Robert Stobo Jr. is more a phantom ancestor than a brick wall. There does not seem to be a church record of his baptism and apparently he did not marry. He is thought to have died at sea in 1836, so there is no official death record either. Yet there are indications that he not only existed, but that he was a successful timber merchant in Upper Canada. According to “The Stobo Family: Scarborough, 1824 –“ Robert Stobo Jr. was born in Lanarkshire, Scotland on 3 Feb. 1798, the fifth of the nine children of Robert Stobo (1764-1834 ) and Elizabeth Hamilton (c. 1763-1834).1 All the other children’s baptismal records have survived, but Robert’s is nowhere to be found.

The Stobo parents and several of their children, who were by then young adults, immigrated to Scarborough Township, Upper Canada in 1824.2 In subsequent years, many families from Lanarkshire followed them, but the Stobos led the way.3 Six years later, their oldest daughter, Elizabeth, her husband Robert Hamilton and their children stayed with the Stobo family for several months following their arrival in Scarborough.4

Robert Jr. was mentioned in a letter that brother-in-law Robert Hamilton wrote to relatives in Scotland in 1830. Hamilton wrote, “Robert Stobo wished to inform his brother James that he has ? the iron plough that it is doing very well and will be of great use on the farm.”6 (James Stobo, Robert’s older brother, had remained in Scotland.)

As early settlers, the Stobos were able to acquire a prime piece of real estate near the Scarborough Bluffs overlooking Lake Ontario. In 1826, Robert Stobo purchased two neighbouring lots near the water: Concession B Lot 22 and Concession C Lot 22. Robert Stobo purchased another lot from the government, Concession B Lot 21, in 1834.5 (It is not clear whether this was Robert senior or junior.)

Prior to the arrival of these Scottish settlers, Scarborough’s land had never been cleared, and its forests produced immense quantities of square timbers, shingles and firewood. The Stobo farm was near the water, facilitating transportation, and historian David Boyle wrote that Robert Stobo became a prominent timber merchant.7 Given that Robert Sr. was 60 years of age when he immigrated, it was likely the son who went into the timber business.

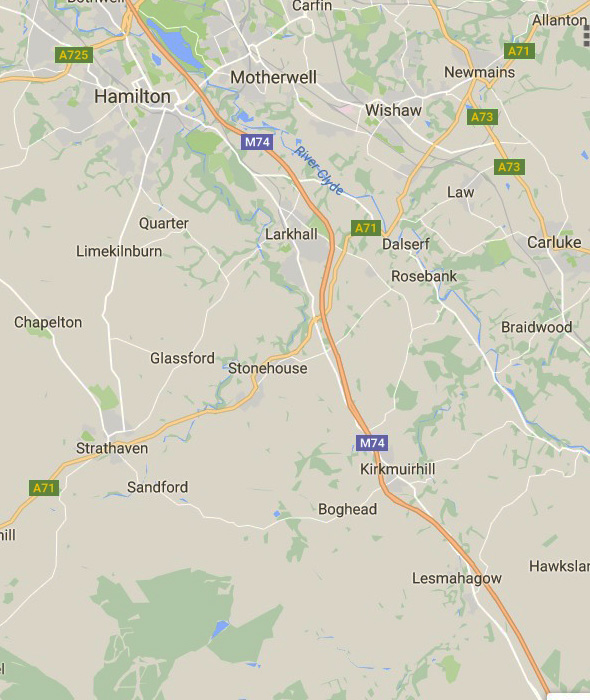

Perhaps it was the timber business that sent Robert Jr. on a trip back to Scotland a few years later. According to a letter dated 9 March, 1836 from William McCowan in Lesmahagow, Lanarkshire to his nephew Robert McCowan in Scarborough, Robert Stobo Jr. was probably lost at sea. He wrote, “Your father had wrote 7 [letters] in which number there was one to him [Hugh Wilson] which was to have come with Stobbo, the fate of whom with ship and all in it has not been heard of.” 8

The parents had both died prior to Robert Jr.’s disappearance. There was a terrible cholera outbreak in Scarborough Township in 18349 and it killed both Robert Sr. and wife within days of each other. He died on 12 Aug. 1834, age 70, and she followed on 15 Aug., age 71.10

Despite the loss of their parents and brother, John Stobo (1811-1889), Jean Stobo Glendinning (1807-1893) and Elizabeth Stobo Hamilton (1790-1853) remained in Scarborough and prospered on the rich farmland. The township remained primarily rural for more than a century and Isaac, son of John Stobo and Frances Chester, is said to have shot the township’s last black bear, in the winter of 1885, on the Scarborough Bluffs, Concession B Lot 210.11 For the most part, I’m proud of my Scarborough ancestors, but this was not a story I wanted to read.

See also:

For a map that shows the location of the Stobo properties, see http://www.mccowan.org/historic.htm

Janice Hamilton, “The Stobos of Lanarkshire,” https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2016/12/the-stobos-of-lanarkshire.html, posted Jan. 12, 2017.

Janice Hamilton, “From Lesmahagow to Scarborough,” https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2013/12/from-lesmahagow-to-scarborough.html, posted Dec. 13, 2013, revised Dec. 27, 2016.

Janice Hamilton, “The Glendinnings of Scarborough,” https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2016/12/the-glendinnings-of-scarborough.html, posted Dec. 16, 2016.

Notes and Sources:

When my husband and I visited Scarborough in the autumn of 2016, I wanted to get as close as possible to the area where the Stobos owned their land. The Stobos’ neighbour, Jonathan Gates, who settled in the area around 1815, owned Gates Tavern on the Kingston Road and there was a ravine between the properties known as Gates Gulley. We walked part of the way down to the lake on a public trail through the ravine, and we stopped at a small neighbourhood park to get a view of the bluffs. Later, we visited the archives of the Scarborough Historical Society, which houses a wealth of information about the community and its early residents.

- “The Stobo Family: Scarborough, 1824 –“ is a family tree manuscript transcribed by descendant Margaret Oke. It can be found in the Ontario Genealogical Society collection housed at the Toronto Reference Library.

- The Stobos had a reference letter from the minister of Stonehouse Parish Church, Lanarkshire that introduced them to their new Presbyterian church community in Canada. Dated 1 Aug., 1824, the letter is transcribed in “The Stobo Family: Scarborough, 1824 –“.

- Barbara Myrvold, The people of Scarborough: A History, Scarborough Public Library Board: 1997, http://www.virtualreferencelibrary.ca/detail.jsp?Entt=RDMDC-238353&R=DC-238353&searchPageType=vrlp.59.

- Letter from Robert Hamilton, Scarborough, May 27, 1830, to his father in Lesmahagow. R.H. Martin Collection. A distant cousin sent me a transcription of a poor photocopy of this letter, which is not to say that I didn’t appreciate it, but to explain why a word is missing.

- This information was provided to me by the Scarborough Historical Society archivist from microfilm of the Ontario land records.

- Robert Hamilton, Ibid.

- David Boyle, editor, The Township of Scarboro, 1796-1896, printed for the Executive Committee by William Briggs, Toronto, 1896. p. 133. https://archive.org/details/townshipofscarbo00boyluoft

- This letter was quoted in a private email to me from D.B. McCowan, 31 Dec. 2013.

- M. Jane Fairburn, Along the Shore: Rediscovering Toronto’s Waterfront Heritage, Toronto: ECW Press, 2013, p. 49, https://books.google.ca/books?id=nT-DAAAAQBAJ&pg=PA44&dq=Township+of+Scarboro&hl=en&sa=X&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=Township%20of%20Scarboro&f=false Also, http://www.mccowan.org/cholera.htm.

- St. Andrews Presbyterian Cemetery (Bendale), Scarborough, Ontario. A genealogical reference listing. Ontario Genealogical Society, Toronto Branch. 1988 and 1993. M.I. #26.11

- Boyle, Ibid, p. 238.