In 1841, many English-speaking citizens of Quebec could not read the civil laws that governed their everyday activities. Although Quebec had been a British colony for almost 80 years, the collection of civil laws called the Coutume de Paris (Custom of Paris) had not been translated from French into English.1

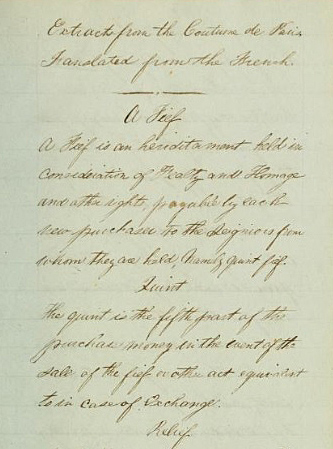

So that year, Stanley Clark Bagg (1820-1873) made his own translation of excerpts of the Coutume de Paris, completing the project shortly before he finished his four-and-a-half-year apprenticeship as a notary. Perhaps it was an assignment given to him by the notary who was supervising him, or perhaps he did the translation to help himself understand these laws.

Today this manuscript — the earliest recorded translation of the Coutume de Paris into English — is housed in the library of York University’s Osgood Hall Law School in Toronto, and it can be found online at https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/library_digital/1/

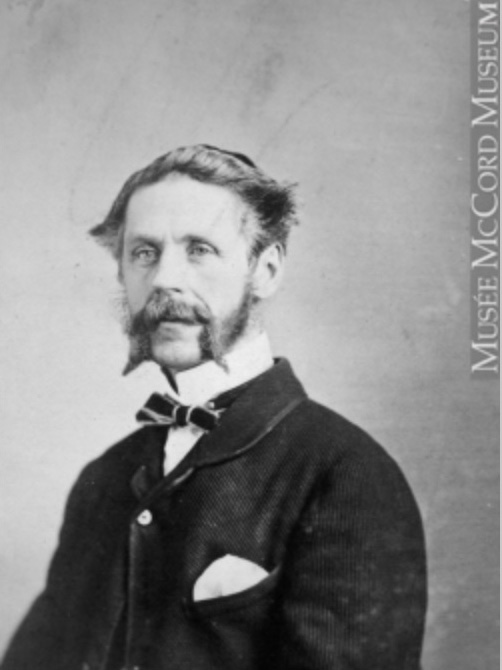

Stanley Clark Bagg, or SCB, who was my great-great-grandfather, had inherited a large amount of land on the Island of Montreal. When he turned 21 in December, 1841, he expected to take over the management of that inheritance. Perhaps he studied to become a notary to prepare for that day. He would apply his understanding of the Custom of Paris whenever he rented or sold a property. SCB served a four-year apprenticeship with notary W.S. Hunter and, in August 1841, his father indentured him for a final eight months to N.B. Doucet, a well-known Montreal notary.2

Notaries played an important role in Quebec. Besides property deeds, they drew up a variety of agreements including marriage contracts and protests when debts were not paid. In this way, they often served as mediators. They also prepared wills and made inventories of estates following death.

SCB’s translation consists of about 200 pages, neatly handwritten in a small, hardcover notebook.3 He did not include the entire body of civil laws, but focused on definitions of French legal terms in English, and English translations of laws governing rights of property ownership, marriage and inheritance. On the final page he noted, “The laws of every nation are more or less mixed with the laws of nations that have passed away, but none more than the laws of Canada, which have for their basis the jurisprudence of France and England.”

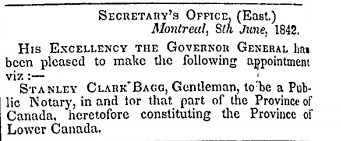

As for SCB’s own career as a notary, it was brief. His appointment was effective in June, 1842,4 but he travelled to England that summer. The first notarial act recorded in his index was a rental agreement, dated Nov. 1, 1842.

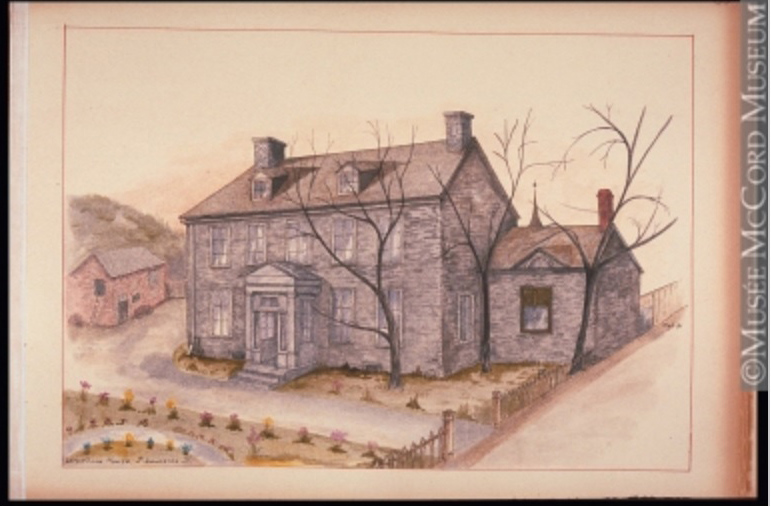

There were many notaries in Montreal and it took a while for him to become known. In 1843 and 1844, he was quite busy with a variety of clients, writing wills and leases and protesting unpaid debts. For example, he prepared a lease for his grandmother, dated 17 Jan. 1844. His index described a “lease of a two-story stone house on the continuation of St. Lawrence Street, by Mrs. Mary Clark to P.R. Turner.”5

But SCB was busy managing his own properties by the mid-1840s, and perhaps he did not find being a notary very interesting. His index shows he took several long breaks in 1846 and 1847 and only prepared two or three acts a year in the 1850s. He closed the practice completely in 1856.

Three years later, he was named a Justice of the Peace in Montreal. Numerous Justices of the Peace had been named, so they shared the workload. It must have been SCB’s turn in 1865 because records show he heard almost 40 cases that year.6

Photo Credits: Photo of Stanley Clark Bagg, 1863, by William Notman, copyright McCord Museum

Notes and Sources:

- King Louis XIV made the Coutume de Paris the civil law of New France in 1664. It did not include criminal law or cover commercial law. Some of its provisions dated from feudal times and were based on concepts such as moveable property (objects that can be moved) and immovable property (such as land and buildings), as well as community of property between married couples, provisions to protect widows and inheritances for daughters.

After the British Conquest of New France, the Royal Proclamation of 1763 introduced British Common Law to the colony, however, French Canadians resisted this new way of doing things. In 1774, the government passed the Quebec Act, bringing back the property and family laws of the Coutume de Paris, while British Common Law applied to criminal matters.

Some reforms were made in 1840, but legislators realized that the laws had to be updated to meet the needs of a changing society. The old seigneurial system of land ownership was being phased out, and new laws were needed to make it easier for commerce, investment and industrialization to expand. The new Civil Code of Lower Canada, which came into force in 1866, clearly had some roots in the Custom of Paris, making Quebec’s legal traditions unique in Canada. And to this day, Quebecers still rely on notaries to prepare their wills, property deeds and marriage contracts. - Joseph-Hilarion Jobin, “Indenture of Stanley C. Bagg to N.B. Doucet,” notarial act #2977 23 Aug 1841, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

- Bagg, Stanley Clark, “A Collection of Extracts from the Coutume de Paris: Translated from the French,” 1841. https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/library_digital/1/

- Library and Archives Canada;, Appointment, Montreal, 8 June 1842, The Canada Gazette, no. 37, Published by Authority, Kingston, June 11, 1842, p. 326; entry for Stanley Clark Bagg; http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/databases/canada-gazette/093/001060-119.01-e.php?image_id_nbr=945&document_id_nbr=1699&f=p&PHPSESSID=j1au0sblq8sejaol266jar2vp4(accessed Jan. 7, 2020).

- Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec, “Archives des notaires du Québec, Montréal District judiciaire de Montréal; Stanley Clark Bagg, 1842-1856, CN601,S11” http://bibnum2.banq.qc.ca/bna/notaires/affichage.html?serie=06M_CN601S11 (accessed Dec. 31, 2019)

- Library and Archives Canada; “Cases Before Justices of the Peace,” The Canada Gazette, vol. XXIV, no. 8, Published by Authority, Quebec: Feb. 25, 1865, p. 781, entry for Stanley Clark Bagg; http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/databases/canada-gazette/093/001060-119.01-e.php?image_id_nbr=55914&document_id_nbr=3045&f=p&PHPSESSID=oo3dok1snqetmppvat92ncmo44 (accessed Jan. 11, 2020).

To Learn More:

Wikipedia, “Custom of Paris in New France,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Custom_of_Paris_in_New_France

Wikipedia, “Civil Code of Lower Canada,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Civil_Code_of_Lower_Canada

Marianopolis College: “The Civil Code of Quebec” in Quebec History: The Quebec History Encyclopedia, http://faculty.marianopolis.edu/c.belanger/quebechistory/encyclopedia/CivilCode-QuebecHistory.htm

Bettina Bradbury. Wife to Widow. Lives, Laws and Politics in Nineteenth-Century Montreal. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2011.

Brian Young, “The Legal Landscape,” The Politics of Codification: The Lower Canadian Civil Code of 1866, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1994, https://books.google.ca/books?id=aStDI2F2SxUC&pg=PP1&dq=The+politics+of+codification&lr=&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

Notarial Acts – Key to Family History Research in Quebec

Most people in Quebec hired a notary at some time to prepare a lease, a will, a power of attorney, a deed, or some other document. The indexes to many notaries’ records, from the first days of New France up to 1937, can be found online on the website of the Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec. See http://bibnum2.banq.qc.ca/bna/notaires/ Familysearch.org and Ancestry.ca have digitized the acts of some notaries. Genealogist Jacques Gagné has posted numerous research guides to the notaries who served various communities in Quebec on the blog https://genealogyensemble.com