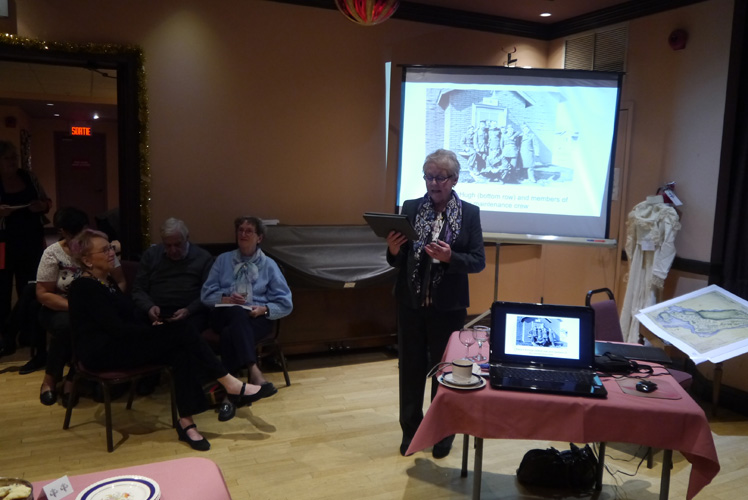

Tonight is the night Beads in a Necklace: Family Stories from Genealogy Ensemble will be launched. I just came back from doing an interview on CBC radio about the book, and tonight all nine authors get together to see it and feel it in our hands for the first time. We have invited family members and friends to join us for this celebration, so tomorrow we’ll post pictures. Meanwhile, here is an look at the cover, and a copy of the media release we prepared.

Beads in a Necklace: Family Stories from Genealogy Ensemble

The nine women who write the family history blog https://genealogyensemble.com have fleshed out the dashes between the dates on their family trees, chosen their favourite stories about their ancestors and published them in a new book called “In Beads in a Necklace: Family Stories from Genealogy Ensemble.”

Inspired by family myths, heirlooms, letters, and vintage photographs, these are historically accurate stories with a huge heart. They describe the lives of merchants and military men, society ladies and filles du roi, reverends, rogues, medical men, restless women, cooks and farmers, each of whom was somehow related to one of the book’s authors.

These ancestors lived between 1650 and 1970 and hail from Montreal, rural Quebec, Ontario, New Brunswick, the United States and other places around the world.

Contributors Lucy Anglin, Barb Angus, Marian Bulford, Claire Lindell, Sandra McHugh, Dorothy Nixon and Mary Sutherland, for the most part amateur authors, developed their creative writing skills over a five-year period under the guidance of professional writers Janice Hamilton and Tracey Arial, who also co-authored and edited the collection.

Getting together monthly, they experimented with a variety of narrative techniques to preserve the ever-fading memories of their great uncles and four-times great-grandparents, and to shed light on the times in which these people lived. They publish their stories on https://genealogyensemble.com, and polished their favourites for the book. The result is a volume of easy-to-read articles, filled with fascinating bits of social history, and with enough footnotes to satisfy the most exacting genealogist or historian.

Meet:

Fille du roi Anne Thomas, who married master carpenter Claude Jodoin in Montreal way back in 1666;

Felicité Poulin, 18th-century career woman, Ursuline nun and matchmaker;

Stanley Bagg, Massachusetts-born merchant who helped build the Lachine Canal in the 1820s;

Gospel singer Edward McHugh, whose 1910-period debut at the Montreal Hunt Club launched an international career;

William Anglin, respected Victorian-era Kingston, Ontario surgeon and wannabe thought-reader.

and many more.

The authors hope that Beads in a Necklace will serve as a model for people from any country or culture to write up their own family histories. They will be making presentations at Montreal-area libraries to share what they have learned about writing and publishing family history.

If you are a genealogist, a creative writer, or are the kind of person who loves reading about the lives of ordinary people whose real-life actions and relationships were discovered within piles of papers, historical photos and old newspaper clippings, Beads in a Necklace is for you.

A self-published paperback is on sale for $20 in Montreal at Livres Presque 9/Nearly New Books, 5885 Sherbrooke O; Montreal, Quebec H4A 1X6, 514 482-7323.

An Amazon Kindle edition is available for $3.89.