Sisters Margaret (born 1781), Elizabeth (born 1786) and Jane Mitcheson (born 1793) grew up together on their parents’ farm in County Durham, England, but when they became adults, their lives followed very different paths. The eldest married a much older man who provided her with financial security, the middle sister was swept off her feet by a tenant farmer and the youngest married a mariner who was often away at sea.

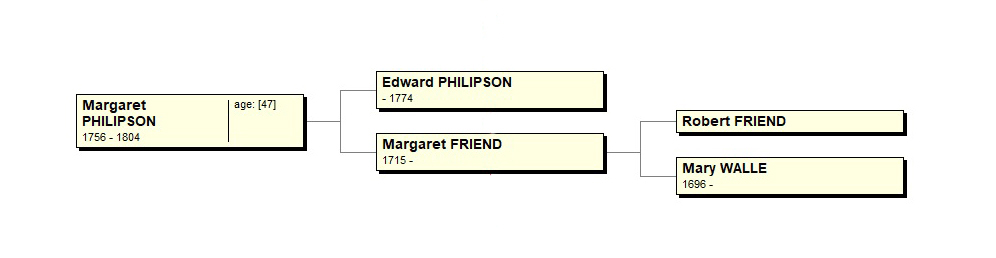

The daughters of yeoman farmer Joseph Mitcheson and his wife Margaret Philipson, they were baptized at Lanchester Parish Church and grew up in the rolling countryside of northeast England. Their mother died in 1804, when Jane would have been just nine years old.

They had two older siblings, Mary (born 1776) and Robert (born 1779) who both immigrated to North America, and another brother, William (born 1783), an anchor manufacturer who lived near the docks of London. (Mary and Robert were both my direct ancestors since Mary’s grandson, Stanley Clark Bagg, married Robert’s daughter Catharine Mitcheson in 1844, so these three sisters were my 4x and 5x great-aunts.

Their grandfather Robert Mitcheson (-1784) left each of his older grandchildren 50 pounds, part of which could be spent on their care and education and the rest given to them when they turned 21. In his will, written in 1803, their father also left them between 100 and 150 pounds each,1 although he gave the two youngest, Elizabeth and Jane, their money in 1807.

Margaret Dodd

Margaret would have been considered as having married well when she wed gentleman Thomas Dodd (1743-1823) at Whickham Parish Church in 1808.2 The Dodd lineage in northern County Durham can be traced back to 1645, and his family owned a farm called Woodhouse, located in Woodside Ryton Township.

Thomas was in his sixties and Margaret was 27 when they married. They had five children, three of whom lived to adulthood, although their only surviving son, Thomas Anthony Humble Dodd (1824-1899), was born after his father had died. Thomas grew up to be a well-known Newcastle surgeon and married his cousin, Frances Jane Mitcheson (1824-1898), daughter of the anchor maker.3

Thomas Dodd senior was an early pioneer of Methodism, founded in the 18th century by English minister John Wesley. Wesley often preached to large crowds outdoors. According to the late Durham-based genealogist Geoff Nicholson, John Wesley may have preached in the fields at Dent’s Hall, near Ryton, and Thomas may have met Wesley.4

After her husband’s death, Margaret remained at Woodhouse. In 1824, 1825 and 1827, the property was listed as owned and occupied by the executors of Thomas Dodd’s estate, but according to the 1830 land tax returns, it was “Property of Mrs. Dodd, occupied by Mrs. Dodd.”5

She was also a farmer. A local directory published in 1828 listed Margaret Dodd as a farmer in Woodside Ryton Township,6 and the 1841 U.K. census did the same.

The 1851 census found son Thomas A. H. Dodd as head of the household, living at Woodhouse with his wife and two small children, his mother and two servants. Margaret was listed as an annuitant, meaning she had her own income. The census noted that Thomas was a surgeon, and that the farm had 96 acres and employed two labourers.

When the 1861 census-taker came around, Margaret was once again head of the household, living with her widowed daughter Mary Robson and a house servant. Margaret died in October, 1864, age 83, and was buried with her husband in Holy Cross Parish Churchyard, Ryton.7

Elizabeth Maughan

While researching Margaret was straightforward, finding records of her sister Elizabeth’s life was more challenging. What I did find suggests that Elizabeth’s life was far from easy.

She was just 20 when she married farmer John Maughan, of Shotley, Northumberland, in 1806 at Whickham Parish Church.8 They lived in Shotley, a sparsely inhabited parish in southern Northumberland, located between the River Derwent and the town of Hexham. Its soil consists of sandy clay, and coal, silver, lead and iron have been produced in the area.

Elizabeth might have been lonely there, but she probably didn’t have much time to think about it as she gave birth to at least 10 children.9 Several of them died young, but Joseph (b. 1810), Margaret (b. 1814), Isabella (b. 1816), Mary (b. 1817) and possibly William (b. 1823) grew to adulthood.

The family eventually appears to have left Shotley. In 1842, my Montreal ancestors Stanley Bagg and his 21-year-old son Stanley Clark Bagg travelled to England. In an account of the trip, Stanley Clark Bagg mentioned that they visited his great-aunts Mrs. Dodd near Ryton and Mrs. Maughan in Sunderland, in northeastern County Durham.11

Some genealogists suggest Elizabeth died in Hexham, Northumberland in 1839, but in that case, the Baggs would not been able to visit her. The 1841 census counted a John Maughan, agricultural labourer, and Elizabeth Maughan, age 55, in Sunderland, along with 15-year-old Thomas Maughan, so this may have been the family.12 I do not know when Elizabeth died.

As for the youngest sister, Jane, she married master mariner David Mainland in 1812. About 10 years later, the family moved to London. Jane died in London in 1825 and their son David married his widowed cousin Mary Ann (Mitcheson) Eady in 1849. Jane’s family will be the subject of my next post.

Notes:

According to genealogist Geoff Nicholson, Margaret and Thomas Dodd’s children were: Margaret (c.1810-1851) m. John Milburn; Isabella Ann (1815-1822), Mary (1817- ) m. Rob. Robson or Ritson; Anthony Humble (1818-1821) and Thomas Anthony Humble (1824-1899) m. Frances Jane Mitcheson.

Elizabeth and John Maughan’s daughter Mary (born 181712)) moved to Montreal, Canada, where her Aunt Mary (MItcheson) Clark lived. Mary Maughan married merchant William Footner in Montreal in September, 1840,13 and she gave birth to one of her three children at Mile End Lodge, a large farmhouse that belonged to her aunt. The Footner family later moved to the United States and Mary died in Minnesota in 1901. (There was another William Footner, an architect, married to another Mary, in Montreal in the mid to late 1800s.)

See also:

This article has simultaneously been posted on https://genealogyensemble.com

The Lucy H. Anglin Family Tree on Ancestry Public Member Trees. Numerous members of the Mitcheson family in Durham, including several generations of men named Robert Mitcheson, as well as their descendants in Philadelphia and Montreal, have now been listed on this tree.

Janice Hamilton, “Mary Mitcheson Clark”, Writing Up the Ancestors, May 16, 2014, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2014/05/mary-mitcheson-clark.html

Janice Hamilton, “Philadelphia and the Mitcheson Family,” Writing Up the Ancestors, Nov. 22, 2013, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2013/11/philadelphia-and-mitcheson-family.html

Janice Hamilton, “Fanny in Philly” Writing Up the Ancestors, March 30, 2014, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2014/03/fanny-in-philly.html

Janice Hamilton, “Robert Mitcheson’s Last Will and Testament”, Writing Up the Ancestors, March 1, 2022, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2022/03/robert-mitchesons-last-will-and-testament.html

Sources:

1. Will of Joseph Mitcheson, yeoman, Iveston, Durham, The National Archives, Wills 1384-1858 (http://nationalarchives.gov.uk, search for Joseph Mitcheson, accessed Nov. 18, 2010), The National Archives, Kew – Prerogative Court of Canterbury, 9 February, 1822.

2. England, Select Marriages, 1538-1973, Ancestry.com. (www.ancestry.ca, database on-line, entry for Margaret Mitcheson, accessed April 19, 2022), citing England, Marriages, 1538–1973. Salt Lake City, Utah: FamilySearch, 2013.

3 London and Surrey, England, Marriage Bonds and Allegations, 1597-1921, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.ca, database on-line, entry for Thomas Anthony Humble Dodd, 1848, accessed April 19, 2022), citing Marriage Bonds and Allegations. London, England: London Metropolitan Archives.

4 E-mail correspondence from Geoff Nicholson about the Dodd family, June 13, 2009.

5 Durham County Record Office. Quarter Sessions – Land Tax Returns, Chester Ward West 1759-1830, www.durhamrecordsoffice.org.uk, search for Dodd, viewed April 19, 2022.

6 The History, Directory and Gazetteer of Durham and Northumberland, Vol 2, by Wm. Parson and Wm. White, W. White and Company, 1828, p. 186, Google Books, search for Margaret Dodd, accessed April 19, 2022.

7 Find a Grave (www.findagrave.com, database online, search for Margaret Dodd, accessed April 19, 2022), https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/231216340/margaret-dodd.

8. England, Select Marriages, 1538-1973 Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.ca, database on-line, entry for Elizabeth Mitcheson, Whickham, accessed April 10, 2022), citing England, Marriages, 1538–1973. Salt Lake City, Utah: FamilySearch, 2013.

9. England Births and Christenings, 1538-1975, Familysearch.org, database online, entry for John Maughan and spouse Elizabeth, Shotley; accessed April 10, 2022.

10. Letter from Stanley Clark Bagg to Rev. R. M. Mitcheson, Dec. 6, 1842, probably transcribed by Stanley Bagg Lindsay; Lindsay family collection.

11.1841 England Census, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.ca, database on-line, entry for Elizabeth Maughan, Bishop Wearmouth, accessed April 10, 2022), citing Class: HO107; Piece: 310; Book: 4; Civil Parish: Bishop Wearmouth; County: Durham; Enumeration District: 4; Folio: 13; Page: 21; Line: 1; GSU roll: 241353, original dataCensus Returns of England and Wales, 1841. Kew, Surrey, England: The National Archives of the UK (TNA): Public Record Office (PRO), 1841.

12 “England Births and Christenings, 1538-1975”, database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:JWVX-TMS : 20 March 2020), entry for Mary Maughan, accessed April 19, 2022).

13. Quebec, Canada, Vital and Church Records (Drouin Collection), 1621-1968, Ancestry.com, (www.ancestry.ca, database on-line, entry for Mary Maughan, accessed April 19, 2022), citing Institut Généalogique Drouin; Montreal, Quebec, Canada; Drouin Collection; Author: Gabriel Drouin, comp.