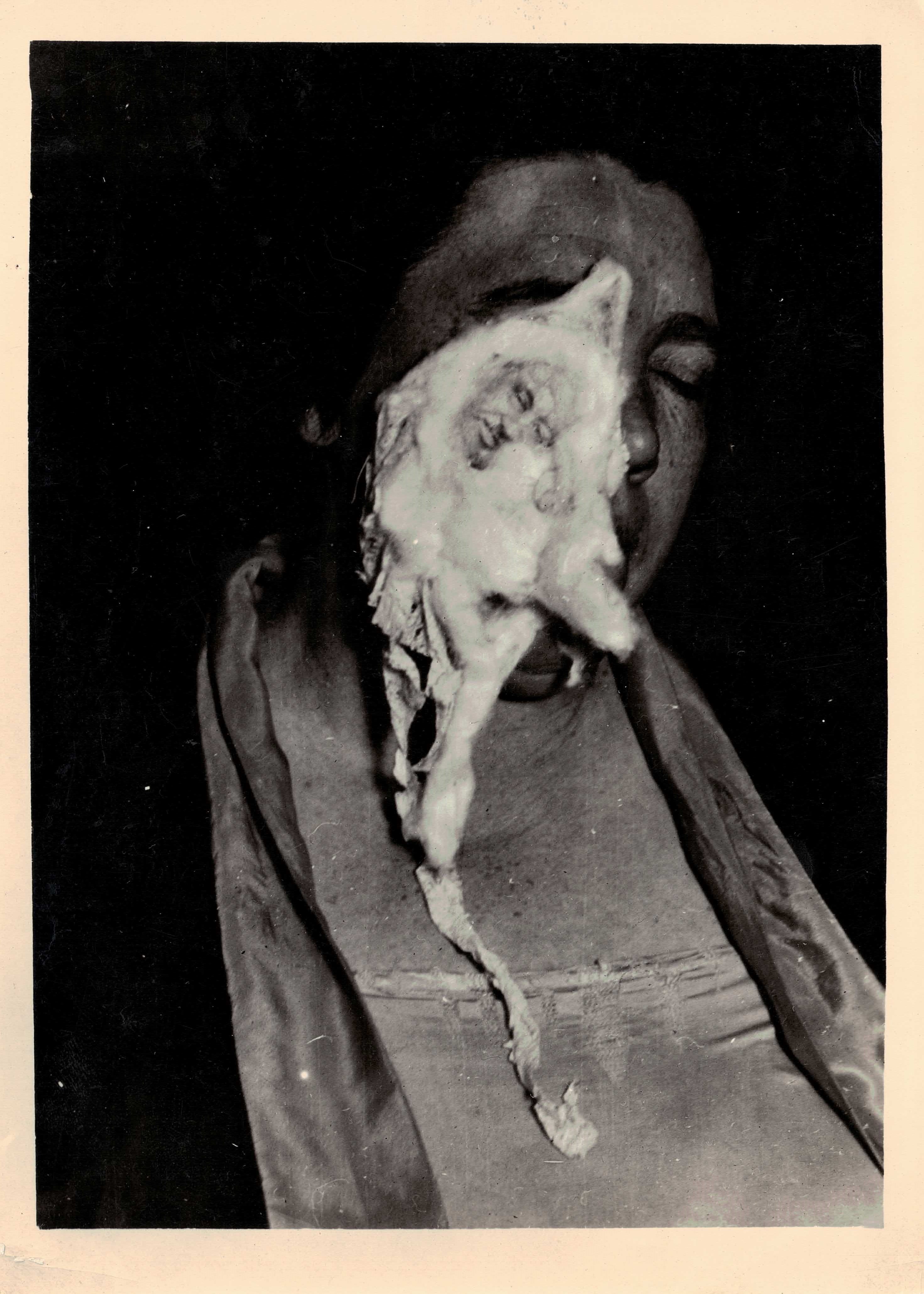

When I was a teenager, I came across a book in my parents’ house called Intention and Survival, written by T. Glen Hamilton, my grandfather. Inside a plain beige cover, the text was illustrated with grainy black and white photographs. Many of them showed a middle-aged woman, her eyes closed, with a white substance coming from her mouth or nostrils. Tiny images of the faces of deceased individuals seemed to be embedded in this substance.

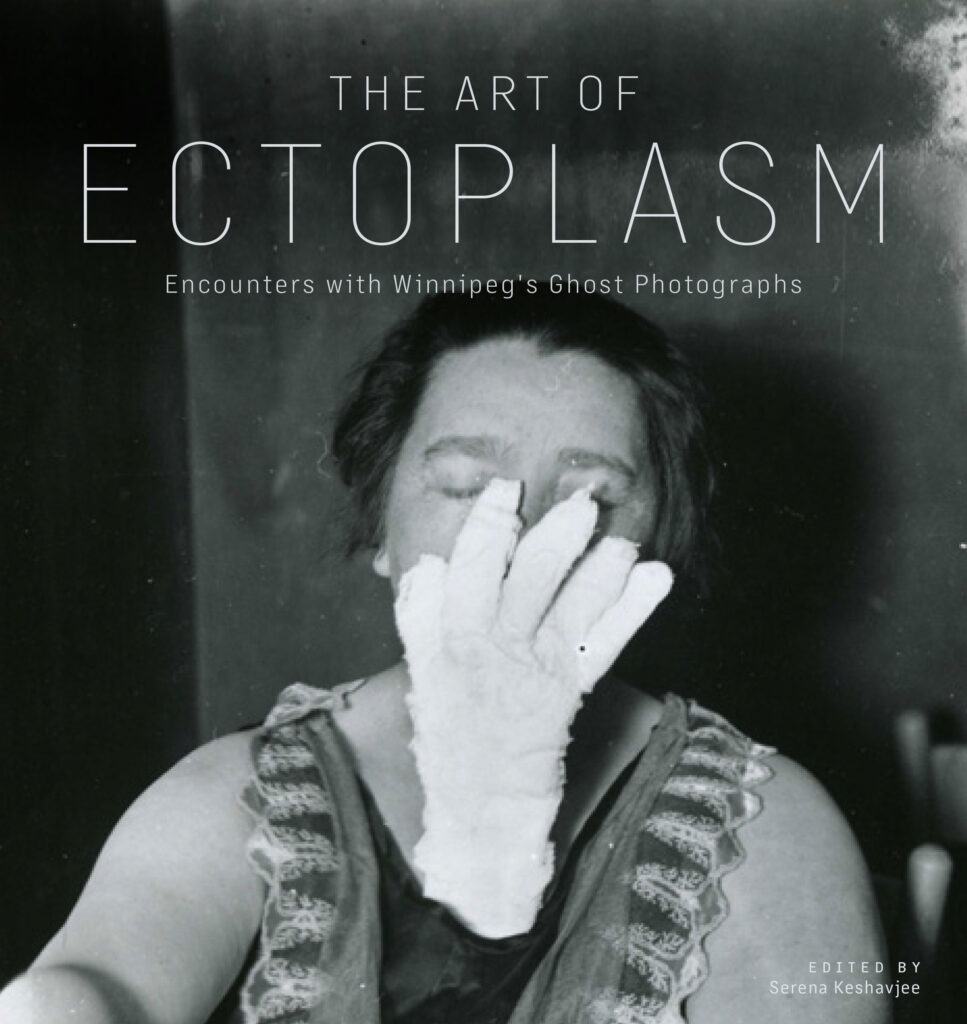

Those photos gave me nightmares, and for decades, I have been trying to figure out what to make of them. Now, a new book called The Art of Ectoplasm: Encounters with Winnipeg’s Ghost Photographs is helping me understand them.

Edited by Serena Keshavjee, a professor of art and architectural history at the University of Winnipeg, and published by the University of Manitoba Press, The Art of Ectoplasm looks at the context in which my grandparents researched and photographed psychic phenomena, including that white substance called ectoplasm. The book describes their work and the many artistic projects it has inspired.

Published on large-format paper, the book itself is a work of art. The black and white, sepia and contemporary colour photographs almost glow. Most of the old photos were taken during séances held at the Hamiltons’ Winnipeg, Manitoba home 100 years ago. Shot in a darkened room, lit by flash, with large-format cameras, these are sharp, high-contrast images that can be seen as both documentary photos and as art. Meanwhile, the 300-page text explores the history of these séances and includes an extensive bibliography. Dr. Thomas Glendenning Hamilton (1879-1935), known to most of his friends as T.G., was a family physician and surgeon, president of the Manitoba Medical Association and member of the Manitoba Legislative Assembly. He was a strict Presbyterian and elder of his church. He and his wife, Lillian (Forrester) Hamilton (1880-1956), had four children, including twin boys. Everyone in the household got sick during the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic, and one of the twins, three-year-old Arthur, died of the flu.

At the time, many people were strongly religious and believed in personal survival after death. Some tried to communicate with deceased loved ones. Although T.G.’s experiments in telepathy date from 1918, before the influenza pandemic, Arthur’s death may have stimulated the Hamiltons’ interest in the psychic field. Lillian started experimenting with table movements and rapping, and eventually T.G. was encouraged to participate. He decided to take a scientific approach. He prepared a room in the family home where the conditions could be carefully controlled and, in 1923, he began to conduct a series of experiments related to telekinesis, trance and mediumship that included the appearance of ectoplasm. These séances took place once or twice a week over a twelve-year span.

Lillian encouraged and collaborated with her husband, conducted research to make sense of alleged trance communications, did much of the organizing and often chaperoned the mediums. After T.G.’s death, she compiled the notes taken during the séances, as well as the photographs, her husband’s speeches and other material. She also continued to attend séances. She has received little public credit for her contributions, but that is beginning to change as Katie Oates, of Western University in London, Ontario, contributed a chapter in this book that focuses on Lillian’s role.

In 1979, T.G. and Lillian’s daughter, Margaret Hamilton Bach (1909-1986), donated the original photographic glass negatives and documents to the archives at the University of Manitoba. Since then, the university has received many other collections of material related to psychical research and, as archivist Brian Hubner writes in The Art of Ectoplasm, the city has become known as “weird Winnipeg, an unlikely centre of the paranormal”.

Shelley Sweeney, archivist emerita and retired head of the University of Manitoba Archives and Special Collections, notes that the Hamilton Family Fonds has inspired a variety of projects, including books, plays and visual arts. It is the most utilized collection of personal records held by the archives, and photographs from the Hamilton collection have been exhibited in museums around the world.

In another article, Esyllt W. Jones, a professor of history and community health sciences at the University of Manitoba, puts the Hamiltons’ séances into the context of the couple’s grief following their child’s death. She also shows how their experience was an example of the trauma caused by the pandemic and the loss of loved ones during World War I.

Thanks to the movie Ghostbusters, the word ectoplasm became popular in the 1980s, long after T.G.’s research involving ectoplasm took place between 1928 and 1934. Ectoplasm has been described as a vaporous substance that appears from the mouth or other orifices of a medium. Formless at first, it can change to resemble muslin or cotton batting before being reabsorbed into the medium’s body. T.G. thought of it as a living thing, directed by an internal intelligence. Ectoplasm has not been tested in a laboratory and, since World War II, it has not been considered a topic for credible scientific study.

The scientific methods that T.G. used in his “laboratory” are outdated today, but during his lifetime, as editor and contributor Keshavjee writes, psychical research was considered within the bounds of accepted scientific inquiry. There was a large body of literature on the topic and a number of well-respected scientists of the era accepted that strange things happened in the séance room. But, Keshavjee suggests, when the Hamilton séance activities began to be directed by an unseen personality called Walter, T.G.’s claims that he followed scientific methods lost credibility.

Today, questions about fraud hang over many psychic activities. Some people are convinced the Hamilton séances were fraudulent, others believe they were genuine. For the most part, this book accepts the Hamilton séance photographs without trying to address the issue.

In his chapter defending the Hamilton family psychical research legacy, Walter Meyer zu Erpen, founder of the Survival Research Institute of Canada and an archivist who has spent more than 30 years investigating these events and the people involved, concludes that the ectoplasm photographed by the Hamiltons was genuine.

Whether the appearance of ectoplasm was proof of survival after death is another question. In general, Keshavjee writes, there is little basis for belief that psychic phenomena inherently provide evidence of life after death. Meyer zu Erpen admits he is taking a middle-of-the-road position when he suggests that, in the Hamilton séances, only the ectoplasm samples with miniature faces of the deceased contribute to evidence for survival of human personality beyond death.

T.G. was convinced, however, that what he experienced in the séance room could only be the work of surviving spirts. For him, and for Lillian, survival was a fact.

The Art of Ectoplasm did not answer all my concerns, but for anyone interested in the Hamilton séances from an artistic, historical or psychical research perspective, it is worth going beyond the amazing photos and reading the text.

This post also appears on the collaborative family history blog https://genealogyensemble.com

Notes:

Full disclosure: as family historian, my research has been quoted several times in The Art of Ectoplasm, and my father edited Intention and Survival.

The Art of Ectoplasm is available from the University of Manitoba Press, https://uofmpress.ca/books. It can also be ordered from Amazon, Indigo and other booksellers.

See also:

Hamilton Family Fonds, University of Manitoba, UM Digital Collections, Archives and Special Collections, https://digitalcollections.lib.umanitoba.ca/islandora/object/uofm%3Ahamilton_family

Walter Meyer zu Erpen, “Hamilton, Thomas Glendenning” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hamilton_thomas_glendenning_16E.html

Janice Hamilton, “Reinventing Themselves Has Been Launched”, Writing Up the Ancestors, June 23, 2021, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2021/06/reinventing-themselves-has-been-launched.html