Abner Bagg seems to have been the black sheep of the Bagg family, although I am not sure why. My great-aunt even insisted he was not related when, in truth, he was the brother of my three-times great-grandfather Stanley Bagg. Perhaps the problem was that Abner’s business had gone bankrupt.

Abner was born on August 5, 1790 in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. He was the son of farmer Phineas Bagg and Pamela Stanley. His mother died around 1793 and several years later the family left the United States, settling in La Prairie, near Montreal, Lower Canada.

By 1810, Abner was in business as a manufacturer and importer of hats. At his store in Montreal, he sold “ladies’ bonnets and gentlemen’s fine hats” as well as military hats. A few years later, he opened a hat-making factory in Terrebonne, northeast of Montreal, then a second store in Montreal and one in Quebec City.

On October 22, 1814, Abner married Mary Ann Wurtele, daughter of Quebec City shopkeeper Josias Wurtele, at the Anglican Cathedral in Quebec City. According to the marriage record, Abner was 25 and Mary Ann was 19. The couple eventually had six children, three of whom died as babies.

With his business doing very well, Abner purchased an empty lot in a suburb just west of Montreal. Between 1819 and 1821, he constructed a large stone house on the property, later adding a warehouse attached to the family home.

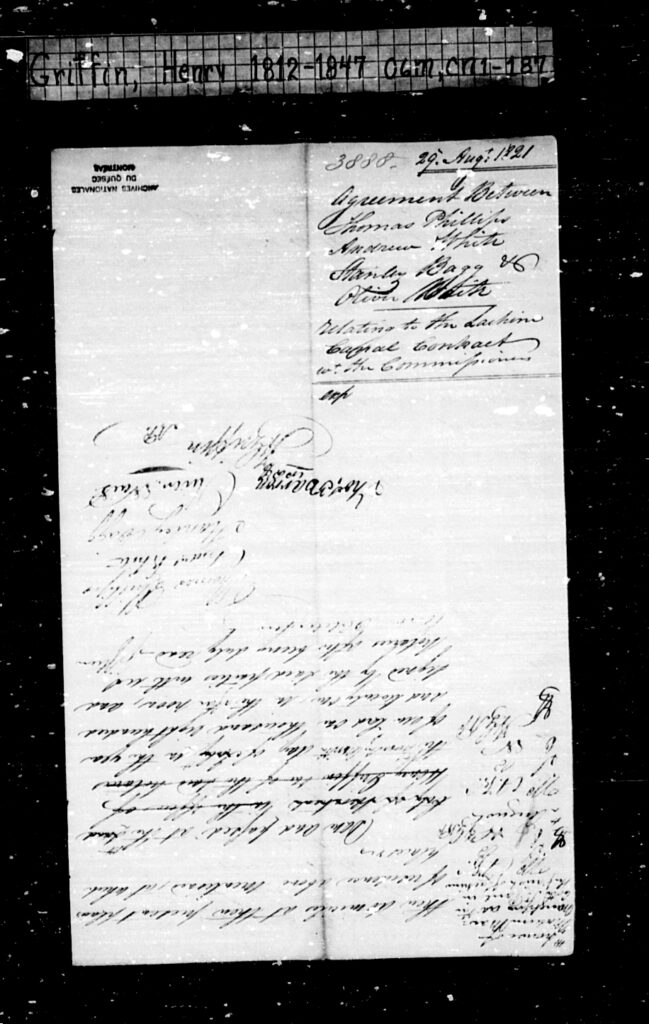

Meanwhile, Abner diversified his business interests. While running the shop, he was also buying white pine from the forests of the Chateauguay Valley, southwest of Montreal. He transported the logs to Montreal and to Quebec City. The big timbers were shipped to England and the smaller logs were cut into firewood. In the early 1820s, when his brother Stanley was one of the main contractors for the excavation of the Lachine Canal, Abner supplied goods such as gunpowder, food and timber to the canal builders. In the 1820s, he bought and sold shares in several steamboats that carried people and goods across the St. Lawrence River.

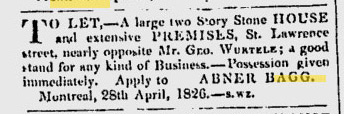

Abner always kept an eye out for real estate deals, especially at sheriff’s auctions. Sometimes he made improvements to the buildings and then sold them at a profit, sometimes he kept them as rental properties.

In the mid-1820s, however, things unraveled: his wife died in 1827, and his hat business went bankrupt. He had expanded too rapidly, using unsecured personal notes rather than cash, so when a large-scale commercial crisis reached Canada around 1825, sales fell and he was unable to repay huge debts to suppliers in England, or to others.

Bankruptcy was not unusual. There was never enough hard cash circulating in British North America, nor was there an extensive banking sector, so merchants had to rely on credit and promises to back up their friends’ and relatives’ loans. And after he went bankrupt, there were no rules to protect his creditors or to help him through the crisis. Abner’s personal credit was ruined.

After his business failed, Abner’s main source of income was rent from the houses he owned. He transferred these properties to his brother Stanley to hold in trust while the income went toward paying off his debts. Eventually, however, Abner had trouble feeding his family, and Stanley had to start selling the properties, including the family home.

On February 12, 1831, Abner remarried. His second wife’s name was also Mary Ann: Mary Ann Mittleberger. They married in Montreal’s Anglican Christ Church, and, although Mary Ann was Catholic and remained so all her life, their nine children were baptized Anglican.

Two months later, Abner and Stanley were both baptized at Christ Church. Along with a number of other New England-born Montrealers, Abner had previously been a member of the city’s Scotch Presbyterian Church. Perhaps the Anglican religion was now more in line with his beliefs, or perhaps he looked at the Anglican Church as a step up socially.

In his remaining years, Abner tried unsuccessfully to reopen the hat factory. He travelled a great deal, buying flour and salt pork as far west as Ohio, and selling it to military posts in Upper Canada.

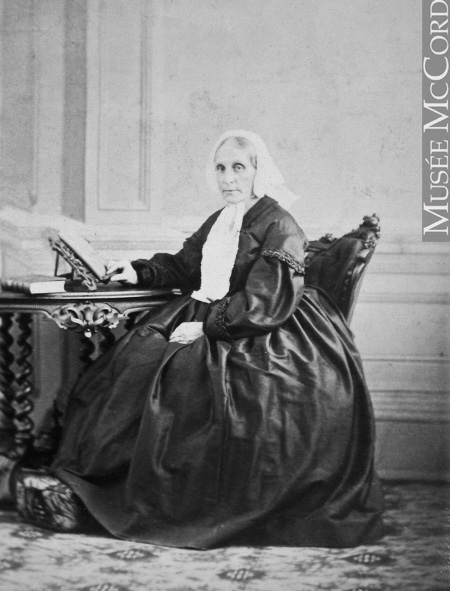

Abner died on March 21, 1852, age 64. The church record of his funeral referred to him as “gentleman,” so he must have restored some of his reputation in society. I have yet to find out where he was buried. He was survived by his widow, one daughter from his first marriage and four children from his second marriage. At the time of his death, the youngest was just four years old. The widowed Mary Ann lived until 1896.

Photo Credits:

eBay; Mrs. A. Bagg, Montreal, QC, 1862; I-4366.1 © McCord Museum; news.google.com

See also:

Janice Hamilton, “Stanley Bagg’s Difficulties” Writing Up the Ancestors, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2014/01/stanley-baggs-difficulties.html

Janice Hamilton, “An Economic Emigrant” Writing Up the Ancestors, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2013/10/an-economic-emigrant.html

Notes

Here is a list of Abner’s fifteen children, seven of whom lived to adulthood. I do not have all their marriage and death dates, only what I can find easily on Ancestry.com and in family records. Two of the daughters married two brothers, Henry and Samuel Shackell, who came from England.

Abner Bagg’s children with Mary Ann Wurtele:

- Sophia b. 1816, d. 1850; not married

- Abner Wurtele b.1818; d. 1818

- Mary Ann Louisa, b. 1819; m.

- John Porteous, 1856

- Caroline Eleanor b.1820; d. 1820

- Clarissa Matilda b. 1822; d. 1848; not married

- Catherine Pamela b. 1824; d. 1826

Abner Bagg’s children with Mary Ann Mittleberger:

- George Augustus Frederick Edward b. 1832; d. 1845

- Margaret Elizabeth Charlotte Eleanor b. 1833; d. 1834

- Emma b. 1835; d. 1835

- Alfred Solomon Phineas b. 1836; m. Priscilla Carden, 1876, Abbotsford, QC ; d. 1912 (he was sometimes referred to as A.S.P. Bagg, sometimes as Alfred S. Bagg)

- Charles Stanley Roy b. 1838; d. 1838

- Mary Eliza b. 1839; m. Samuel Shackell; d. 1915

- Emma Adelaide b. 1842; d. 1842

- Margaret Pamilla Roy b. 1844; m. Henry Shackell 1865

- Emily Caroline Stanley b. 1848; m. Charles William Radiger of Winnipeg, 1885

Abner’s exact date of birth is unclear. The record of his adult baptism in 1831 gives his date of birth as August 5, 1790, however, calculating his sister Sophia’s birthday from her age at death, she was born around February 20, 1791. At least one of those dates must be wrong. At his death in 1852, Abner’s age was recorded as 64, which would have meant he was born in 1788, the year brother Stanley was supposed to have been born. When he was married in 1814, Abner gave his age as 25, which would have meant he was born in 1789.

There was a portrait of Abner Bagg for sale on eBay a few years ago, so I made a screen shot of it. Unfortunately, the resolution is terrible. Also, I do not know whether this was the Abner Bagg of Montreal, since there were two other Abner Baggs in the United States at about same the time. They were all related, although I haven’t worked out the family tree.

There is lots of solid information on Abner’s business activities and financial difficulties. The pay records for his hat business, copies of letters and an 1816 inventory of his possessions are part of the Bagg Family Fonds at the McCord Museum in Montreal. In 1970, historian Donald Fyson used those records to prepare an article about Abner for the museum, and I used his paper as a source for this story. The Fonds also recently acquired material from the estate of Joan Shackell, a direct descendant of Abner.

Abner’s business agreements can be found among the notarial records at the Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec. For example, the act of notary N.B. Doucet 134-11205, 31 October 1823 is one of many wood contracts Abner signed. Jobin 215-4778, 30 March 1829 is a document in which Abner rented out a three-storey stone house he owned. Crawford 102-178, 9 July 1830 was an act in which Abner transferred the ownership of his properties to his brother and Stanley agreed to advance the funds to pay Abner’s debts.

Newspapers provide snapshots of people’s activities. This ad from The Montreal Herald, Oct. 14, 1826 is at https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=apgxAAAAIBAJ&sjid=likDAAAAIBAJ&pg=942,6061397&dq=bagg+montreal&hl=en. The Montreal Star archives came online on Newspapers.com in 2022.

Notices in the Canada Gazette referred to a variety of topics from property sales to official appointments. For example, a notice dated March 24, 1847 announced that Abner was a captain in the third battalion of the militia: http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/databases/canada-gazette/093/001060-119.01-e.php?image_id_nbr=138&document_id_nbr=1601&f=p&PHPSESSID=j1au0sblq8sejaol266jar2vp4

Digitized books can be an excellent source of information about the past. For example, I consulted Thomas Doige, An Alphabetical List of the Merchants, Traders, and Housekeepers residing in Montreal, to which is prefixed a descriptive sketch of the town. Montreal: printed by James Lane, 1819. https://archive.org/details/cihm_36464

Another book about the period is Robert Campbell, A History of the Scotch Presbyterian Church, St. Gabriel Street, Montreal. Montreal: W. Drysdale, 1887. https://archive.org/details/cihm_00397

The Centenary of the Bank of Montreal, 1817-1917, published by the bank in 1917, https://archive.org/stream/centenaryofbanko00bankuoft#page/78/mode/2up, shows that Abner was one of the bank’s original shareholders. Doige’s directory indicates that, two years later, he was one of the directors of the Bank of Canada. In 1826, the Bank of Montreal issued protests against Abner because he had not paid his debts (Griffin 187-6273 1 March 1826).

The Canada, British Army and Canadian Militia Muster Rolls and Pay Lists, 1795-1850 database on Ancestry.com shows that Abner Bagg was paymaster for the volunteer militia during the 1837-1838 rebellion in Lower Canada.