Clark Street in Montreal’s Mile End neighbourhood features two-storey row houses, most of them red brick or grey stone, set back a few feet from the sidewalk. Two hundred years ago, this now densely populated street was just a gleam in the eye of my four-times great-grandfather John Clark (1767-1827), who owned that land. Today, Clark Street looks remarkably similar to the way he envisioned it.

John must have foreseen that his farmland would someday get swallowed up by the expanding city. He wanted to see it developed properly, and he wanted his descendants to profit from it. Thus, he carefully outlined his development vision in his last will and testament.

A native of County Durham in northeast England, John Clark1 immigrated to Montreal with his wife, Mary Mitcheson, and their young daughter around 1797 and he became a butcher and an inspector of beef and pork.

He probably had a nest egg of cash because he soon bought property here. In 1799, he purchased a property on Montreal’s La Gauchetière Street. Perhaps the Clark family lived there. When he sold it 11 years later, the deeds showed it to be a double lot including two houses and several other buildings..2

Between 1804 and 1814, John purchased several neighbouring farms north of the city limits of Montreal.3 He purchased these properties from French Canadian farmers, then named them Mile End Farm, Blackgate Farm and Clark Cottage Farm. The land, including several houses, barns, stables and outbuildings, was on the west side of Saint Lawrence Street, now known as Saint-Laurent Boulevard and one of the city’s major arteries. At the time, this was the main road to the countryside, leading past the eastern flank of Mount Royal to the Rivière des Prairies on the north side of Montreal Island.

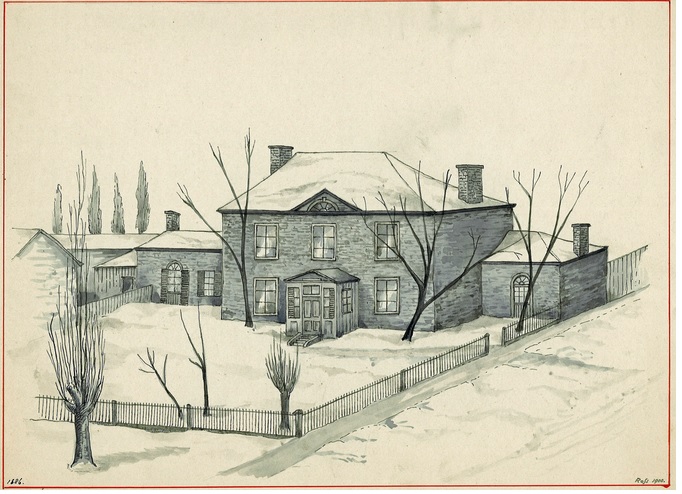

The area was rural, consisting primarily of fields of wheat, oats and peas, as well as pastureland, fruit orchards and woodlots. Both John and Mary had grown up in rural England, so they preferred to live in the countryside rather than in the crowded city. The Clarks’ grey stone house, called Mile End Lodge, was built around 1815 on Saint Lawrence Street, between what are now Bagg and Duluth streets. They had few neighbours: most Montrealers, especially recent immigrants from Britain like them, lived in town.

Land ownership was important. It conferred social status, it carried the right to vote, and land was a financial tool, commonly used as security for loans. I do not know for sure why John purchased so much land, but even in the short term, it was a smart decision: the soil was fertile and the area was close to the city, where there was a growing demand for meat and produce.

John probably wanted to graze his own cattle on that land, and to grow timothy hay for them. Meanwhile, in 1816, he placed an advertisement in the Montreal Herald saying he was willing to pasture cattle on his property for between eight and 10 shillings per cow.4

John probably collected rental income from these farms. It was not uncommon for members of the city’s elite, and for skilled tradesmen such as John, to purchase land and rent it to local farmers. He went one imaginative step further and, in 1810, leased a two-storey house on the Mile End Farm to father and son Phineas and Stanley Bagg to operate as a tavern.5 The building was located at a major intersection on St. Lawrence Street, so it was in an excellent location for thirsty travellers.

Phineas and Stanley ran the Mile End Tavern until 1818. The following year, Stanley married John’s daughter, Mary Ann. As a wedding present, John gave them a lot on St. Lawrence Street, including a two-storey house he named Durham House, that he had purchased in 1814.6

John may have had an emotional attachment to the Mile End Farm and Durham House, but he certainly saw his land as a long-term investment. The population of Montreal had increased from about 6000 in 1780 to 20,000 in 1820, and he foresaw this area would eventually be developed.

In 1825, at age 58, John wrote his will, leaving his properties to Mary Ann and to his young grandson, Stanley Clark Bagg.7

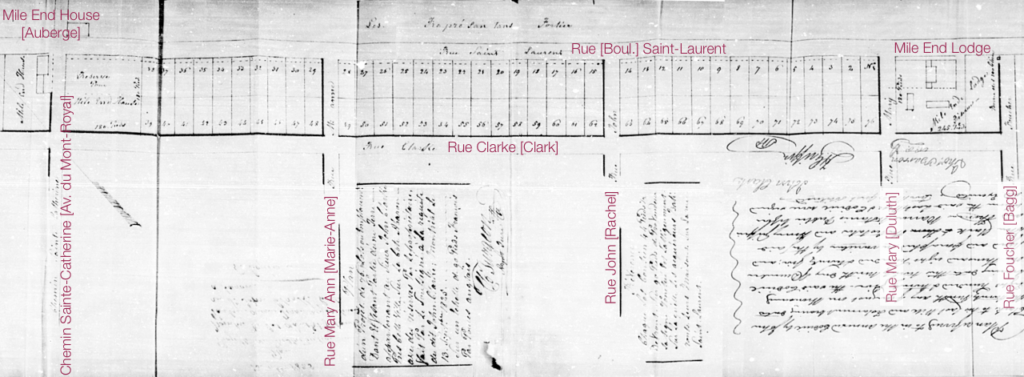

He added a codicil a few months later that included a plan for housing lots on St. Lawrence Street and on the yet to be created Clark Street, one block west. He specified that the lots should be 44 feet wide by 90 feet deep, and that the buildings should be built of stone or brick and set back from the road.8

John’s codicil also specified that the sale of the lots were subject to a rente constituée, meaning that, in addition to the initial cost of the property, the buyer was to pay the vendor an amount every year, usually about 6% of the property’s value. This was a common practice in Quebec, designed to provide funds to the seller’s family members for several generations. However, when Clark Street was finally developed decades after John’s death, buyers were not interested in this old-fashioned practice and the rente constituée was eliminated.9

Meanwhile, most of the property lines and all of the street rights-of-way shown on the plan in John’s will are still in effect today. Also, the specifications for building quality were respected, and similar conditions were imposed by neighbouring landowners.

See also:

“Mile End Tavern,” Writing Up the Ancestors, Oct. 21, 2013, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2013/10/the-mile-end-tavern.html

“A Home Well Lived In”, Writing Up the Ancestors, Jan. 21, 2014, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2014/01/a-home-well-lived-in.html

“John Clark, of Durham, England,” Writing Up the Ancestors, May 29, 2014, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2014/05/john-clark-of-durham-england.html

“A Freehold Estate in Durham,” Writing Up the Ancestors, May 3, 2019, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2019/05/a-freehold-estate-in-durham_92.html

Notes and Sources:

- John Clark is usually identified as an inspector of beef and pork. There was another John Clark, a master butcher, living in Montreal at the same time. That John Clark made a will in 1804, while my John Clark made a first will in 1810 and a final one in 1825.

- Thomas Barron, notarial act #2876, “Deed of sale John Clark to William Scott,” 18 Oct. 1810, BAnQ.

- These properties are listed in John Clark’s will, (Henry Griffin, notarial act #5989, “Last Will and Testament of Mr. John Clark of Montreal,” 29 August 1825, BAnQ) and in the inventory of his grandson’s estate (Joseph-Augustin Labadie, notarial act #16733, “Inventory of the Estate of the Late Stanley Clark Bagg Esq.” 7 June, 1875, BAnQ.)

- Jennifer L. Waywell, “Farm Leases and Agriculture on the Island of Montreal 1780-1820,” Dept. of History, Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research, McGill University, 1989, p. 88; https://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.item?id=TC-QMM-59553&op=pdf&app=Library(accessed May 14, 2019)

- J.A. Gray, notarial act, “Lease for five years John Clark to Phineas and Stanley Bagg,” 17 Oct. 1810, BAnQ.

- The marriage contract is attached to records for lot 110, Saint-Laurent Ward, Montreal, p. 395, Registre foncier du Québec online database.

- Henry Griffin, notarial act #5989, “Last Will and Testament of Mr. John Clark of Montreal,” 29 August 1825, BAnQ

- Clark Street as laid out in the plan attached to John’s codicil ran from just south of the city limits (Bagg St. near Duluth) to Saint Catherine Road (now Mont-Royal Ave). Clark Street was developed in segments throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, with the first part, around Mile End Lodge, subdivided in 1873. In the early days, a section of Clark Street was called Mitcheson Street (Mitcheson was John’s wife’s name), but by 1912, it became Clark Street along its length.

- The rente constituée was often used in France, England and French Canada. In those days, there was no modern money-lending system, so people could rent land for an annual sum. The borrower/purchaser could redeem the rent, however, the capital value of the property was not reduced by previous rent payments. John Clark and his grandson Stanley Clark Bagg complicated things by using testamentary substitutes to require that their real estate be subject to such arrangements far into the future. Their wills specified that the actual beneficiary was three generations down, while the intervening generations were responsible for keeping the estate in good shape for their children. When the Bagg and Clark properties were subdivided in the late 19th century, the Quebec legislature passed an act to end the substitution.

Image Credits:

Mile End Lodge, watercolour by John Hugh Ross, copyright Stewart Museum, 1970, 1847

Plan attached to codicil to the last will and testament of John Clark, December 1825, BAnQ, CN601 S187.

Further Reading:

Justin Bur, Yves Desjardins, Jean-Claude Robert, Bernard Vallee and Joshua Wolfe, Dictionnaire Historique du Plateau Mont-Royal, Montreal, Les Éditions Écosociété, 2017. Yves Dejardins,Histoire du Mile End, Québec: Les éditions du Septentrion, 2017.

Justin Bur, “À la recherché du cheval perdu de Stanley Bagg, et des origins du Mile End,” Joanne Burgess et al, Collecting Knowledge: New Dialogues on McCord Museum Collections, Montreal: Éditions MultiMondes, 2015.

Philippe Du Berger’s flickr collection of historic photos and maps of Montreal, this page focusing on Clark Street, https://www.flickr.com/photos/urbexplo/albums/72157627738146558

Sherry Olson and Patricia Thornton, Peopling the North American City, Montreal 1840-1900. Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press, 2011.

Alan M. Stewart, “Settling an 18th-Century Faubourg: Property and Family in the Saint-Laurent Suburb, 1735-1810,” Dept. of History, Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research, McGill University, 1988, http://digitool.Library.McGill.CA:80/R/-?func=dbin-jump-full&object_id=64109&silo_library=GEN01 (accessed May 20, 2019).

This article is also posted on https://.genealogyensemble.com