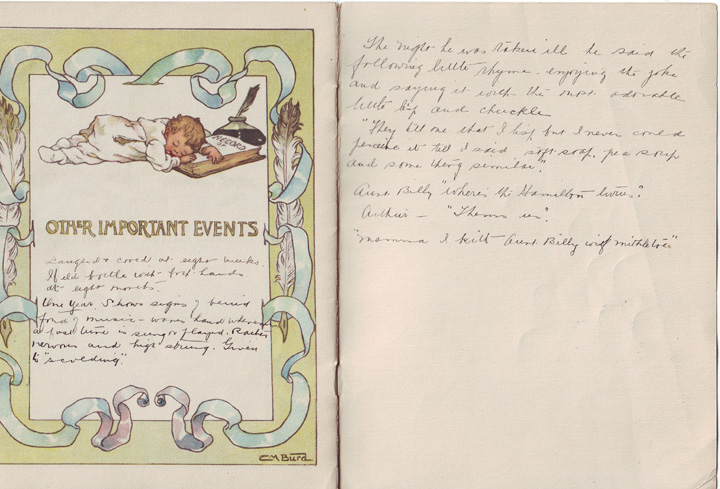

The night before three-year-old Arthur Hamilton became ill, he was reciting a rhyme and joking about lisps and kisses and mistletoe with a family friend who was helping put the children to bed. Someone – his mother or the friend – recorded those words in his baby book.

The following day, Arthur came down influenza. In fact, everyone in the house – his parents, his twin brother and his two older siblings – got sick. The others recovered, but Arthur did not.

When the influenza pandemic reached the Hamiltons’ Winnipeg home in January 1919, it was at its deadly peak. Arthur was among more than 1,200 Winnipeg residents and 50,000 Canadians killed by the pandemic, which was brought to Canada by troops returning from the trenches of World War I.1 Some 21 million people died from the virus worldwide.

Today, Arthur’s baby book, and that of his twin (my father,) is in the University of Manitoba Archives as part of the Hamilton Family collection. These cheerfully illustrated booklets include important milestones, such as the twins’ first steps. Arthur’s book is especially moving because of the entry about the jokes he made just before he became ill.2

Archivist Shelley Sweeney has used Arthur’s baby book in the classroom many times. For example, she took it to a religious studies class that was exploring how people react to death by expressing regret and memorializing the person who has passed.

“It strikes people as so unbearably sad,” she says. “There are always sympathetic expressions and murmurs when I talk about it.”3

The death of a young child like Arthur seems especially sad, but the influenza pandemic traumatized whole communities. Some people lost family members to the flu after having already lost sons and brothers in the war. Many of those who died were between 20 and 40 years old, in the prime of their lives. Children were left without parents, families without income earners, businesses without customers, and manufacturers without workers. Poor neighbourhoods had the highest death rates.

Some people compared the pandemic to the Black Death of medieval times. The government banned large public gatherings to try to control the spread of the virus. Hospitals and physicians were overwhelmed. My grandfather was a physician and my grandmother had trained as a nurse, but they couldn’t save their son. They tried everything they knew, but there were no effective treatments in 1919.

Their older son, Glen, a future a physician himself, later recalled being taken in to see Arthur’s body. He said, “I can remember on the floor beside his crib there was an enamel basin with boiling water in it – Friars Balsam [eucalyptus oil] – that aromatic stuff you put into body rub, and a little tank of oxygen. And those were the weapons to fight the flu. That was all!”4

My grandfather, Thomas Glendenning (T.G.) Hamilton, was devastated by his son’s death. Not only had he failed as a physician, but, as Glen Hamilton suggested in an interview, T.G. may have felt that he had been too attached to Arthur. “Dad was a very strict Calvinist Presbyterian and he felt that in some way, because he was so fond Arthur …. that he was being punished by the Lord ….” 5

Arthur’s death was a pivotal event for the Hamiltons in a way that seems surprising today, but was typical for the time. Many people were deeply religious and believed in personal survival after death. Grieving families wanted to communicate with loved ones who had passed, so they turned to mediums and séances. Between the two world wars, a strong spiritualist movement developed in Canada and elsewhere.6 Glen suggested that Arthur’s death stimulated his parents’ interest in the psychic field.

What made the Hamiltons unusual was the effort they put into exploring psychic phenomena. For more than 10 years, until T.G.’s death in 1935, they held almost weekly séances with a small group of regular participants.7T.G. became known across Canada, the United States and England for his psychic research, while Lillian played a key organizing role in the background. T.G. emphasized the “scientific” nature of his enquiry, but his grief must have coloured these experiences.

Around 1980, Margaret (Hamilton) Bach donated her parents’ research notes, speeches and photographs to the University of Manitoba Archives, and a few years ago I added a few items, including the twins’ baby books. Today, many people consult the Hamilton Family fonds. Some are interested in psychics, several have used the collection as inspiration for plays and visual art, and other researchers are using the collection to explore how people cope with trauma.

Although many people, including myself, are skeptical about the authenticity of their experiments, it is wonderful to see that T.G.’s and Lillian’s passion is still contagious in so many different ways.

This story is also posted on https://genealogyensemble.com

Notes and Sources

T.G. Hamilton and Lillian (Forrrester) Hamilton had four children: Margaret Lillian (1909-1986), Glen Forrester (1911-1988), and twins James Drummond (1915-1980) – my father — and Arthur Lamont (1915-1919). To read more about the Hamilton Family fonds, see http://umanitoba.ca/libraries/units/archives/digital/hamilton/index.html

- Janice Dickin, Patricia G. Bailey, “Influenza”, The Canadian Encyclopedia, Historica Canada, http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/influenza/(accessed March 20, 2017).

- Baby book of Arthur Lamont Hamilton. University of Manitoba Archives and Special Collections (UMASC), Hamilton Family fond, A10-01, Winnipeg.

- Personal email communication with Shelley Sweeney, March 23, 2017.

- James B. Nickels. “Psychic Research in a Winnipeg Family: Reminiscences of Dr. Glen F. Hamilton”, Manitoba History, June 2007, p. 53.

- Ibid.

- Esyllt Jones, “Spectral Influenza: Winnipeg’s Hamilton Family, Interwar Spiritualism and Pandemic Disease,” in Magda Fahrni and Esyllt W. Jones, editors, Epidemic Encounters: Influenza, Society and Culture in Canada, 1918-20, Vancouver: UBC Press, 2012, p. 195.

- Janice Hamilton “Bring on Your Ghosts!” Paranormal Review, winter 2016, p. 6. This magazine is published by The Society for Psychical Research in England. This edition is entirely devoted to the psychic research carried out by the Hamiltons.