It has been 150 years since William Lyon Mackenzie King (1874-1950), Canada’s longest serving prime minister, was born in what is now Kitchener, Ontario. The anniversary of his birth passed with little fanfare, possibly because of King’s reputation as “weird Willie.” A new book called The Spiritualist Prime Minister: Volume I, William Lyon Mackenzie King and the New Revelation, by Anton Wagner, reveals what was weird about him.

Born Dec. 17, 1874, King was the grandson of William Lyon Mackenzie (1795-1861), leader of the failed Rebellion of 1837 in Upper Canada. King’s mother, Isabel, was his daughter. King grew up in Ontario with his parents and three siblings in what has been described as a happy family. He obtained several degrees from the University of Toronto and graduate degrees from Harvard University. In 1900, he was appointed Deputy Minister of Labour in Wilfred Laurier’s federal Liberal government. He was elected as a member of Parliament for the first time in 1908 and was appointed to cabinet a year later, but lost his seat in 1911 when the Liberals were defeated. He became leader of the Liberal Party in 1919, following Laurier’s death.

Over the next 21 years, he was prime minister for three stretches: 1921 to 1926, 1926 to 1930, and 1935 to 1948. During this time Canada went from having a primarily agricultural economy to becoming industrialized. King was prime minister during the difficult years of the Depression in the 1930s, and during the World War II.

Although he is said to have been a poor public speaker, King succeeded in keeping the country united through these tumultuous times. Today, many historians acknowledge him as Canada’s greatest prime minister. But King had interests and beliefs that the public did not know about. It is these activities, not his political accomplishments, that are the focus of Wagner’s book.

Raised a Presbyterian, King was a deeply religious man, but in addition to his Christian beliefs, he became a spiritualist: he was convinced of the continuity of life after death, and in the existence of a spiritual world that interacted with and guided him in the material world. Such beliefs were not uncommon at that time. Many people had lost loved ones in World War I and in the great flu epidemic of 1918, and sought to communicate with them on the other side. While it may have been acceptable for ordinary people to try to contact deceased loved ones, it was another thing for the prime minister to do so. Meanwhile, Wagner writes, King was convinced he was “an agent of God, working out His will ‘on Earth as it is in Heaven.’”

Some people have suggested that King was on the brink of insanity. Wagner speculates he may have been suffering from prolonged grief disorder. King was unmarried and had few close friends. Both his parents and two of his siblings had died by 1922, and he was undoubtedly lonely. He was particularly attached to his mother, believing that she was “pure and holy and Christ-like” and was watching over him. A large portrait of her hung in his Ottawa study, and she regularly appeared to him in dream visions.

Around 1917, King began consulting a fortune teller, having his horoscope read and consulting phrenologists, numerologists and palm readers. He participated in a séance for the first time in 1932 with the medium Etta Wriedt, and from then on took part in dozens of seances in the United States, England and Canada. At home, he began to act as a medium himself and, along with his “spiritual companion”, the married Joan Patteson, had regular table rapping conversations with spiritual entities over “the little table.”

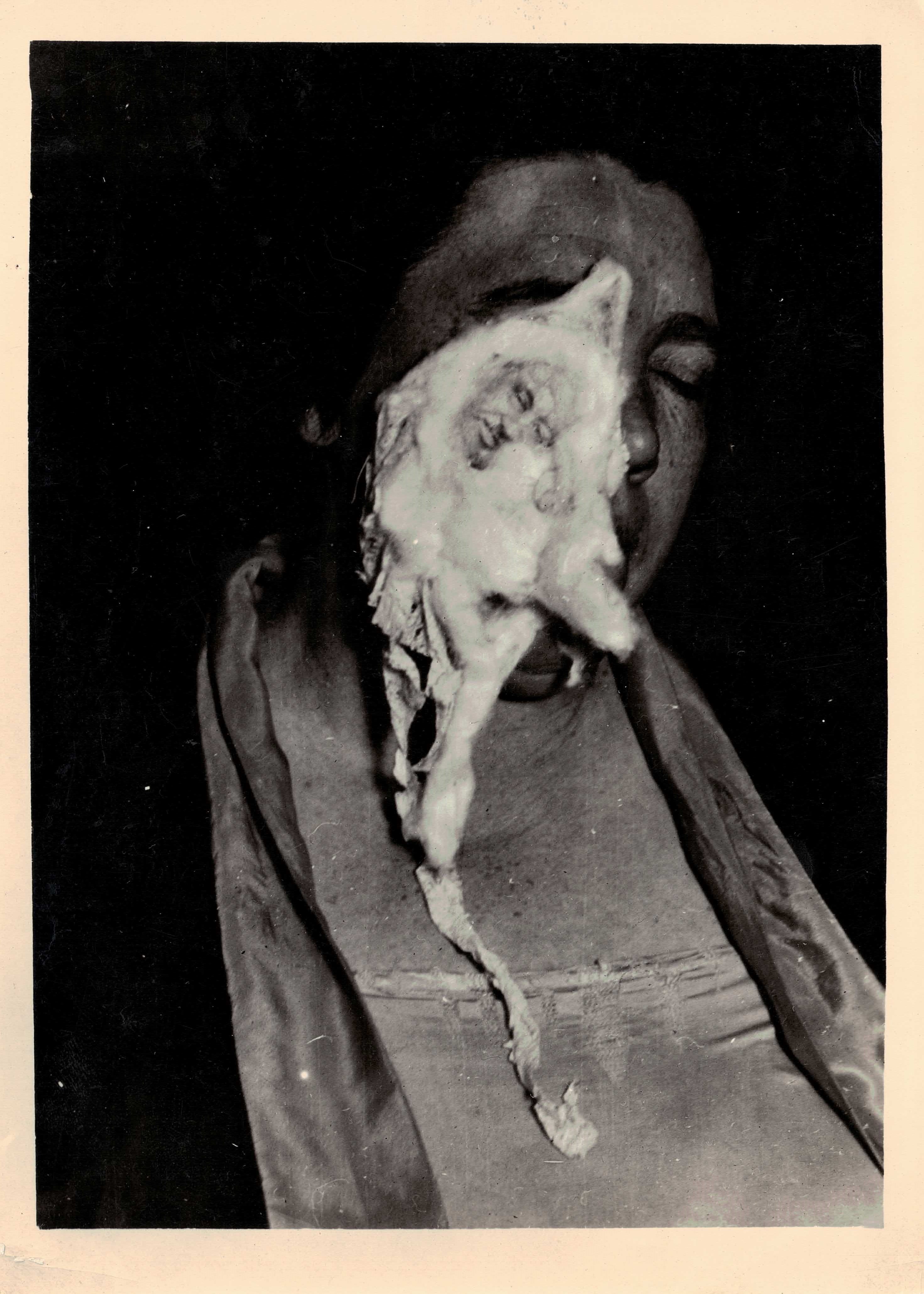

King also met and corresponded with my grandparents, psychical researchers Dr. T.G. Hamilton and his wife, Lillian, of Winnipeg. It was because of this connection that I was asked to review Wagner’s book.

A few people knew about these activities, but they were not public knowledge. King kept a diary in which he recorded his daily activities, including his occult beliefs and practices. He intended these diaries to become the basis of his memoirs, but he died before he got a chance to write them. After he died, the instructions he left concerning the diaries were unclear. Some of his executors wanted to burn them in order to preserve King’s reputation but, in the end, they were not destroyed. In fact, they were eventually transcribed, with some omissions, and the 30,000-page typed copy is available online from Library and Archives Canada.

One of the first historians to write about King’s inner life was C.P. Stacey. In A Very Double Life: the Private world of Mackenzie King, published in 1976, Stacey wrote that King often frequented prostitutes. This information, as well as revelations about King’s spiritualist beliefs, led to his reputation as being weird. But until Wagner’s book was published in 2024, those occult activities had not been studied in depth. Volume I is an exploration of King’s life as a spiritualist, while Volume II takes a closer look at the many mediums he interacted with. I have not read volume II.

Wagner is not an expert on Canadian political history. He has doctorates in drama and theatre, and has produced documentary films on arts and culture. He did, however, do extensive research for this book, not only from the primary sources of King’s diaries and letters; volume I includes a 15-page bibliography.

Volume I includes several examples of how King’s occult beliefs impacted his political decisions. Early in his political career, King consulted a fortune teller before choosing an auspicious date for an election – and he was disappointed when the prediction proved wrong. In 1937, King’s belief that he was part of a divine plan to save the world from war took him to Germany, where he badly misjudged Hitler and his intentions. And at the end of the war, King asked for advice from the recently deceased Franklin Delano Roosevelt regarding a spy scandal and what he should reveal to the Soviet Union about the development of the atom bomb.

Unfortunately, interesting as the topic is, I found the text hard to follow. So many people and events were included that the contents might have benefitted from better organization and an index, although a chronology at the end of the book does help.

The Spiritualist Prime Minister, by Anton Wagner, PhD, is published by White Crow Books in association with the Survival Research Institute of Canada.

This article is also posted on the collaborative blog https://genealogyensemble.com