My passion for genealogy, my interest in maps and the enjoyment I get from painting and drawing become even more fun when they intersect with each other.

I have been taking art classes for many years, and my ancestors sometimes turn up in my paintings in some manner or other. Maps are another frequent theme in my artwork, sometimes just as a layer that I cover with paint, sometimes as an image of a place or a route from one place to another. Sometimes I use street grids or contour lines as the starting-point for a drawing, and a birds-eye view of landforms can inspire me to create an abstract image.

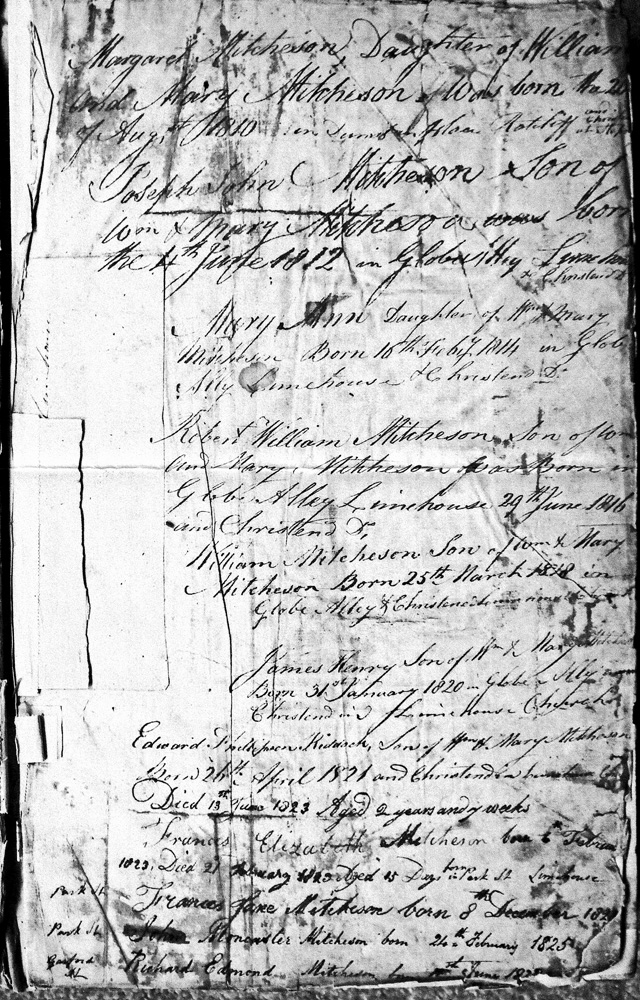

A few years ago, I collected images that were associated with my great-great grandmother Catharine Mitcheson Bagg and put them together in a collage. I included a photograph of a portrait of her; a hand-painted photograph of Fairmount Villa, the house where she lived in Montreal, a letter she wrote and a painting she did on the outskirts of Philadelphia, where she grew up. I glued all these elements on top of some maps of the area where she lived in Montreal. I found these maps on the website of the Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec, I enlarged and printed several sections, coloured them and then covered them with thin rice paper.

I love old maps, not only because they can be beautiful. Some show places that no longer exist, or that have been swallowed up by urban centers. They can show political boundaries that have changed over time, land use patterns, railway lines that have disappeared, and the locations of church buildings that are now used for entirely different purposes. That makes them an essential research tool for tracking family history.

Family records said my great-great-grandmother Janet MacFarlane was born in Dunkeld, Scotland, and a handwritten note suggested she was born in Craig O’Gowrie, Perthshire. Other notes said Janet’s father was a stonemason before the family left for Canada in 1833, and the family lived near the Tay River.

These were all important clues, but it turned out they were not entirely accurate. Parish records showed that Janet was baptized in Clunie Parish, Perthshire, which is near the Tay and not far from Dunkeld. Frustratingly, I could not find a place called Craig O’Gowrie anywhere.

I searched a number of old maps on the National Library of Scotland’s website and discovered several hamlets called Gourdie in Clunie Parish, including Craigend of Gourdie. When one map showed there had been quarries nearby, I concluded the family had probably lived there.

I recently participated in a workshop on art and cartography. Our instructor sent us to the park across the street to map, not what we saw, but what we heard: birds, cars, people walking by, someone raking, a loud machine that didn’t stop. That workshop has inspired me to broaden my thinking about the ways maps can represent reality and social history, and to find new ways to make maps into art.

Image sources:

Collage by Janice Hamilton. “Catharine Mitcheson Bagg,” 1865, by William Sawyer, National Gallery of Canada (no. 26744).

Knox, James. “Map of the Basin of the Tay, including the Greater Part of Perth Shire, Strathmore and the Braes of Angus or Forfar.” Edinburgh: W. & A. K. Johnston, 1850. N. pag. National Library of Scotland. Web. 19 May 2015.