In this article I refer to Robert Stanley Bagg by his middle name since it was the name by which he was best known. In other articles I have referred to him as RSB to differentiate him from his father, Stanley Clark Bagg (SCB) and his grandfather, Stanley Bagg.

My great-grandfather Robert Stanley Clark Bagg, or R. Stanley Bagg (1848-1912), was born with the proverbial silver spoon in his mouth, however, working in the family real estate business was not what he really wanted to do in life. It wasn’t until after he retired that he was able to follow his true passion: politics.

I never heard any family stories about Stanley, perhaps because he died several years before my mother was born. It wasn’t until Montreal’s two major English-language newspapers were digitized a few years ago that I learned about his various interests and activities. In fact, his name appeared in Montreal newspapers frequently, especially after the late 1890s when he became active in the Conservative party.

Stanley was the second child of Montreal notary and land-owner Stanley Clark Bagg (1820-1873) and Philadelphia-born Catharine Mitcheson (1821-1914). The couple’s first child died before Stanley was born. Three younger sisters, Katharine, Amelia and Mary, were born in 1850, 1852 and 1854, and a fourth sister, Helen, arrived in 1861. Even as a child, Stanley must have been told that he would have a leadership role in the family, not only as the eldest, but also as the only male.

According to his obituary in the Montreal Gazette,1 Stanley studied law at McGill University and passed the bar in 1873. He then left Montreal for England, intending to further his studies, however, his father died unexpectedly in August of that year and Stanley came home. For a short time, he was in partnership with lawyer Donald Macmaster, sharing an office on St. James Street, in the old business heart of the city, but he gave up his legal practice to concentrate on the administration of his late father’s real estate. Nevertheless, throughout his life, Stanley identified himself as a lawyer or an advocate, a term used to refer to the practice of Quebec’s civil law.

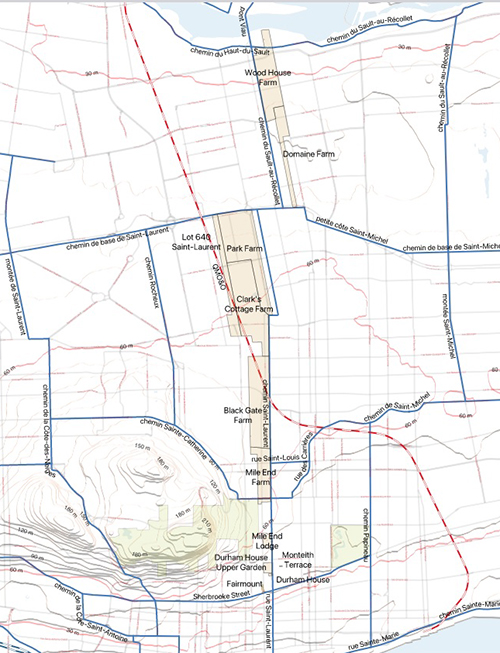

The job Stanley undertook as administrator of his father’s estate was not an easy one. Montreal was rapidly expanding, with thousands of new immigrants arriving, manufacturing, railroads and industries expanding and construction of new residences ongoing. The farmland that comprised the vast S. C. Bagg Estate, mostly located on the west side of St. Laurent Boulevard in a corridor north of Sherbrooke Street, benefited from the city’s growth. Sales, mainly of residential properties, became a profitable business.

Stanley does not seem to have been interested in developing and promoting housing or commercial real estate projects himself, but he did decide which pieces of land to subdivide into lots and he supervised sales. The estate also rented small residential and commercial buildings, and some of the land was sold to the city for civic projects such as parks.

He encountered many unexpected headaches over the years. He had to ask the provincial government to pass a special law in 1875 to override a provision in SCB’s will in order to make the lot prices competitive.2 There were misunderstandings in 1889-91 over which properties were part of the estate and which belonged to the five children. And Sister Helen’s husband disappeared under mysterious circumstances in 1897, owing the Baggs large sums of money. Although Stanley was the main administrator of his father’s estate, several family members acted as advisors. His mother had a great deal of input, and sister Amelia kept track of some of the property sales. When a major decision had to be made, family members got together to discuss it, or if that was not possible, they communicated through letters.

When Stanley announced his retirement as of January, 1901, his mother arranged to hire someone to succeed him, and she wrote Stanley a thank-you letter.3 She described her husband’s unexpected death as a calamity for the family, especially for Stanley who was “so young and inexperienced in the ways of the world.” She commended Stanley for the “able, honourable and efficient manner” in which he had performed his arduous duties for 27 years. She added, “I am most anxious that you should have a complete rest from all the worry and anxiety that is unavoidably connected with the responsible position you have occupied for such a long time – and while personally I shall greatly miss you, I hope that your absence and a complete change will allow you to regain your usual health and strength.”

One activity Stanley found helped to restore his health was travel, especially ocean voyages. Perhaps he got the travel bug when he was 20 and spent a year exploring the highlights of Europe with his parents, his aunt and his sisters. In 1875, Stanley visited England again with his mother and one of his sisters, and he returned to Europe with his new wife, Clara Smithers, on their two-month-long honeymoon in the summer of 1882.

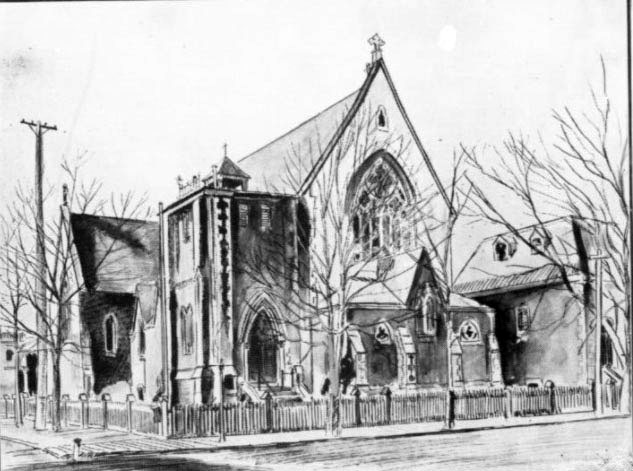

Image source: St. Martin’s Church, Historical Sketch of St. Martin’s Church : 1874-1902, Montreal, Canada, 1902?; Canadiana, https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.85997 Accessed June 14, 2023.

In 1891, he and Clara spent an extended period of time in England, taking along their two young daughters. That year’s Census of England showed Stanley, Clara, the children, a governess and a cook staying in a lodging house in St. George Hanover Square, in central London. Ten years later, after his retirement, Stanley returned to Europe, this time touring for eight months.

While real estate management, legal training and travel seem to have been family traditions, so was military service. Stanley’s father served in the military, and his grandfather was a major in the 1st Battalion Loyal Volunteers during the Rebellion of 1837. His great-grandfather Phineas Bagg had served during the American Revolution ((1775-1783) before immigrating to Canada.

In 1877, the Canada Gazette reported that R. Stanley Bagg, gentleman, began his military service as an ensign with the 5th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers, Montreal. When he retired in 1882, he retained the rank of captain from what had become the Royal Scots Fusiliers. Although his military career was relatively short, it appears to have been a success. The Montreal Star quoted the following article about Stanley that had appeared in the paper 30 years earlier:4

“There are few better-known figures in Montreal than Captain Stanley Bagg. He was an enthusiastic volunteer and belonged to the old 5th Royals before and after they had become a kilted regiment. At the time of the ship laborers’ riots in Quebec, when several regiments of Montreal were sent to restore order and liberate the regular garrison, who were practically prisoners in the Citadel, the 5th Royal Scots were marched up Mountain Hill and the honor of leading them was conferred by the colonel of the regiment on Captain Bagg owing to his height and commanding presence. Captain Bagg has always been an ardent supporter of and participant in athletic sports. A good rider and one of the old Dowell school of boxers, he kept himself in such first-class condition that he can stand almost any fatigue.”

I had read the letter written by Stanley’s mother about his retirement many years ago, and it had left me with an image of my great-grandfather as a tired and anxious man. It was a revelation to find this newspaper article and realize that he had indeed once been a strong leader and an athlete.

This article is also posted on the collaborative family history blog Genealogy Ensemble.

Footnotes:

1. “R. Stanley Bagg Died Yesterday,” The Gazette, July 23, 1912, p. 4, accessed June 9, 2024.

2. “38 Vict. cap. XCIV, assented to 23 February 1875”, Statutes of the Province of Quebec passed in the thirty-eighth year of the reign of Her Majesty Queen Victoria, part 1, p. 474, https://books.google.ca, accessed June 9, 2024

3. Catharine Mitcheson Bagg, Correspondence, P070/B6.4, Bagg Family Fonds, McCord Stewart Museum, https://collections.musee-mccord-stewart.ca/en/objects/details/176488; classification scheme; personal documents; correspondence. Accessed June 14, 2024.

4. “From the Star Files 30 Years Ago Today” The Montreal Star, Sept. 17, 1909, p. 10, www.newspapers.com, accessed June 9, 2024.

See also:

Janice Hamilton, “Bagg Family Dispute part 1: Stanley Clark Bagg’s Estate”, Writing Up the Ancestors, Dec. 13, 2023, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2023/12/bagg-family-dispute-part-1-stanley-clark-baggs-estate.html

Janice Hamilton, “The Bagg Family Dispute part 2”, Writing Up the Ancestors, Feb. 14, 2024, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2024/02/the-bagg-family-dispute-part-2.html

Janice Hamilton, “Helen Frances Bagg: A Happy Exile”, Writing Up the Ancestors, Jan. 6, 2016, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2016/01/helen-frances-bagg-happy-exile.html

Janice Hamilton, “Continental Notes for Public Circulation”, Writing Up the Ancestors, April 8, 2020, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2020/04/continental-notes-for-public-circulation.html

Janice Hamilton, “Aunt Amelia’s Ledger”, Writing Up the Ancestors, April 26, 2023, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2023/04/aunt-amelias-ledger.html

Clara Smithers Weds R. Stanley Bagg, Writing Up the Ancestors, March 2, 2014, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2014/03/clara-smithers-weds-r-stanley-bagg.html

Janice Hamilton, “The Life and Times of Stanley Bagg, 1788-1853”, Writing Up the Ancestors, Oct. 5, 2016, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2016/10/the-life-and-times-of-stanley-bagg-1788.html