A probable distant relative contacted me recently, saying that she had come across the will of our common ancestor Alexander Tocher (1754-1844) on the Scotland’s People website. She found it too difficult to transcribe, so I cheerfully offered to try. Little did I know what would be involved!

The handwriting is quite clear since the document was written by a court clerk, nevertheless, numerous words were hard to decipher. The unfamiliar terminology related to Scottish inheritance laws and land ownership proved the biggest challenge, and some complex sentences seemed to go on forever.

Still, I hoped this document would reveal more details about Alexander and his family. I already knew something about the Tochers, based on an outline of the family’s history compiled by an unidentified family member many years ago and verified by my own research, including a visit to the Tocher grave in Scotland.

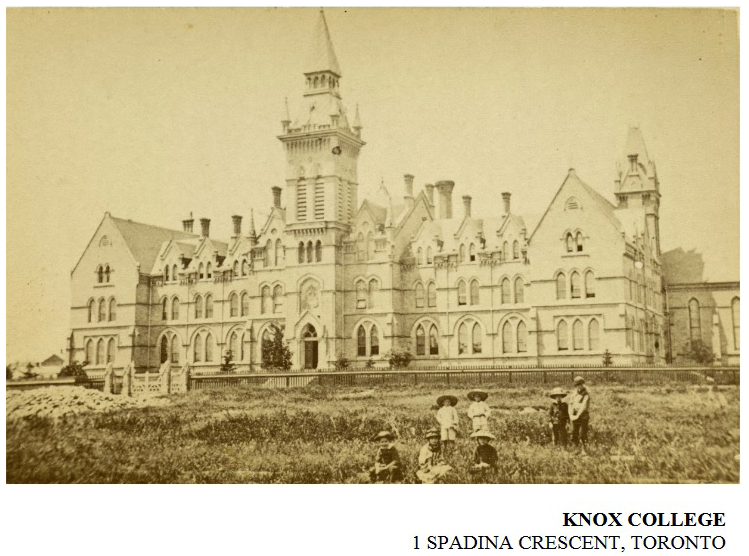

The monument reads: “Erected by the family in memory of their mother Jane Tocher, wife of James Smith, sometime schoolmaster in Macduff, d. 28 Feb. 1838 aged 35. Also her daus. Elizabeth aged 3 and Mary aged 2 and their son Alexander d. Toronto, Canada 18 Sept. 1855 aged 32. Also Alexander Tocher for 67 years schoolmaster in Macduff d. 10 Feb. 1844 aged 89 and his [second] wife Ann Haslopp d. 3 Jan. 1850 aged 83. The above James Smith late tutor Knox College, Toronto, Canada d. there 3 Jan 1867 aged 66.”

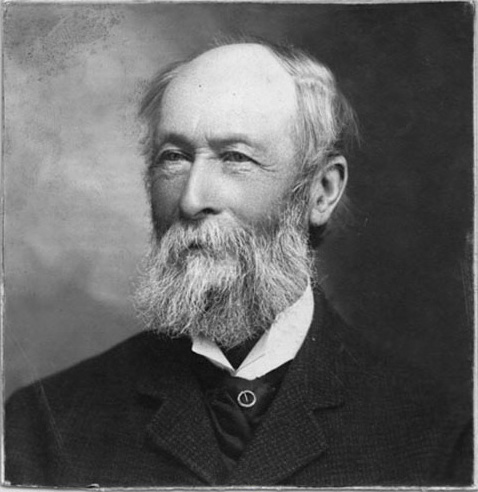

Parish records show that Alexander was born in Grange Parish, Banffshire, Scotland, where his father was a miller at Paithnick.1 After graduating from the University of Aberdeen in 1779,2 Alexander became a teacher in MacDuff, a market town with a harbour on the Firth of Moray. He taught there for 67 years.3 Alexander married Elizabeth Stephen in 17984 and they had three daughters, Margaret, Elizabeth and Jane. After his wife died in 1805, he married Ann Haslopp. He died on February 10, 1844, age 89.5 By that time, Jane (1803-1838, my great-great-grandmother), had died6 and his son-in-law was probably considering moving the family to Canada.

What Was in Alexander’s Will?

Some of my ancestors left quite personal wills, affirming their faith in God or expressing regrets for things they had done in life. Not so Alexander. This document is an inventory of his moveable property and a Disposition and Deed of Settlement from the Banff Sheriff’s Court.

The first section of the document was housekeeping: it noted the date of his death and the value of his moveable property, and it noted that his daughter Elizabeth was the executor of the will. (According to the 1841 census of Scotland, the unmarried Elizabeth lived with him and his wife on Duff Street in Macduff.)

The inventory of Alexander’s moveable property indicated that he probably lived quite comfortably. Among his possessions were a portable writing desk, a dozen silver spoons, an eight-day clock, two feather beds, and two tea kettles, four pots and an oven. His most valuable possession was a branded cow with no horns. The total value of the inventory was 33 pounds, 12 shillings and eight pence.

Alexander mentioned his two sons-in-law in his will. He noted that he had loaned 200 pounds at four percent interest to Margaret’s husband, merchant Alexander Carny. It had not yet been repaid, and he directed his executor to forgive 180 pounds. Similarly, he had loaned 170 pounds to Jane’s husband, teacher James Smith, and he directed that debt be discharged.

Other than this, Alexander’s will did not mention family members, probably because Scotland had clear rules about who was to inherit. Heritable property (land and buildings) was to go the eldest son, while wives and all children had equal rights to moveable property.

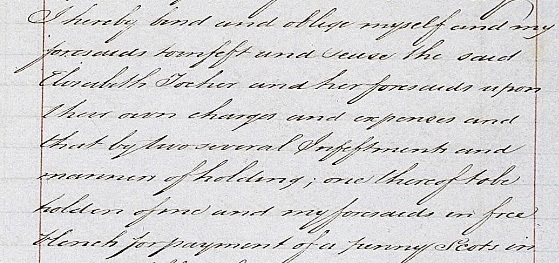

This excerpt of Alexander’s will reads: “I hereby bind and oblige myself and my foresaids to infeuff? and ? the said Elizabeth Tocher and her foresaids upon their own charges and expenses and that by two several? infeffments and manners of holding, one thereof to be holden of me and my foresaids in free ? for payment of a penny Scots in ….. ”

image source: www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk

Alexander’s Property in Macduff

The most extensive part of the will concerned his real estate: four tiny pieces of land in the town of Macduff. He had acquired them at different times, perhaps with the intention of consolidating them and building a house. He left these lots in Elizabeth’s hands.

The fact that he had any land was a surprise. The vast majority of Scots were tenants.

According to the Statistical Accounts of Scotland, 1834-1845, the Earl of Fife held almost half the land in Gamrie, the parish in which Macduff was located. In fact, the system of land ownership in Scotland was still a feudal one. Technically, Alexander was not a landowner, but a feuar: a vassal who paid annual dues for the right to use the land.

After transcribing five of the will’s six pages – including lots of question marks and blank spaces — I gave up, but by then I had learned a lot about my ancestors’ lives in 19th century Scotland.

Sources

- Scotland, “Search Old Parish Registers (OPR) Births/Christenings (1553-1854),” database, ScotlandsPeople,www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk : accessed 24 March, 2012, entry for Alexander Tocher, baptism, 28 July, 1754, Grange Parish Banff.)

- Peter John Anderson, Officers and Graduates of University and King’s College Aberdeen, 1495-1855; Aberdeen: Printed for New Spalding Club, 1893; https://archive.org/stream/officersgraduate00univuoft#page/254/mode/2up, accessed Nov. 19, 2017.

- Monument Inscription, Doune Kirkyard, Macduff. Viewed personally, 1 June, 2012.

- Scotland, “Search Old Parish Registers (OPR) Marriages,” database, ScotlandsPeople (www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk : accessed 15 February 2015, entry for Alexander Tocher, 17 November, 1798, Gamrie and MacDuff.)

- Scotland, “Search Wills and Testments, 1513-1925,” database, ScotlandsPeople (www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk : accessed Nov. 19, 2017, entry for Alexander Tocher, 8 January, 1845.

- Monument Inscription, Doune Kirkyard.

See also:

Janice Hamilton. “My Tocher Family,” Writing Up the Ancestors, Feb. 13, 2015, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2015/02/my-tocher-family.html

Notes: The following sources provide background on Scottish wills and testaments:

National Records of Scotland, Scotland’s People (www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk) Guides — Wills and Testaments, accessed Nov. 19, 2017, https://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/guides/wills-and-testaments#Background%20information

Chris Paton, Discover Scottish Land Records, Unlock the Past; Milton, Ontario: Global Genealogy, 2014.