When my grandfather was a teenager in rural Saskatchewan, he hunted bobcats for cash. He would take his rifle, ride his pony across the prairie and, whenever he saw a bobcat, he would chase it. When frightened, bobcats often climb trees, but a tree doesn’t afford any safety from a boy and his rifle. After killing the animal, my grandfather would skin it. In the late 1880s, the fur of a bobcat brought him 25 cents.1

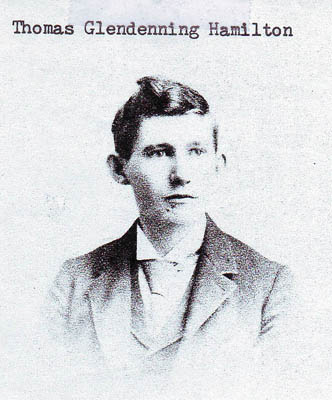

This was one of the stories Thomas Glendenning (T.G.) Hamilton,2 used to tell his own children about his adventures growing up in newly founded Saskatoon, Saskatchewan.

T.G. was born in 1873 in Scarborough, Ontario, the fifth of the six children of farmer James Hamilton and his wife Isabella Glendenning. His father was a member of a Toronto-based group called the Temperance Colonization Society that was passionately opposed to the use of alcohol. The group’s members decided to establish a dry community in western Canada, which had recently been opened to settlement. In 1882, James and his eldest son, Robbie, went west as part of an advance party of the Temperance Colonization Society. They were credited with picking the settlement’s location on the banks of the South Saskatchewan River.3

James and Robbie quickly built a sod hut and started construction of a proper house for the family, but neither structure could protect them from the bitter cold, so they spent much of that first winter in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan. Wife Isabella, their daughter Maggie and their other sons came west in 1883, travelling by train as far as possible and completing the journey by ox cart. T.G. was almost 10 years old when he arrived in Saskatoon.

The Hamiltons experienced many disappointments in Saskatoon. The temperance colony was unable to achieve its goal of banning alcohol in the community. James died of a heart attack in 1885 and Maggie died of typhoid the following year.4 Moreover, the winters were frigid and summer drought killed the crops.

Their lives were also disrupted by the Northwest Rebellion of 1885. The Métis people and their First Nations allies were upset because they were losing their hunting and fishing territories to the new settlers. Métis militants established a provisional government, led by Louis Riel, at Batoche, north of Saskatoon.5 The government in Ottawa sent militia forces to deal with the situation.

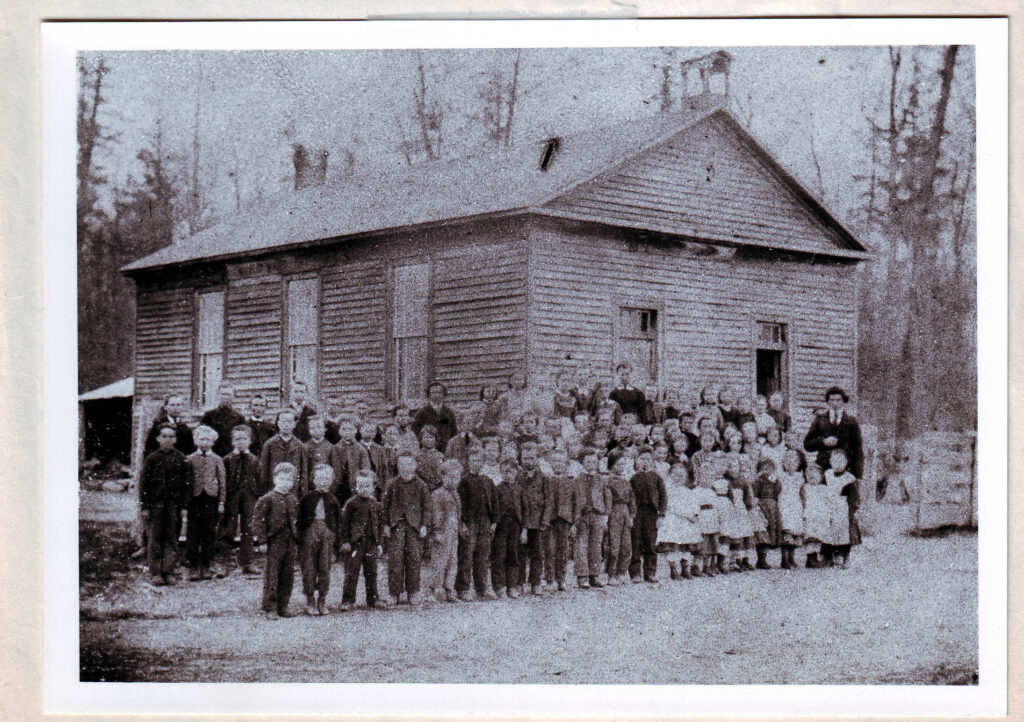

T.G. was at school one day when Dakota Chief Whitecap passed through Saskatoon on his way to Batoche to meet with Riel. When Whitecap entered the one-room schoolhouse, no one knew why he was there, or whether he was a friend or a foe. No one said a word as the First Nations leader walked around the classroom, touching each student on the top of the head. Then Whitecap left.6

As it turned out, Whitecap remained loyal to the Crown,7 but the memory of this event stayed with T.G. for the rest of his life.

By 1891, the widowed Isabella and her now grown sons had decided to give up on pioneering and move to Winnipeg, Manitoba, where the young men could further their education. Isabella and three of her sons left T.G., now 18, and his brother Jim, 21, to wind up the farm and make their own way the 780 kilometers from Saskatoon to Winnipeg. The brief account of their journey became a cherished family legend.

The story goes that they ran out of money before they reached Winnipeg, so they sold their ponies and buckboard to a farmer for a promissory note for $30. They never got the money and they had to walk the last miles, foot-sore, dusty and weary. They finally reached their destination some three weeks after leaving Saskatoon. Later, T. G. laughed at the memory of the funny sight they must have made, trudging through the streets of Winnipeg for the first time.8

Photos courtesy Fran Solar

Notes and Sources

- That would be about $6 today. Bobcat trapping is still legal for licensed trappers in Saskatchewan. I heard this story in an interview with my uncle (see footnote 6.)

- As an adult, Dr. Thomas Glendenning Hamilton was known as T.G. or T. Glen Hamilton. When he was a child, people called him Thomas. Since I have referred to him as T.G. in several other articles, for the sake of clarity, he is T.G. here also.

- Historical Association of Saskatoon. Narratives of Saskatoon, 1882-1912 by men of the city: Prepared by a committee of the Historical Association of Saskatoon. [Saskatoon]: University Book-Store, [1927], p. 9, Peel’s Prairie Provinces, Peel 3742, http://peel.library.ualberta.ca/bibliography/3742/11.htmlaccessed Jan. 28, 2019

- James died on a trip back east and is buried next to his parents in St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Cemetery, Scarborough. Maggie was buried in Saskatoon, but her remains were eventually moved to the Hamilton family plot in Elmwood Cemetery, Winnipeg and her headstone is there.

- Bob Beal, Rod Macleod, “North-West Rebellion”, The Canadian Encyclopedia, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/north-west-rebellion, accessed Jan. 28, 2019

- Dr. Glen Forrester Hamilton, in a videotaped interview done by James B. Nickels, Department of Psychology, University of Manitoba; Winnipeg, Manitoba, July, 1987; DVD copy in the author’s possession.

- Following the Battle of Batoche, Chief Whitecap was arrested for treason, but was found not guilty. Today, he is recognized as one of the founders of Saskatoon and a public school is named after him. https://www.spsd.sk.ca/school/chiefwhitecap/About/Pages/default.aspxaccessed Jan. 28, 2019

- Margaret Hamilton Bach, “The Story of the Canadian Hamiltons, with genealogical information from Scotland” unpublished manuscript, Winnipeg, 1983. In 2009, I transcribed and revised my aunt’s article, adding corrections and some new information.