Written by Janice Hamilton, with research by Justin Bur

Note: there were three generations named Stanley Bagg, so for the sake of brevity I use their initials: SCB for generation two, Stanley Clark Bagg, and RSB for generation three, Robert Stanley Bagg.

Be careful what you wish for, especially when it comes to writing a will and placing conditions on how your descendants are to use their inheritance. That was a lesson my ancestors learned the hard way.

It took a special piece of provincial legislation in 1875 and what appears to have been a family crisis before these issues were finally resolved many years later.

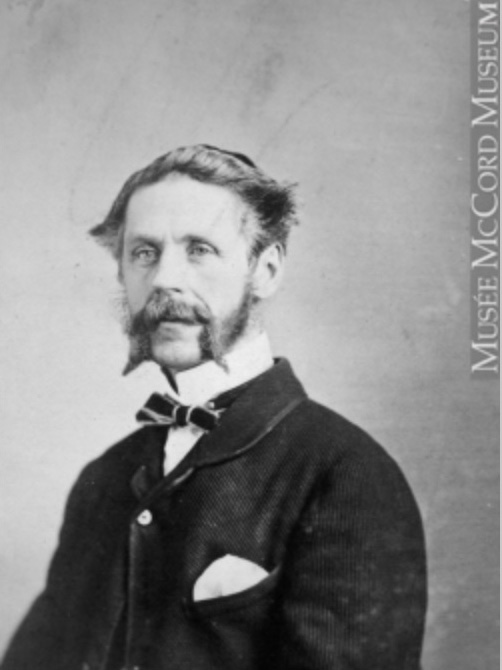

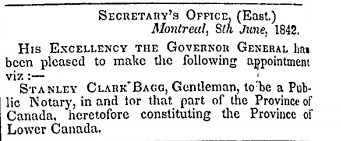

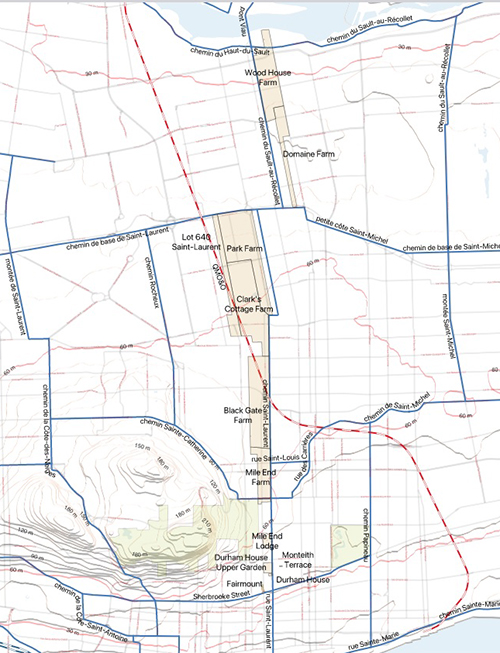

The estate at the heart of these problems was that of the late Stanley Clark Bagg (1820-1873), or SCB. He had owned extensive properties on the Island of Montreal. Several adjacent farms, including Mile End Farm and Clark Cottage Farm, stretched from around Sherbrooke Street, along the west side of Saint Lawrence Street (now Saint-Laurent Boulevard), while three other farms extended along the old country road, north to the Rivière des Prairies. SCB had inherited most of this land from his grandfather John Clark (1767-1827). Although he trained as a notary, SCB did not practise this profession for long, but made a living renting and selling these and other smaller properties.

At age 52, SCB suddenly died of typhoid. In his will, written in 1866, he named his wife, Catharine Mitcheson Bagg (1822-1914), as the main beneficiary of his estate, to use and enjoy for her lifetime, and then pass it on to their descendants. He also made her an executor, along with his son Robert Stanley Bagg (RSB, 1848-1912). There were two other executors: Montreal notary J.E.O. Labadie and his wife’s brother, Philadelphia lawyer McGregor J. Mitcheson.

But SCB’s estate was large and complicated, and no one was prepared to handle it. RSB had recently graduated in law from McGill and was continuing his studies in Europe at the time of his father’s death. As for Catharine, she became involved in decisions regarding property sales over the years, but she must have felt overwhelmed at first.

Notary J.A. Labadie spent two years doing an inventory of all of SCB’s properties, listing where they were located, their boundaries, and when and from whom they had been acquired, but he did not mention two key documents. One of these was the marriage contract between SCB’s parents, the other was John Clark’s will.

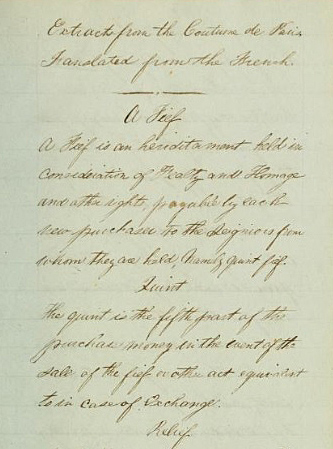

In the marriage contract, John Clark gave a wedding present to his daughter, Mary Ann Clark (1795-1835), and her husband, Stanley Bagg (1788-1853): a stone house and about 22 acres of land on Saint Lawrence Street. Clark named the property Durham House. But it was not a straight donation; it was a substitution, similar to a trust, to benefit three generations: Mary Ann’s and Stanley’s child (SCB), grandchildren (RSB and his four sisters) and the great-grandchildren. Each intervening generation was to have the use and income from the property, and was responsible for transmitting it to the next generation. That meant SCB could not bequeath it in his will because his children automatically gained possession, and so on, with the final recipients being the great-grandchildren.

In his 1825 will, Clark had made an even more restrictive condition regarding the Mile End Farm. This time the substitution was intended to be perpetual “unto the said Mary Ann Clark and unto her said heirs, issue of her said marriage and to their lawful heirs entailed forever.”

Perhaps Clark imposed these conditions on his descendants for sentimental reasons. Durham House was his daughter’s family home, and Stanley Bagg had probably courted Mary Ann on the Mile End Farm while he was running a tavern there with his father. Or maybe Clark simply believed that these provisions would give the best financial protection to his future descendants. SCB must have thought this was a good idea because his will also included a substitution of three generations.

Clark and SCB did not foresee, however, that the laws regarding inheritances would change. In fact, the provincial government changed the law regarding substitutions a few months after SCB wrote his will. This new law limited substitutions to two generations. Meanwhile, when SCB died in 1873, no one seems to have remembered that the substituted legacies Clark had created even existed.

Real estate sales practices also changed over the years. Clark had written a codicil specifying that any lot sales from the Mile End Lodge property, where he and his wife lived and which he left to her, were subject to a rente constituée. The buyer paid the vendor an amount once a year (usually 6% of the redemption value), but it was like a mortgage that could never be paid off. In the early 1800s this had been a common practice in Quebec, designed to provide funds to the seller’s family members for several generations.

SCB similarly stipulated that nothing on the Durham House property could be sold outright, but only by rente constituée. By the time he died, some of the properties located near the city outskirts were becoming attractive to speculators and to people wanting to build houses or businesses, but the inconvenience of a rente constituée was discouraging sales. It became clear that the executors had to resolve the issue.

They asked the provincial legislature to pass a special law. On February 23, 1875, the legislature assented to “An Act to authorize the Executors of the will of Stanley C. Bagg, Esq., late of the City of Montreal, to sell, exchange, alienate and convey certain Real Estate, charged with substitution in said will, and to invest the proceeds thereof.” (According to the Quebec Official Gazette, this was one of about 100 acts that received royal assent that day after having been passed in the legislative session to incorporate various companies and organizations, approve personal name changes, amend articles in the municipal and civil codes, etc.)

This act allowed the executors of the SCB estate, after obtaining authorization from a judge of the superior court, and in consultation with the curator to the substitution, to sell land outright, provided that the proceeds were reinvested in real estate or mortgages for the benefit of the estate. In other words, the rente constituée was no longer required, and sales previously made by the estate were considered valid.

No more changes were made until 1889, when family members realized that part of SCB’s property actually belonged to his children, and not to his estate, and a family dispute erupted. The story of how they resolved this issue and remained on good terms will be posted soon.

This article is also posted on the collaborative family history blog Genealogy Ensemble, https://genealogyensemble.com

Notes and Sources:

I could not have written this article without the help of urban historian Justin Bur. Justin has done a great deal of historical research on the Mile End neighbourhood of Montreal (around Saint-Laurent Blvd. and Mount Royal Ave.) and is a longtime member of the Mile End Memories/Memoire du Mile-End community history group (http://memoire.mile-end.qc.ca/en/). He is one of the authors of Dictionnaire historique du Plateau Mont-Royal (Montreal, Éditions Écosociété, 2017), along with Yves Desjardins, Jean-Claude Robert, Bernard Vallée and Joshua Wolfe. His most recent article about the Bagg family is La famille Bagg et le Mile End, published in Bulletin de la Société d’histoire du Plateau-Mont-Royal, Vol. 18, no. 3, Automne 2023.

Documents referenced:

Mile End Tavern lease, Jonathan Abraham Gray, n.p. no 2874, 17 October 1810

Marriage contract between Stanley Bagg and Mary Ann Clark, N.B. Doucet, n.p. no 6489, 5 August 1819/ reg. Montreal (Ouest) 66032

John Clark will, Henry Griffin, n.p. no 5989, 29 August 1825

Stanley Clark Bagg will, J.A. Labadie, n.p. no 15635, 7 July 1866

Stanley Clark Bagg inventory, J.A. Labadie, n.p. no 16733, 7 June 1875

Quebec legislation: 38 Vict. cap. XCIV, assented to 23 February 1875

See also:

Janice Hamilton, “Stanley Clark Bagg’s Early Years,” Writing Up the Ancestors, Jan. 8, 2020, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2020/01/stanley-clark-baggs-early-years.html

Janice Hamilton, “John Clark, 19th Century Real Estate Visionary,” Writing Up the Ancestors, May 22, 2019, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2019/05/john-clark-19th-century-real-estate.html