Before 1900, photography was the domain of the expert. Cameras were complicated, film was bulky. That year, the Eastman Kodak company introduced the Brownie camera, a simple box with a lens, loaded with a roll of film, and photography became available and affordable to the general public. My grandmother’s family were early adopters of this new technology, and my grandmother, Gwendolen Bagg (1887-1963), became an enthusiastic photographer.

One of her first subjects was her own house in Montreal’s Golden Square Mile. She photographed not only the exterior, but also the drawing room (living room), with its ornate mantelpiece and heavy drapes.

The majority of photos were taken during summer vacations with her family. Many Montrealers left the city in the summer, not only to escape the heat, but also to avoid the outbreaks of disease that plagued the city in those years. In the early 1900s, the Bagg family went to Cacouna, on the shores of the St. Lawrence River, and they also spent time at a lake near Ste. Agathe, in the Laurentians, north of Montreal.

Gwen photographed her father stretched out on the lawn at Cacouna, her mother in a wide-brimmed hat, and her older sister on horseback and in a canoe. Her little brother, Harold, was a favourite subject. In one picture, taken when he would have about five years old, he posed with his two girl cousins. According to the custom of the day, he had long hair and was dressed exactly like the girls, in what appears to be a dress. The following year, his blonde hair remained long, but Harold wore a sailor suit.

In her late teens, Gwen photographed her friends, wearing elaborate bathing costumes on the beach near Kennebunk, Maine. On the porch at the hotel where they stayed, all the young women wore light dresses that reached the ground and covered their arms to their wrists. They must have been very hot.

In 1913, Gwen photographed her mother, by now a widow and dressed in black, leaning up against a big log at Kennebunk Beach, chatting with a friend. By this time, her sister Evelyn was married, and Gwen liked to photograph her little niece, Clare.

The camera was a good one, and whoever Gwen shared it with (probably her mother), was also a good photographer. All these photos were in focus, well exposed and tightly composed. Most importantly, Gwen put her pictures into albums and identified most of the people, places and years they were taken. She got married in 1916, and after that, although she continued take family photos, the prints ended up in a box, loose and unidentified.

Gwen kept these albums and my mother inherited them and then passed them on to me. Several years ago, I asked the McCord Museum in Montreal whether they would like them. The McCord already had a collection of letters and business ledgers that had belonged to the Bagg family, so these photos shed light on another aspect of their past. The albums are now part of the Bagg Family Fonds, and a few of them have been digitized and can be viewed on the McCord’s website at http://collections.musee-mccord.qc.ca/scripts/explore.php?Lang=1&tableid=18&tablename=fond&elementid=31__true (go to the very bottom of this page).

Notes:

I cannot say for certain that my grandmother had a Brownie, but she certainly had some type of simple box camera. The square photos in her album are approximately 3 ½” x 3 ½”, corresponding to the Kodak film sizes 101 and 106. This chart on the Brownie website describes the different sizes of film that Brownie cameras used over the years: http://www.brownie-camera.com/film.shtml. If she did have a Kodak, it was probably similar to the camera described on this website: http://www.historiccamera.com/cgibin/librarium/pm.cgi?action=display&login=no2bullet

Photo credits:

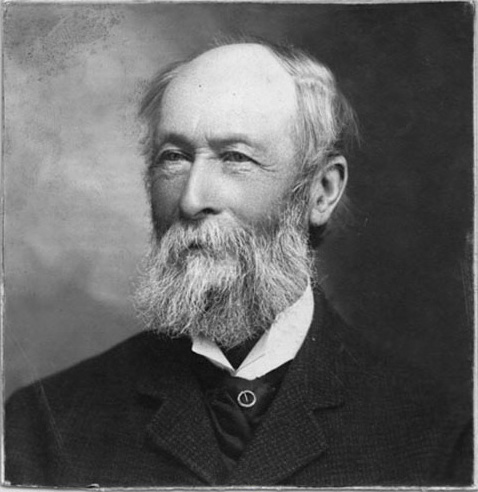

Photo of Gwen Bagg c. 1903, from her photo album, McCord Museum, Bagg Family Fonds, P070

Gwendolyn Bagg, “Harold Bagg, Cacouna, 1903”, McCord Museum, Bagg Family Fonds, P070, http://collections.musee-mccord.qc.ca/en/collection/artefacts/M2013.59.1.62

This article is also published in the collaborative blog https://genealogyensemble.com