My mother used to tell me that Amelia Norton was her favourite of her four great-aunts on her mother’s side of the family. From what I have learned about Amelia’s life, it appears she was indeed a kind and generous person.

Amelia Josephine Bagg was born in Montreal in 1852. Her father, Stanley Clark Bagg, was a wealthy landowner in Montreal, so Amelia had a privileged upbringing that included a year-long tour of Europe with the whole family in 1868-69, when she was 16.

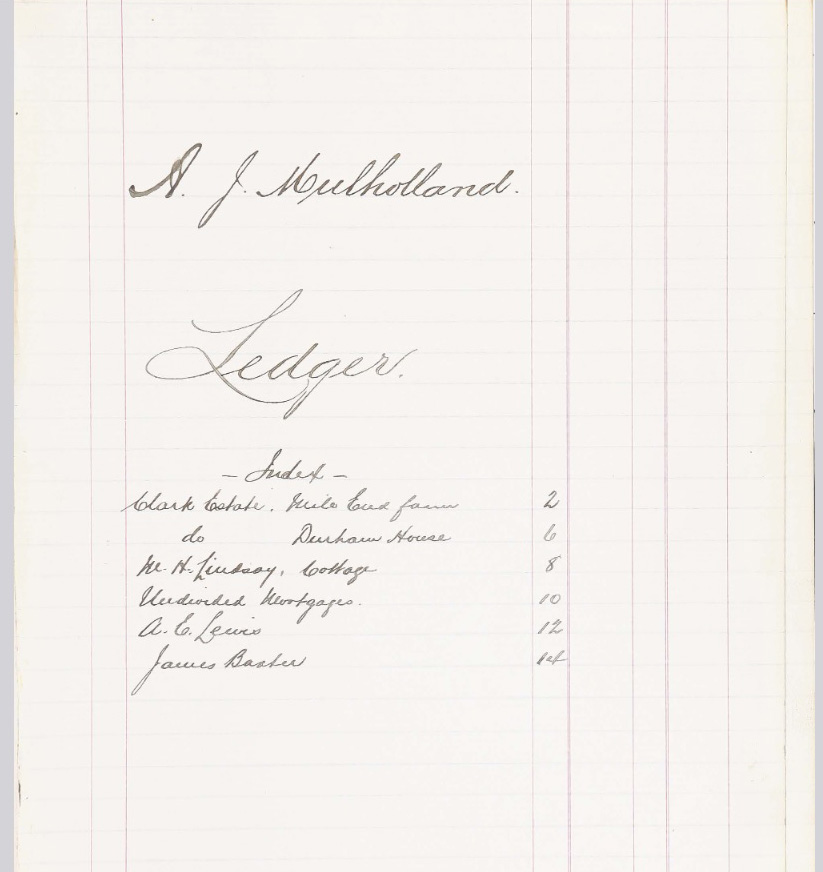

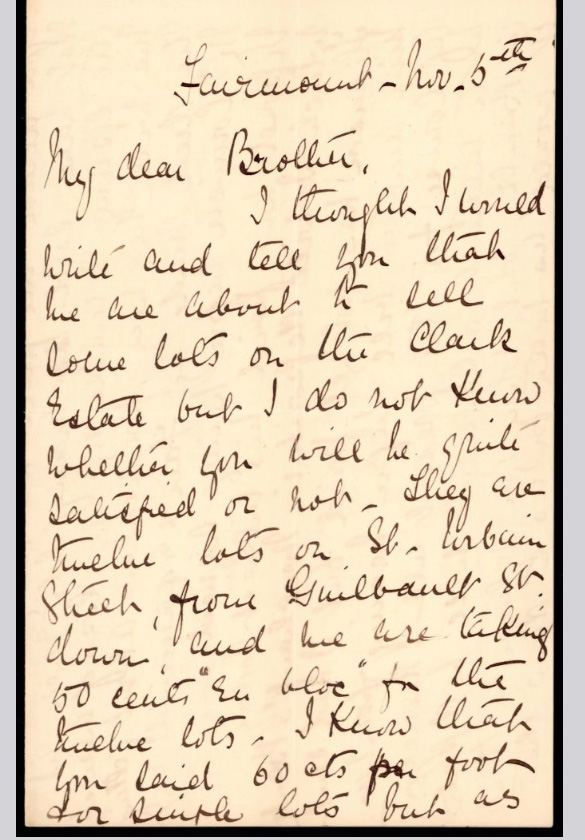

After her father died in 1873, her brother, Robert Stanley Bagg, took over management of their late father’s real estate, renting out some properties and selling others. Amelia had a strong interest in the Bagg family real estate business, helping to keep the records of sales, and she also owned property in her own name.

Amelia lived with her mother, Catharine Mitcheson Bagg, until she married at age 38. The wedding took place on Dec. 18, 1890 at Christ Church, Montreal’s largest Anglican church. Her husband was Joseph Mulholland, the eldest son of hardware merchant Henry Mulholland and his wife, Ann Workman. Born in Montreal in 1840, Joseph had a twin who died as an infant. Joseph is connected to me in two ways: in addition to being married to Amelia, his sister Jane Mulholland (1847-1938) and her husband, Montreal banker John Murray Smith (1838-1894), were my great-grandparents on my mother’s father’s side.

As a young man, Joseph had worked in the hardware business. Now, as Amelia’s husband, he started a new career in real estate. In 1891, he and his brother-in-law collaborated in a business venture: Joseph and John purchased a vacant piece of land from Robert Stanley Bagg on Saint Charles Borromée Street (now renamed Clark Street) near Pine Avenue and built a row of attached house there.1 The building, designed by architect Eric Mann, survives to this day.

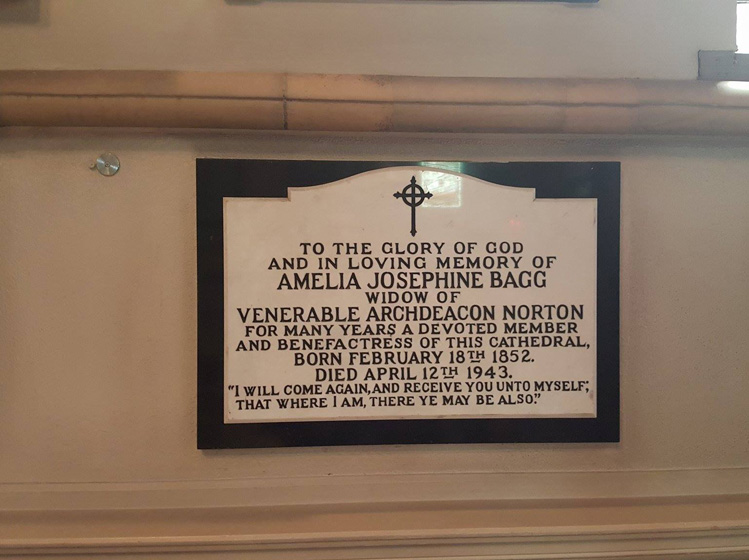

Joseph died, age 57, in 1897. Five years later, Amelia married again, this time to Reverend John George Norton, Archdeacon of Montreal.It was a relatively small wedding with only family members and a few close friends present.2 John was born in Ireland in 1840 and he was educated there. He moved to Montreal in 1884 with his wife and two children. His wife died five years later.

As the wife of one of the leading clerics in Montreal’s English-speaking community, Amelia took on a new role, especially in church charities. According to a biography of Archdeacon Norton in The Storied Province of Quebec, “Mrs. Norton is a lady of culture and refinement. Mrs. Norton was a valued ally and helpmate in all the parochial work of the church.”3

At that time, governments gave little funding to health care or social services, so benevolent societies played an essential role in society. As president of the Women’s Auxiliary of Christ Church Cathedral for many years, Amelia was especially interested in its missionary work.4 In addition, her name appeared regularly in lists of donors to various charities published in the local newspapers.

The couple lived in the church rectory for many years and after John retired, they moved into their own house on McTavish Street, near McGill University. When the Venerable John George Norton, Rector Emeritus and Archdeacon of Montreal John died in 1924 at the age of 84, many people attended his funeral service at Christ Church, where he had officiated for 37 years.

Meanwhile, Amelia seems to have been the go-to person when family members needed help. After Amelia’s Aunt Fanny (Mitcheson) Hague was widowed in 1915, Fanny came to live with the Nortons and remained there until she died in 1919.

My grandparents also went to Amelia for help. They had built a new house just before the Depression hit and my grandfather lost his job. Amelia helped to support the family until my grandfather found a new job after the Depression.

Amelia died in 1943, at age 91, at home on McTavish Street, following a long illness. She is buried with her first husband in the Mulholland-Workman family plot in Montreal’s Mount Royal Cemetery.5

Sources

- Le Prix Courant: le journal de commerce, 10 Avril 1891, p 13, https://numerique.banq.qc.ca, entry for John Murray Smith, https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/2746357?docsearchtext=%22John%20Murray%20Smith%22, accessed June 18, 2023.

- “Marriage at the Cathedral”, The Gazette, 25 June, 1902, p. 6, Newspapers.com, accessed June 18, 2023.

- William Wood, editor, The Storied Province of Quebec, Past and Present, Dominion Publishing Company, 1931, vol. 3, p. 118.

- “Obituary: Mrs. J. Norton, 91, Dies at Home Here,” The Gazette, April 13, 1943, p. 14, Newspapers.com, entry for Amelia Norton, accessed June 20. 2023.

5. Mount Royal Cemetery, section F200-c

See also

Frank Dawson Adams, A History of Christ Church Cathedral, Montreal, Montreal: Burton’s Limited, 1941, https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/2561503

Janice Hamilton, “Continental Notes for Public Circulation”, April 8, 2020, Writing Up the Ancestors, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2020/04/continental-notes-for-public-circulation.html

Janice Hamilton, “Aunt Amelia’s Ledger”, April 26, 2023, Writing Up the Ancestors, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2023/04/aunt-amelias-ledger.html

Janice Hamilton, “Henry Mulholland, Montreal Hardware Merchant”, March 17, 2016, Writing Up the Ancestors, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2016/03/henry-mulholland-montreal-hardware.html

Janice Hamilton, “The World of Mrs. Murray Smith”, Feb.24, 2016, Writing Up the Ancestors, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2016/02/the-small-world-of-mrs-murray-smith.html

Janice Hamilton, “Never Too Late for Love,” April 4, 2014. Writing Up the Ancestors, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2014/04/never-too-late-for-love.html

This article is also posted on https://genealogyensemble.com