In 1878, two brothers from Montreal opened a hardware store in Winnipeg, Manitoba. The Prairie city, known as the “gateway to the west,” was growing rapidly, and for several years the store appears to have been profitable, however, it went bankrupt in 1889. After that, the brothers’ lives took very different paths.

Mulholland Bros. Hardware Merchants was owned by Joseph Mulholland (1840-1897) and his younger brother Henry (1850-1934). Hardware must have been an easy choice for them since their father and several of their uncles had been very successful in the hardware business.

Their father, Henry Mulholland (1809-1887), was born in Lisburn,1 near Belfast in the north of Ireland, and immigrated to Montreal as a young man. He soon found employment with a wholesale and retail hardware firm owned by Benjamin Brewster. By 1851 he was a partner in the Brewster and Mulholland hardware company. He later went into partnership with a member of the extended Workman family, Joel C. Baker. The hardware firm of Mulholland and Baker was in business from 1859 to 1879.

Henry Mulholland sr. married Ann Workman (1809-1882) in Montreal in 1834. The Workman family had also come from the Lisburn area. Four of Ann’s brothers were in the hardware business, including William Workman (1807-1878) and Thomas Workman (1813-1889),who were partners in the firm of Frothingham and Workman, reputed to be the largest wholesale hardware company in Canada. The country’s population was growing, and hardware and building materials were in great demand.

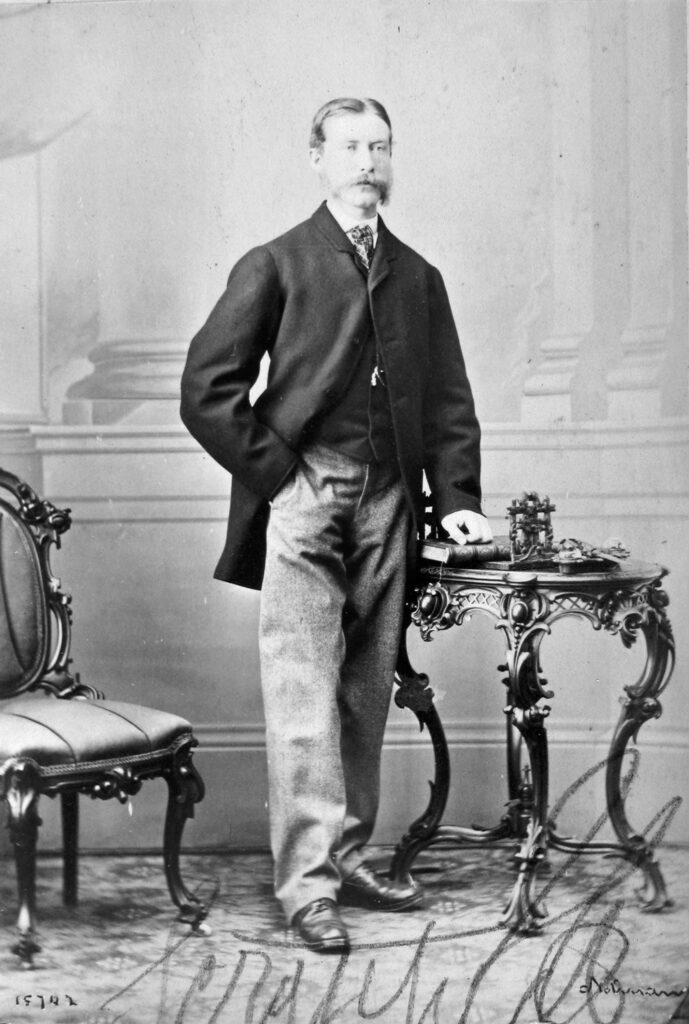

Henry and Ann Mulholland had several children who died very young, but two daughters (Ann and Jane) and three sons (Joseph, Henry and Benjamin) lived to adulthood. Both daughters remained in Montreal. Ann married Dr. George Henry Wilkins, while Jane and her husband, banker John Murray Smith, were my great-grandparents. Son Benjamin died of tuberculosis in Toronto in 1882.

The 1870 Canadian census found Joseph, 29, and Henry, 19, living in Montreal with their parents. Joseph was identified as a merchant, probably employed by his father’s firm. According to one newspaper account, he lived in Guelph, Ontario for a time prior to going to Winnipeg.2 Henry also worked for the family-owned hardware companies at the beginning of his career. Then, in 1878, Joseph and Henry headed to Manitoba. Many families were doing the same thing, attracted by the vast expanses of prairie farmland

The city of Winnipeg, incorporated in 1873, was a service center for the surrounding grain farms and, about a decade later, it became an important stop on the newly built Canadian Pacific Railway. The first CPR train steamed into the city in 1886. Optimists envisioned Winnipeg as a future “Chicago of the North”. In 1873, the city had a population of about 1900 people; that had risen to 8000 by 1881 and 42,000 in 1901.

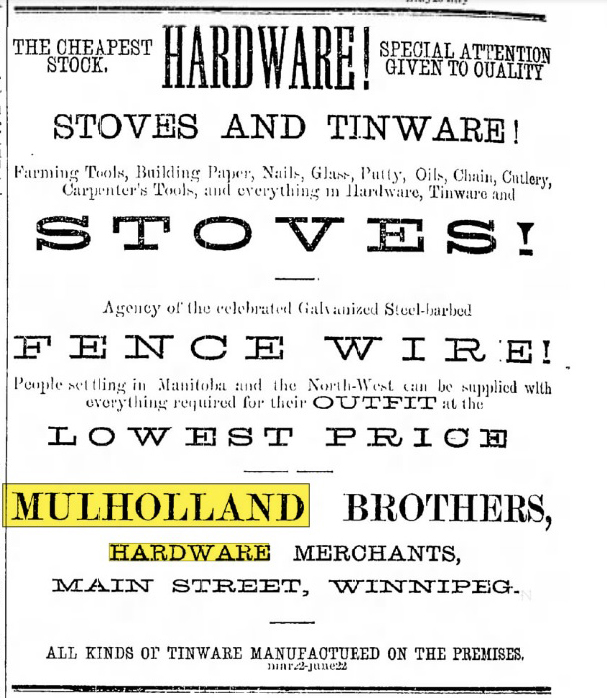

When Joseph and Henry opened their Winnipeg store in 1878, it faced stiff competition, and the large newspaper advertisement announcing the opening of Mulholland Bros. ran alongside ads from several other hardware stores. Over the next few years, the newcomers focused on basic items like fencing wire and wood stoves.

Running a business with a sibling had its challenges. In a letter to his father in 1884, Henry must have mentioned that he and Joseph did not see eye to eye on a bookkeeping entry. Henry senior replied, “Joseph is a good-hearted, generous fellow, and I trust that you and he will get on cordially together, as it will be for your natural interest to continue the business without any wrangling and refer any differences of opinion between you and him to your Uncle Thomas [Workman] and me who have had long experience in co-partnership businesses and in keeping accounts between the copartners.”3

Henry senior continued to offer sensible advice and encouragement: “I am glad to hear that you are making no bad debts and that you have no large accounts due to you in the books and that your stock is well selected and next to this never be tempted to offer any customer to increase his indebtedness by selling him more goods on credit in hope of obtaining payment of a past due debt.”

It appears that Joseph was the more outgoing sibling. His name appeared frequently in Winnipeg newspapers as he was involved with the Board of Trade. He was for a time president of the Winnipeg Liberal-Conservative Association, and he was briefly a candidate for mayor of Winnipeg, but withdrew his name. Several newspaper clippings following his death described him as a very likeable fellow.

Meanwhile, Henry’s name never appeared in the newspapers, so perhaps he was the quiet one, busy running the store. It is also possible he was distracted by family obligations. Henry was married to Ontario-born Christina Maria Shore and the couple had six children.

On June 25, 1885, Mulholland Bros. ran an ad in the Manitoba Daily Free Press listing the many new items they had in stock, including blacksmith and livery stable supplies as well as articles for barbers, butchers, hunters and gardeners. They also carried bird cages and ivory-handled table knives.

Few of Winnipeg’s citizens were wealthy, the local economy was dependent on a good grain harvest, and shipping costs to Winnipeg were high. The business may have over-extended its inventory. In February 1889, a bankruptcy sale notice for Mulholland Bros. appeared in the paper, listing egg boilers and dog collars among the many items to be disposed of.4

Joseph returned to Montreal and, in 1890, he married Amelia Bagg (1852-1943). Amelia had inherited Montreal real estate from her father, Stanley Clark Bagg, and she was an independently wealthy woman. She was generous to family members in need, and in return, she was loved and respected by members of both the Bagg and Mulholland families. For Joseph, marriage to Amelia not only brought companionship, it also brought him a job in the Bagg family business as a real estate agent.

His good fortune did not last long, however. Joseph died of heart failure brought on by extreme heat in Montreal on July 15, 1897.5

As for Henry, after the Winnipeg store failed, he remained in Manitoba for a time — the family was still there in 1891 when the census was taken — but they eventually moved to Toronto, where Henry continued to work as a hardware merchant. After his death, his youngest son, Toronto lawyer Joseph Nelson Mulholland, commented that Henry had never regained his stride following the bankruptcy.6 When Henry died in Toronto in 1934, at age 84, his obituary did not mention the Winnipeg venture.7

This article is also posted on the collaborative family history blog https://genealogyensemble.com

Thanks to my distant Mulholland cousin for contacting me and telling me about his ancestor Henry. I had no idea that Joseph he and Joseph ran a hardware store in Winnipeg.

See also:

Janice Hamilton, “Henry Mulholland, Montreal Hardware Merchant”, Writing Up the Ancestors, March 17, 2016, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2016/03/henry-mulholland-montreal-hardware.html

Janice Hamilton, “The Life and Times of Great-Aunt Amelia”, Writing Up the Ancestors, June 21, 2023, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2023/06/the-life-and-times-of-great-aunt-amelia.html

Janice Hamilton, “The World of Mrs. Murray Smith”, Writing Up the Ancestors, Feb.24, 2016, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2016/02/the-small-world-of-mrs-murray-smith.html

Sources

- “The Late Mr. Mulholland”, The Montreal Star, Feb. 19, 1887, p. 8, Newspapers.com, https://www.newspapers.com/image/740882983/?match=1&terms=Henry%20Mulholland

- 2. Obituaries, The Vancouver Semi-Weekly World, July 16, 1897, Newspapers.com, https://www.newspapers.com/image/776743130/?match=1&terms=Joseph%20Mulholland%20Winnipeg

- 3. Letter from Henry Mulholland sr. to Henry Mulholland jr., Dec. 8, 1884, Mulholland family collection.

- 4. “Bankrupt Stock of Hardware Items of Mulholland Bros.”, Manitoba Daily Free Press, Feb. 21, 1889, p. 7, Newspapers.com, https://www.newspapers.com/image/778120441/?match=1&terms=Mulholland%20Bros.%20

- 5. “Late J. Mulholland. a man who was cordially liked by many friends in this city”, The Winnipeg Tribune, July 10, 1897, p. 5, Newspapers.com,

- 6. Letter from Nelson Mulholland to Fred Murray Smith, June 22, 1943, Mulholland family collection.

- 7. “Henry Mulholland Dies in Toronto”, Montreal Daily Star, Nov. 12, 1934, p. 17, Newspapers.com, https://www.newspapers.com/image/741983911/?match=1&terms=Henry%20Mulholland