This month a Montreal tradition will resume after a two-year pandemic break: the annual St. Andrew’s Ball will take place at the Windsor Hotel on November 18. The event promises to be “a gala evening of dining, dancing and Scottish pageantry, celebrating Scottish heritage in Montreal,” featuring the Black Watch Pipes and Drums and highland dance performances.

My mother attended this event in 1937, the year that, despite her protests, she was a debutante. Writing under her married name, Joan Hamilton, she recalled that experience 40 years later, and her article, published in Montreal Scene magazine on November 26, 1977, described the endless social gatherings she and her teenage friends attended.

In those days “coming out” didn’t mean what it does today. Then, it meant that a young woman of 18 was introduced to society, and to members of the opposite sex, which was important because my mother and most of her friends attended separate private schools for girls or boys.

She wrote, “For a tightly-knit group of Montrealers whose growing up took place in the mid-30s, life consisted of a round of parties that started with events called sub-deb dances and progressed to coming-out balls. Actually, they weren’t as grand as they sound. Life was simpler then, and one lived by a strictly prescribed social code. The sub-deb parties were given at private homes, primarily during the Christmas holidays, and the ages of the future debutantes ranged from 14 to 17.” When the girls became debutantes, the parties became balls.

Although many Canadians were suffering economically during the Depression, my mother recalled that there were dozens of debutantes each season, and there was a ball at least once, and sometimes twice a week from October until February. Many debutantes came out at their own parties, but others were presented at either the St. Andrew’s Ball or charity balls put on by the Royal Victoria Hospital Auxiliary. At that time, most of the balls were held at the Winter Club on Drummond Street, the Hunt Club on Côte Ste-Catherine Road, or the ballroom of the Ritz-Carlton Hotel. The St. Andrew’s Ball took place at the Windsor Hotel.

In Montreal the St. Andrew’s Ball was first held in 1848, but some members of the society preferred a dinner for the men only, and the next ball wasn’t held until 1871. In 1878 it was described as “the social event of the year,” probably because Queen Victoria’s daughter Princess Louise and her husband were the guests of honour. Over the following years, however, Montreal’s Scots sometimes celebrated St. Andrew’s Day with a banquet or a concert, and the society did not choose a ball as its principal event until 1896.

According to the Montreal Daily Star, more than 900 people—a record—attended the 1937 edition of the St. Andrew’s Ball, including the Governor General of Canada and his wife, Lord and Lady Tweedsmuir. “Merriment reigns as sons and daughters of auld Scotia lay aside their cares,” the newspaper headline announced.

In the ‘30s, the debutantes wore long white evening dresses and white, elbow-length kid gloves, while their escorts were in white tie and tails. The evening began with dinner parties, with cocktails and wine served. On arriving at the ball, the guests went through a receiving line so the proud parents of the debutante in whose honour the party was being held could introduce her. Then the dancing began, with music provided by an orchestra. Supper was served around midnight, accompanied by champagne.

“One’s partner at dinner was supposed to, and usually did, have the first and last dance and escort you to supper, as well as take you home,” she recalled. “It was a good security blanket.” My mother was not one of those girls who was so popular with the boys that her dance card for the evening was always full. In fact, she hinted that she spent a fair amount of time in the ladies’ room, pretending to be invisible. Nevertheless, she wrote that her teen years were a lot of fun, going to movies, picnics and corn roasts in the summer and taking the train to the Laurentians to go skiing in winter, after the party season had wrapped up.

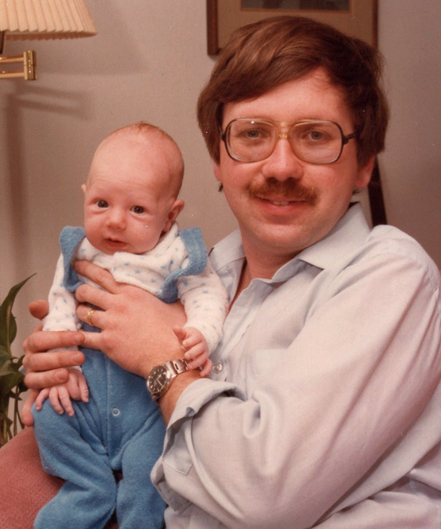

Two years later life changed for everyone, and some of the young men who had attended those parties went off to war and never came back. Nor did my mother marry one of the boys she was introduced to as a debutante; my parents met in Ottawa, where they were both working, just as the war was ending.

This article also appears on https://genealogyensemble.com.