updated Sept. 21, 2024

My three-times great-grandfather Robert Mitcheson (1779-1859) appears to have been the kind of man who took a long time to settle down. He was lucky that he was born in the late 18th century. Previous generations hadn’t had as many career options.

His father and grandfather had both been farmers in County Durham, in northeast England, as were many of his relatives, but harvesting crops and raising animals didn’t appeal to Robert, so he became an iron manufacturer.1 Eventually, at around age 40, he settled in Philadelphia, got married and raised five children. Before he moved to the United States, there are only hints of his whereabouts and activities, but it is clear that he spent some time in the West Indies.

He was not the only one in his family to leave County Durham: his older sister, Mary, moved to Canada with her husband, John Clark, around 1797, and his brother William and his sister Jane moved to London.

Robert was the second child and oldest son of yeoman farmer Joseph Mitcheson (1746-1821), and Margaret Philipson (1756-1804). The word yeoman means Joseph was a landowner, although for many years he rented out the properties he owned and leased the farm where the family lived.

According to family lore, Robert was born at Eland Hall, near the village of Ponteland in Northumberland. Perhaps the family was renting Eland Hall Farm, which still exists and is located a few miles from Newcastle. Robert was baptized at Whickham Parish Church, in the town of Swalwell, where his mother had inherited property.

During Robert’s teen years, the family lived on a farm at Iveston, about nine miles northwest of Durham city. After his mother’s death in 1804, they moved into a house in Swalwell. Land tax records from 1810 show that Robert, now age 21, owned this property and that he was an iron manufacturer.

Iron ore, coal and limestone – the main ingredients of iron – were abundant in the region, and there were rivers for transportation and power. Iron had been produced in County Durham since the Iron Age, and Crowley Iron Works operated in the Swalwell area in the 1700s. Robert may have apprenticed as an ironmonger.

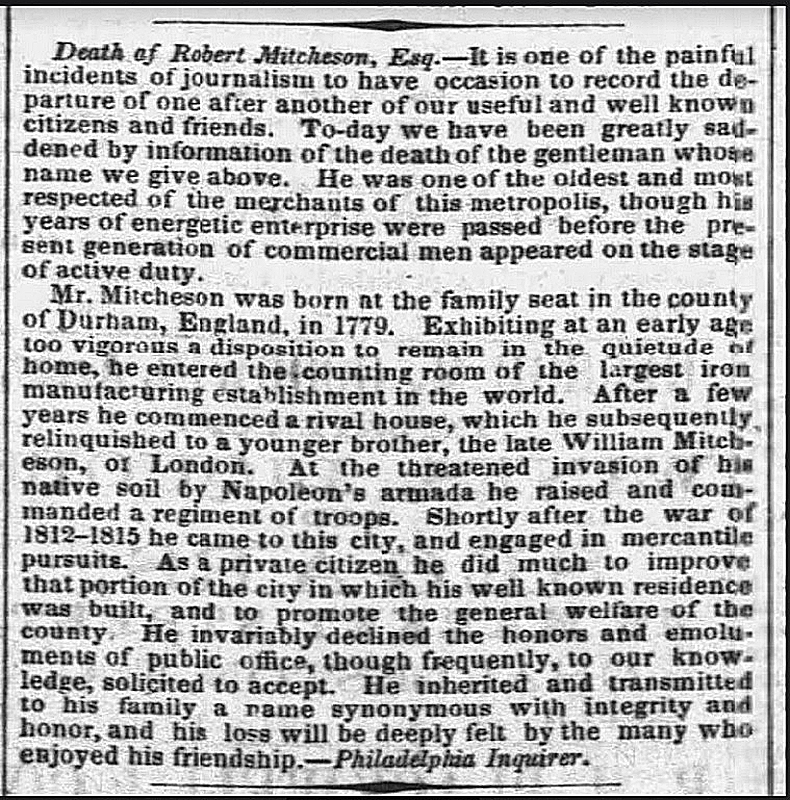

It is also possible that Robert was in the military in his youth. His March 28, 1859 obituary in the Montreal Herald and Daily Commercial Gazette, probably written by his daughter Catherine Mitcheson Bagg of Montreal, suggested that Robert was an officer in the British army during the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815). The article said, “he was a native of England and held, we believe, a commission as captain in the army.” That wording suggests that she wasn’t sure about this.

An obituary originally published in the Philadelphia Inquirer says that Robert raised a regiment to help protect England during the Napoleonic Wars, however, I have not confirmed this (perhaps because I don’t know much about researching the miliary). The obituary does, however, confirm that he worked for the world’s largest iron manufacturer (Crowley) although it suggests he had an office job, and it confirms his business relationship with his brother William Mitcheson, a London anchor-maker.

In December 1810, he was almost 30 years old and in business in London as an ironmonger. A search of the U.K. National Archives website shows that Robert Mitcheson and business partner Thomas Kempster, of Greenwich Street, Dowgate Hill, ironmongers, purchased insurance.2 Two years later Thomas and Robert dissolved their partnership.

Perhaps Robert remained in London for a while after that. His brother lived near the docks along the Thames River and some years later established an anchor-manufacturing business there.

According to another family story, Robert was “in the West Indies trade.” That phrase sometimes refers to the slave trade, but Britain abolished its transatlantic traffic in slaves in 1807, although slaves continued to work on the plantations of the Caribbean and in the southern U.S. for many years. It can also refer to exports to Caribbean countries, such as wheat and beef, or the importation of sugar from there. Perhaps Robert sold iron products, such as hoes and nails, to plantation owners in the West Indies. He definitely imported rum and sugar to the United States.

U.S. immigration documents show that Robert travelled from the West Indies to Philadelphia several times. He was listed as a passenger travelling from Antigua to Philadelphia aboard the Achilles in July 1816.3 He also sailed to Philadelphia on the Florida in March 1817, and the vessel’s cargo manifest showed that he had a shipment of sugar and rum, picked up in Kingston, Jamaica, on board with him.

In October 1817, Robert travelled from Antigua to the Philadelphia, with the intention of settling there. Within a year he was married and a new father, and he began a new career, this time as a distiller.

I will explore Robert’s life in America in my next post.

Notes and Sources

- A legal document identified Robert Mitcheson, late of Swalwell, now of Philadelphia, as an ironmonger: Clayton and Gibson, Ref No. D/CG 7/379, 16 September 1835, Durham County Record Office.

- 2. Sun Fire Office, MS11936/452/, 3 Dec. 1810, London Metropolitan Archives, www.nationalarchives.gov.uk, entry for Robert Mitcheson, accessed Jan. 21, 2023.

- 3. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. Passenger and Immigration lists, 1800-1850, www.Ancestry.ca, entry for Robert Mitcheson, accessed Jan. 22, 2023.

Thank you to the Riverside N.J. Historical Society for finding the Philadelphia Inquirer obit.