Hundreds of special events are taking place in 2017 to mark the City of Montreal’s 375thbirthday, but the one that means the most to me is the publication last month of a history of the Mile End district of Montreal. Some 200 years ago, that was where my three- and four-times great-grandparents lived.

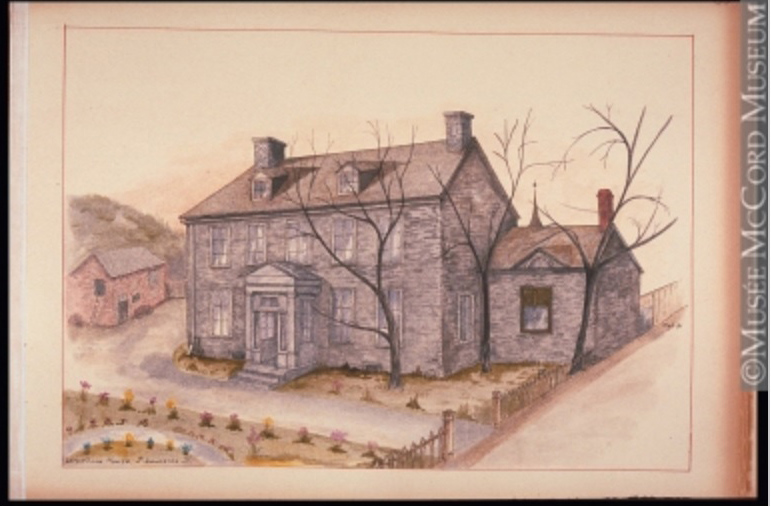

There, at the intersection of the only two roads for miles around, Stanley Bagg and his father Phineas ran an establishment called the Mile End Tavern. Their landlord and future in-law, an English-born butcher named John Clark, probably came up with the name Mile End. The tavern was at the corner of what is now Saint-Laurent Boulevard and Mont-Royal Avenue, and the whole area eventually acquired the same name.

Mile End has no formal boundaries, but it is essentially just to the northeast of Mount Royal, as far as the railroad tracks. Some of the area’s streets are known far beyond Montreal: Saint-Urbain, for example, was made famous by author Mordecai Richler, and both Saint-Viateur and Fairmount streets have bagels named after them. Other well-known streets include Laurier, Parc, Saint-Joseph and Jeanne-Mance.

It is a vibrant neighbourhood, home to musicians, teachers and software developers, trendy restaurants, second-hand shops and rows of triplex and duplex dwellings, often featuring Montreal’s iconic outdoor staircases.

Histoire du Mile End, the first book to focus on the area’s history, was written by former journalist Yves Desjardins. His journalism background shows: he has researched his subject thoroughly in newspaper accounts, archival sources and academic articles, and pulled it all together in clear, concise language. I can attest to how readable it is because, although the book is in French, I have had no trouble reading it. It helps that the book is generously illustrated with historic photos and maps.

Over the decades, Mile End has been home to waves of immigrants, starting with French Canadian job-seekers who moved to the city from the Laurentians, and including Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, Italians, Portuguese and Greeks. Many of the area’s residents worked in the nearby Peck Building, labouring in low-paying jobs in the garment industry; today, the Peck Building is home to Ubisoft, a major player in the video game industry.

Just as it takes a village to raise a child, sometimes it takes a community to write a book. Yves had help from friends and neighbours — many of them members of the local history group Mile End Memories — who gave him access to their own research and expertise. I provided him with information about my ancestors the Baggs and the Clarks, and the collaboration paid off for both of us: I was able to fill in family information he didn’t have, and he helped me understand the historical context of my ancestors’ lives.

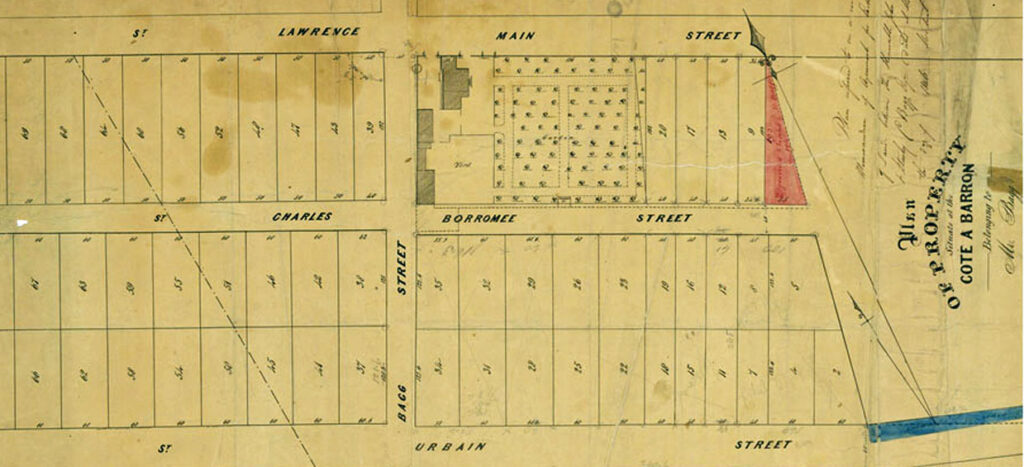

I learned that Saint-Laurent Boulevard, the traditional dividing line between the western part of the city, where the majority of English-speaking Montrealers live, and the eastern part, which is overwhelmingly French-speaking, was the only road leading north out of the city in the early 1800s. The Baggs owned much of the land on the western side of Saint-Laurent, and it remained primarily rural until the 1890s. Much of the land on the east side was owned by the Beaubien family, and early residents worked in local tanneries and quarries.

At the end of the 19th century, a group of real estate promoters from Toronto tried to develop a “strictly high class suburb” in Mile End called the Montreal Annex. While they did manage to attract a few professionals and their families, the scheme eventually failed. For decades, most of Mile End’s residents were strictly working class, or worked at skilled trades such as shoe-making and carriage-making.

Meanwhile the area experienced many growing pains as politicians argued over taxes and infrastructure, and promoters battled to provide the public transportation (by electric tram and rail) that was key to the area’s growth.

Today, as the city of Montreal rebuilds its infrastructure and controversy surrounds plans for future residential projects and transportation corridors, it seems that some things haven’t changed much.

Yves Desjardins. Histoire du Mile End, Québec: Éditions du Septentrion, 2017.

See also:

Janice Hamilton, “The Mile End Tavern”, Writing Up the Ancestors, Oct. 21, 2013, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2013/10/the-mile-end-tavern.html

Mile End Memories, http://memoire.mile-end.qc.ca/en/ This site includes articles in English and in French, photos, an interactive map that indicates the location of many historic buildings, including the Auberge du Mile End (Mile End Tavern), and a link to summer walking tours of the area.

This article is simultaneously posted on https://genealogyensemble.com