One spring day in 1819, a young man named Benjamin Workman stood on the dock at Belfast, Ireland, trying to decide where he should immigrate to in North America. He had relatives in the United States, but before he booked his passage, he wanted to check on the safety of the vessels that were scheduled to leave soon.

He noted that the captain of the New Orleans-bound ship appeared to be drunk, the mate of the ship going to New York swore profusely, and the crew of vessel going to Philadelphia ignored his questions, but the captain of the Sally, bound for Quebec, impressed him favourably, so that’s the ship he chose. He later noted that this had been a lucky choice since yellow fever was widespread in American port cities that year.1

Benjamin left Ireland on April 27 and arrived in Montreal a few weeks later. He was 25 years old and had 25 guineas (a coin worth one pound, one shilling) in his pocket.

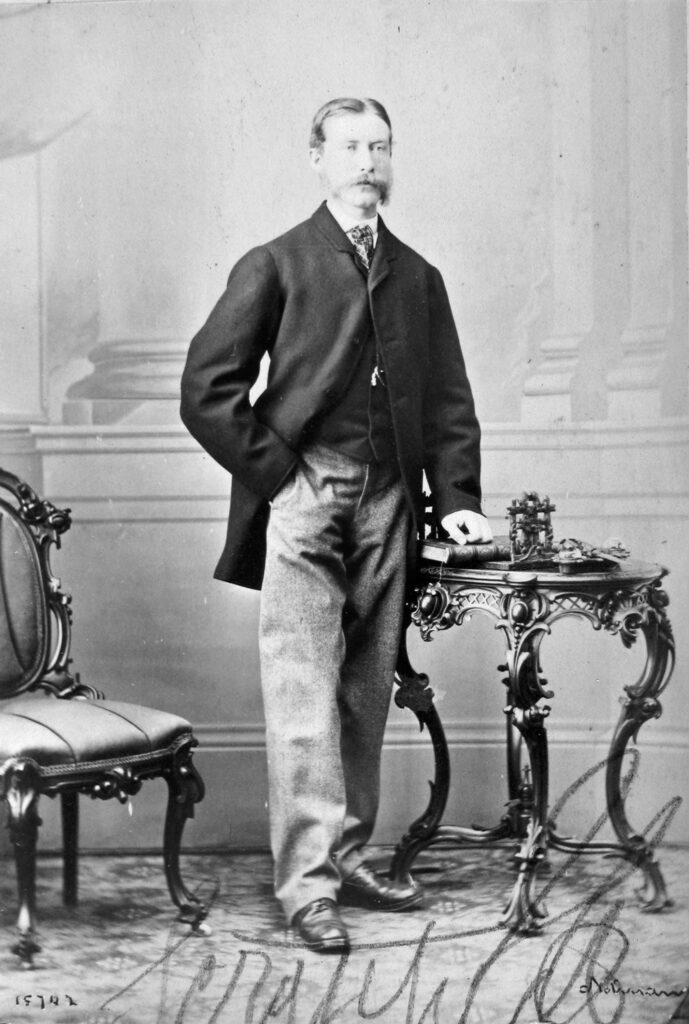

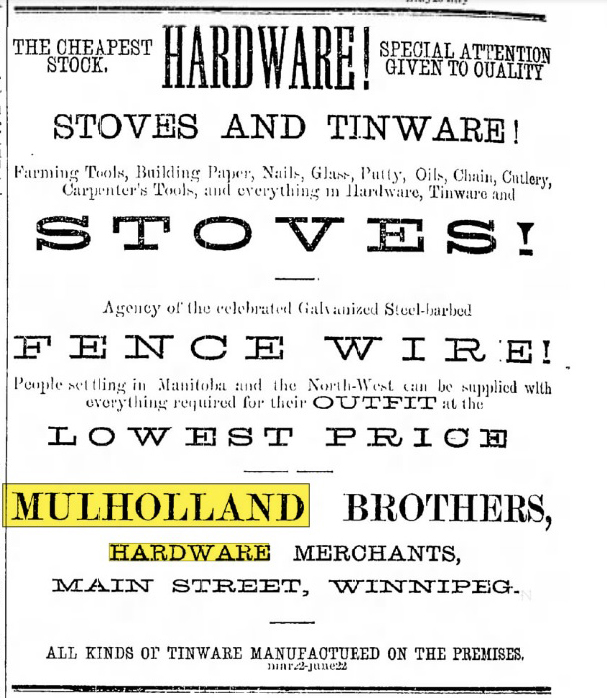

His choice of Canada turned out to be a good decision: within 10 years, all of his eight younger siblings and both of their parents had followed him. The Workmans were all hard-working, ambitious and smart, and they took advantage of the opportunities available to them in their new homeland. Four of Ben’s brothers (Alexander, Joseph, William and Thomas) became prominent in business, medicine and politics. His only sister, Ann (1809-1882), married Irish-born Montreal hardware merchant Henry Mulholland and was my great-great-grandmother.

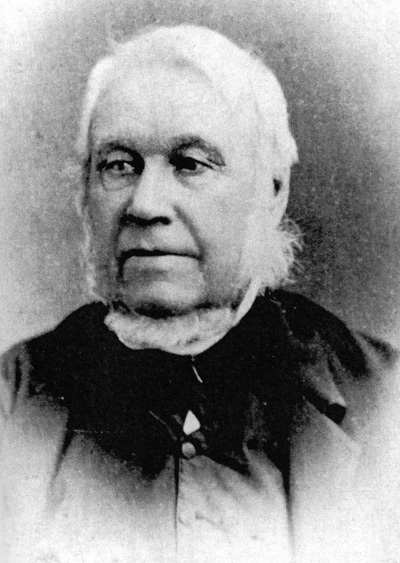

Benjamin’s parents were Joseph Workman (1759-1848) and Catherine Gowdey (1769-1872). Ben was born on Nov. 4, 17942 in the village of Ballymacash, County Antrim, near Lisburn, where the family lived in a small house near the top of a hill.

Joesph was a teacher in Ballymacash, but he left teaching for a job as a manager for a local landowner, and as a deputy clerk of the peace for the area. Without its only teacher, the local school had to close, so young Ben started studying on his own, reading the Bible and geography books while his father helped him with arithmetic. When Ben was 11, Joseph apprenticed him to a linen weaver, but it soon became clear that Ben had no talent in that field. What he really wanted to do was study. Eventually, Ben went back to school, where he excelled in grammar and the classics. After he graduated, he found a teaching job in Belfast, then another position near Lisburn.

Ben’s decision to leave Ireland was influenced by an event that took place in 1817. As he was eating his evening meal at his parents’ home, a dozen beggars came in the gate and asked for food and money. Perhaps realizing how widespread poverty was in Ireland, he began to think about going to North America.3

Montreal suited Ben well: other Irish and Scottish immigrants arrived there around the same time, and there were work opportunities for all. He immediately found a teaching job, but after that school’s owner disappeared with its funds, several parents who had noticed what a good teacher Ben was started a new school, with Ben as headmaster.

The Union School, as it was called, was unique. For one thing, girls were admitted, although they were taught separately by a female teacher. It was also successful. By the spring of 1820, it had 120 pupils, and it remained the largest English school in Canada for 20 years.4 Several of its graduates went on to have distinguished careers in business and politics. In 1824, Ben became the sole owner of the school, but he eventually turned over the responsibility of running it to his brother Alexander, who had come to Montreal in 1820.

In 1829, Benjamin switched careers and became a newspaper editor, partnering with a friend to purchase a weekly Montreal newspaper, the Canadian Courant. It had been founded in 1807 as the Canadian Courant and Montreal Advertiser. Ben published the newspaper until 1834, using it to promote his liberal religious views, social welfare issues, and the temperance movement. When the paper ceased publication, Ben blamed distillers, saying that their advertising had dried up because of his support for temperance.

Meanwhile, Ben experienced several tragedies in his personal life, as he was married twice and became a widower twice. He married Margaret Manson, a teacher at the Union School, in 1823. The couple had no children and Margaret died seven years later. He married Mary Ann Mills on October 14, 1838, in Franklin, Michigan, and the couple had three children: Mary Matilda, born in July 1840; a son, Joseph, who was born in November 1841 and died at age 10 months; and Annie, born in July 1843. Mary Ann died two months after Annie’s birth, and Ben’s mother, Catherine, looked after his two daughters.

Soon after that, Ben took up his third career — as a druggist. For several years in the 1840s, Lovell’s city directory of Montreal listed “B. Workman & Co., chemists and druggists”, located at 172 St. Paul Street, corner Customs House Square.5 Meanwhile, he studied medicine at McGill University, graduating in 1853, at age 59. He was henceforth known as Benjamin Workman M.D., which helps differentiate him from several other Benjamins in the family.

During these years as a pharmacist and doctor, Ben demonstrated compassion and generosity, often providing care to people who were too poor to pay. Then, in 1856, he reinvented himself again and moved to Toronto, where he assisted his brother Joseph run the Provincial Lunatic Asylum, the largest and most progressive psychiatric hospital in Canada at the time.

Benjamin Workman is probably best remembered as the founder of the Unitarian Congregation in Montreal. In Ireland, the Workman family had attended the Non-Subscribing Presbyterian Church of Ireland in Dunmurry. Its members strongly believed in freedom of thought in religion.6

When Ben first arrived in Montreal, there were not enough Unitarians to organize a congregation, so he attended the St. Gabriel Street Presbyterian Church. When the city’s Unitarian congregation was permanently established in 1842, he played a key role.7

In 1855, Ben got into a disagreement with the congregation’s minister, Rev. John Cordner, a man he himself had recruited for the job. Benjamin argued that Cordner had excessive authority, and when the rest of the congregation sided with their minister, Ben withdrew from the church. Soon after, he moved to Toronto, joining the Unitarian congregation his brother Joseph had helped to found there. He got along well with the Toronto congregation’s members and their minister, and he ran the Sunday School there for many years.

Ben lived with his daughter Anne in Uxbridge Ontario at the end of his life, dying there on Sept. 26, 1878, several weeks short of his 84th birthday. He was buried a few days later next to the large Workman family plot at Montreal’s Mount Royal Cemetery.

This article is also posted on the collaborative family history blog https://genealogyensemble.com

See also:

Janice Hamilton, “Dr. Joseph Workman, Pioneer in the Treatment of Mental Illness” Writing Up the Ancestors, Oct 26, 2017, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2017/10/dr-joseph-workman-mental-health-pioneer.html

Janice Hamilton, “Henry Mulholland, Hardware Merchant” Writing Up the Ancestors, March 17, 2016, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2016/03/henry-mulholland-montreal-hardware.html

Notes:

The children of Joseph and Catherine Workman were: Benjamin (1794-1878), Alexander (1798-1891), John (1803-1829), Joseph (1805-1894), William (1807-1878). Ann (1809-1882), Samuel (1811-1869), Thomas (1813-1889), Matthew Francis (1815-1839).

Benjamin kept a journal in which he recorded his memories of growing up in Ballymacash, and an account of the Workman family’s 200-year history in Ireland. A large online database called A Family Orchard: Leaves from the Workman Tree, https://freepages.rootsweb.com/~database/misc/WORKMAN.htm, includes a family history going back to the 1600s, that was part of Ben’s journal. The late Calgary researcher Frederick Hunter prepared this site and database.

Catherine Gowdey’s name has been spelled in various ways, including Gowdie and Gowdy.

Thank you to Christine Johnston, former archivist and historian of the First Unitarian Congregation of Toronto for all the research she did on the Workman family.

Sources:

1. Christine I. M. Johnston, The Father of Canadian Psychiatry: Joseph Workman, Victoria: The Ogden Press, 2000, p. 16.

2. A Family Orchard: Leaves from the Workman Tree, https://freepages.rootsweb.com/~database/misc/WORKMAN.htm, accessed Jan. 31, 2025.

3. The Digger, One Family’s Journey from Ballymacash to Canada, Lisburn.com, http://lisburn.com/history/digger/Digger-2011/digger-19-08-2011.html, accessed Jan. 31, 2024.

4. Nicholas Flood Davin, The Irishman in Canada, London: S. Low, Marston, 1877, p. 334, Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/irishmanincanada00daviuoft/page/334/mode/2up, accessed Jan. 31, 2025.

5. Lovells Montreal Directory, 1849, p. 246, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (BAnQ), https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3652392, accessed Jan. 31, 2024.

6. Christine Johnston, The Father of Canadian Psychiatry: Joseph Workman, p. 15.

7. Christine Johnston. “The Irish Connection: Benjamin and Joseph and Their Brothers and Their Coats of Many Colours,” CUUHS Meeting, May 1982, Paper #4, p. 2.