Part 1: Ireland

Genealogists suggest that when you are having trouble going backwards, go sideways instead. After two weeks of sideways research, I have turned up a lot of great-great-uncles, aunts and distant cousins, but I have no idea whether all this hard work will help me find my elusive three-times great-grandparents. Part of the problem is that the earlier ancestors were in Ireland, the ones I have been discovering had immigrated to Brooklyn, New York, and I live in Montreal.

My great-great grandmother, Martha Bagnall Shearman, was born in Waterford, Ireland, according to the 1861 Canadian census. She married Englishman Charles Francis Smithers at the Church of Ireland Cathedral of Holy Trinity, Waterford, Ireland, on September 10, 1844. Her parents’ names were not identified on the marriage record. One of the witnesses at the wedding was Thomas Shearman, who was probably Martha’s brother, cousin or uncle.

Three years later, the couple immigrated to Canada where Charles became a banker, and they started a family that eventually grew to include 11 children. For several years, Charles was the Bank of Montreal’s senior agent in New York City, and the Smithers family lived in Brooklyn. They eventually returned to Montreal and, in 1881, he was named president of the Bank of Montreal, a position he held until his sudden death in 1887. The widowed Martha may have then moved back to Brooklyn, where she had relatives, and she died there in 1897, age 71. Charles F. and Martha B. Smithers are buried in Brooklyn’s historic Green-Wood Cemetery.

Martha Bagnall Shearman is special to me because she is the earliest ancestor so far in my maternal line: I have inherited her mtDNA. I’d like know who her parents were, especially her mother. It is very likely that Bagnall (or Bagnell) was a family name, perhaps her mother’s. St. Clair may also be a family name, since two members of later generations, one in Montreal and one in Brooklyn, had St. Clair as a middle name.

Two Shearmans are listed in the city of Waterford in the Slater’s Commercial Directory of Ireland, 1846: Alexander and William. Both were attorneys, perhaps one of them was Martha’s father. On the same directory page, listed under bacon merchants, was Charles F. Smithers. However, it is also possible the Shearman family came from neighbouring county Kilkenny. Time, and a lot more research, will hopefully tell.

Part 2: Brooklyn

When my great-grandmother Clara Smithers was growing up in Brooklyn, New York, she had an autograph book filled with poems, drawings and signatures from friends and relatives. Among those signatures was that of May P. Shearman. I knew that Clara’s mother, whose maiden name was Martha B. Shearman, had a brother in Brooklyn, so I wondered whether May was her cousin. Indeed, May P. Shearman, aged four, was in the 1860 U.S. Federal Census along with her father, Henry, a lumber merchant, his wife Elizabeth, and Harriet, her younger sister. Eventually, Henry and Elizabeth had 10 children. Henry, born in Ireland around 1832, died in 1882.

Recently, I came across an article in the Brooklyn Eagle, dated Dec. 4, 1895, describing the wedding of Helen St. Clair Shearman, daughter of the late Henry Shearman, at Marcy Avenue Baptist Church. The article noted that Helen was the niece of Charles F. Smithers, president of the bank of Montreal, confirming the family connection.

One of the ushers at Helen’s wedding was her cousin William B. Shearman. The 1892 New York State census indicated that William B. was the son of Thomas Shearman and his wife Deborah, and that William had at least two siblings. So, it seemed, Martha had two brothers, Henry and Thomas, in Brooklyn. Like Henry, Thomas was in the lumber business. He was born in Ireland around 1822, and he died in Brooklyn in 1894.

There was a well-known lawyer in Brooklyn at the time, Thomas G. Shearman, and I had to be sure that the records I collected belonged to my Thomas and not to the other one. Spelling was another challenge: the census spelled my Thomas as Sherman, not Shearman. And to add to the confusion, the Shearman children all seemed to have had nicknames like Bessie, Harry, Hattie and Nannie. In fact, May P. Shearman’s name was actually Mary.

For a day or so, I was very pleased with myself, satisfied that I had made a good start at finding Martha’s siblings. But one thing was still bothering me: the 1880 census listed John Boate, bookkeeper, living with Henry Shearman’s family. He was identified as Henry’s brother-in-law. John’s sister and his three children were also listed. Who were these people? I searched for John Boate and Shearman, leaving the wife’s first name blank. Sure enough, Maria Ann Shearman turned up, a probable sister for Martha, Henry and Thomas. She died in 1879 from an abdominal tumor, which helps explain why her husband and children were staying with relatives a year later.

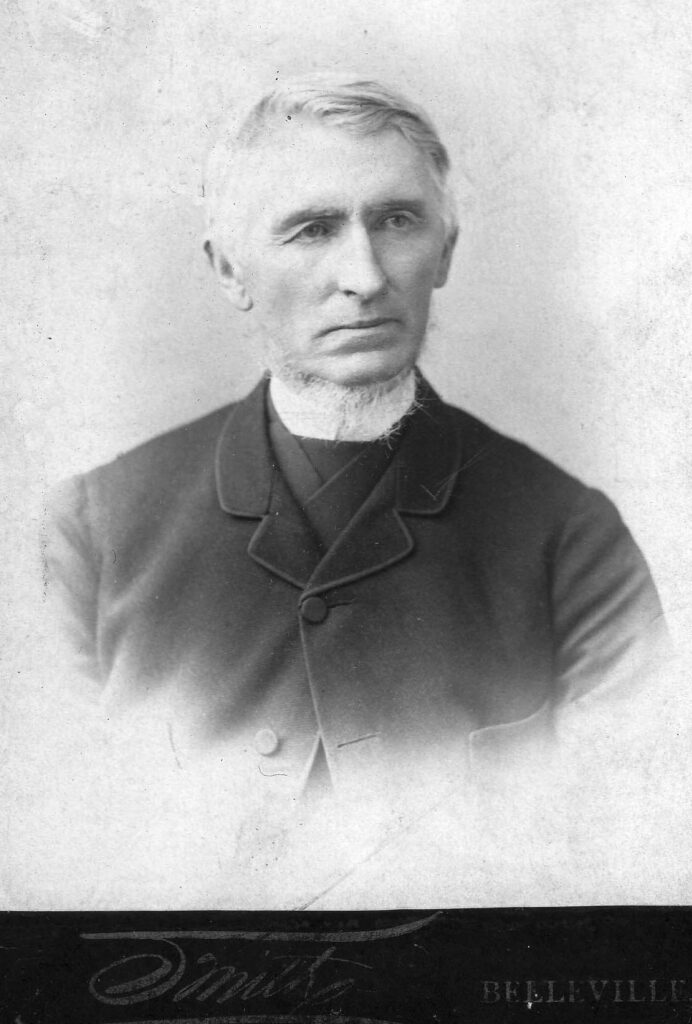

I do not yet have a clue where any of the Shearmans are buried, nor have I found some of the birth, marriage and death records that should be there. That is no doubt due to my inexperience researching in New York State, and the fact that many records are not online. I also wonder whether some of those 19th century photographs I inherited, unidentified except for the names of the Brooklyn photographers who took them, were Shearmans. I am especially curious about May P. Shearman, who helped point the way to her family. The last record I found for her is in the 1915 New York State census, age 59, no occupation, living as a roomer with her widowed sister Elizabeth King, 35, school teacher.

I still wonder whether Martha, Henry, Thomas and Maria Ann had any other siblings, and whether finding any of these Americans will help identify their parents in Ireland. And it would be a bonus to find some living descendants.

Updated with photo March 23, 2015

Updated Sept. 10, 2016: In answer to my final question, the Shearmans had another sibling in New Zealand, and there are records of the Shearman family in Ireland going back to the late 1600s. See “Breaking Through My Shearman Brick Wall,” posted July 6, 2016, https://genealogyensemble.com/2016/07/06/breaking-through-my-shearman-brick-wall/