, so I again contacted Lesmahagow. The parish archivist there very kindly located the Hamilton family gravestone that I had missed, cleaned it up and rephotographed it. The photo he sent me shows the location of the stone, close to where I thought it was, but far enough away that we missed it. Thank you, Robert.

The text on the stone says: Erected in memory of Robert Hamilton tailor of Abbey Green who died 18th Nov. 1831, aged 77 years, and of Janet Renwick, his spouse, who died 2nd May 1821, aged 63 years, and of their son Archibald, who died in infancy.

Most Scots could not afford gravestones in those days, and I am sure the Hamiltons were no different. Tailors did not make much money. This is a nice big stone, and I suspect it was erected by family members many years later, perhaps with money sent to Scotland from the farm in Canada.

This post was updated Dec. 27, 2016.

See also Janice Hamilton, ” Robert Hamilton, Tailor, of Lesmahagow,” Writing Up the Ancestors, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2013/12/robert-hamilton-tailor-of-lesmahagow.html

Janice Hamilton, “From Lesmahagow to Scarborough” Writing Up the Ancestors, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2013/12/from-lesmahagow-to-scarborough.html