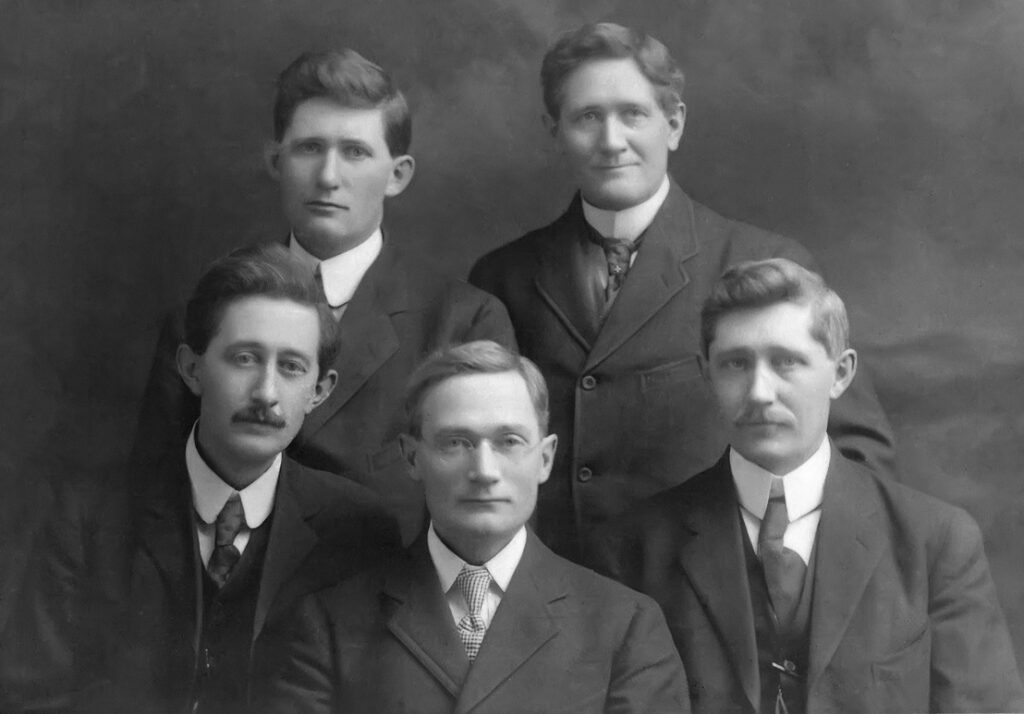

The five young men posing for a studio photograph in turn-of-the century Winnipeg look serious. They probably wouldn’t have been the life of any party, but if you needed help, no doubt each would have stepped up. They were, after all, of Scottish descent, professional men imbued with a strong Presbyterian ethic of hard work and responsibility.

They shared similar square faces, gentle eyes and wavy hair, and if you guess that they were brothers, you are right. They were my grandfather Thomas Glendenning Hamilton (known to his friends as T. G.) and his brothers Rob, Jim, John and Will.

What you couldn’t know is that there is someone missing from this photo: their only sister, Maggie, who died in 1886.

They grew up in Scarborough, Ontario on the land their immigrant grandfather had cleared. Their parents were farmer James Hamilton senior and his wife, Isabella Glendenning. Robert, born 1860, was the oldest, followed by Margaret, John Stobo, James Archibald and Thomas Glendenning. The youngest, William Oliver, was born in 1875.

James Hamilton Sr. was strongly opposed to alcohol consumption and, with western Canada opening to settlement, the family decided to help establish a temperance colony on the Prairies. In 1882, Rob accompanied his father in an advance party, leaving Isabella in Toronto with Maggie and the younger boys. The following year, the brothers and their mother joined James and Rob in the newly founded Saskatoon, Saskatchewan.

The pioneer settlement faced harsh winters, drought and food shortages, and the attempt to establish an alcohol-free community was a failure. Meanwhile, in 1885, the Northwest Rebellion took place almost on the Hamiltons’ doorstep. The rebels were the Métis people, angry that they were losing their hunting lands to the new settlers. James and Rob served as guides to the government militia forces sent to quash the rebellion, while Isabella and Maggie helped look after the wounded soldiers following the Battle of Batoche.

James Sr. had an opportunity to go back east with the troops, so he decided to visit his relatives in Ontario. While there, he suffered a massive heart attack and he was buried in Scarborough. The following year brought another blow to the family when Maggie died of typhoid at age 24.

Finally, Isabella and her sons decided to move to Winnipeg. The boys wanted to continue their studies and it had become clear that farming was not for them.

The family members separated for several transitional years. Rob went to Toronto to study for a career as an electrical inspector, while John taught school in British Columbia. Meanwhile, Isabella took Will, who was then about 15 years old, to look for a house in Winnipeg, leaving T.G. and Jim in Saskatoon. In 1891, with their father’s estate finally settled, the two brothers, ages 18 and 21, travelled by pony and buckboard the 800 dusty kilometers from Saskatoon to Winnipeg.

Back in Winnipeg, Rob helped to support the family while his brothers studied. During their student years, they all helped to pay their own expenses by teaching school.

John was the first to graduate from university, obtaining a degree in philosophy in 1892, followed by a degree in theology in 1895. Jim became a doctor, and T. G. followed his older brother into medicine, graduating in 1903. That same year, John gave up his post as a minister when he finished his medical degree in the United States. Will taught for five years, then articled in law and opened a law firm, Beveridge and Hamilton, in 1911.

Four of the brothers remained in Winnipeg for the rest of their lives, although they didn’t see each other often. Jim, who was single, and T. G. were probably the closest of the brothers, sharing a medical office downtown. Rob and his family lived in another part of the city. A quiet person and in poor health, he did not socialize much with his brothers, and neither did Will.

John and his wife and daughter lived in North Dakota, about 80 miles from Winnipeg, and they made frequent short visits to the city.

In the 1920s, T. G. and his wife Lillian became interested in psychic phenomena. At the time, this was not unusual: many people wanted to communicate with loved ones who had died in the Great War or the flu epidemic. The couple had lost their three-year-old son to the flu in 1919. They hosted séances at their home almost weekly for more than a decade, and T. G. documented the paranormal events they observed. Jim attended these meetings regularly, but the other Hamilton brothers did not.

Finally, the brothers’ deaths reunited them. They all suffered from heart problems. Rob died in 1923 and Will died suddenly at his office in 1924, at age 49. John died of a heart attack in 1932, Jim in 1934, and T. G. followed in 1935. They are all buried beside their mother, their sister and other family members in Elmwood Cemetery, Winnipeg.

Sources and Further Reading

This article relies on family histories and letters written by my late aunt, Margaret Hamilton Bach, and by Alison Mossler Wright (John’s granddaughter) and the late Olive Hamilton (Rob’s daughter).

James B. Nickels, Manitoba History, “Psychic Research in a Winnipeg Family, Reminiscences of Dr. Glen F. Hamilton,” June, 2007, http://www.mhs.mb.ca/docs/mb_history/55/psychicresearch.shtml (accessed Nov. 23, 2018)

University of Manitoba, Libraries, Hamilton Family Fonds, http://umanitoba.ca/libraries/units/archives/digital/hamilton/index.html (accessed Nov. 23, 2018)

“Louis Riel, October 22 1844- November 16, 1885”, Library and Archives Canada, http://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/politics-government/canadian-confederation/Pages/louis-riel.aspx (accessed Nov 22, 2018)