Many of the family stories I heard about my ancestors turned out to be incomplete or wrong. One story that proved to be true is the claim that my three-times great-grandfather Stanley Bagg (1788-1853) was a contractor who built Montreal’s Lachine Canal in the 1820s. The family story did not explain how he got the contract, what his role was, or what a complex undertaking it was.

In the days before highways and railways, the St Lawrence River was an important transportation corridor between the Atlantic Ocean and the heart of North America, but the Lachine Rapids, a few kilometers upstream from Montreal, made navigation difficult. People talked about the need for a navigable canal around the rapids, but the government did not want to spend the money.

During the War of 1812, the St. Lawrence River was used to transport military supplies from Montreal to Kingston, and the government began to recognize its importance. But just as the population of the Great Lakes region began to swell with new immigrants, the commercial potential of Montreal and the St. Lawrence River became threatened when the Americans began construction of the Erie Canal between Lake Erie and the Hudson River in 1817.

Two years later a group of Montreal merchants received permission to build a canal with private financing. They hired British engineer Thomas Burnett to propose a route, but when they read his report, they realized the project was too big to be built by private enterprise. Finally the Legislative Assembly of Lower Canada agreed to pay for the canal. It set aside 45,000 pounds and appointed a Board of Commissioners to manage the project. One of the commissioners was Thomas Phillips, a master plasterer.

By now it was the end of June 1821 and, if any excavation work was to be done that year, it had to start soon, before the rain and cold of autumn arrived. Suddenly, the tender process was underway and moving quickly. No one had ever undertaken a canal excavation and construction project of this magnitude in Canada before, so the bidding process must have involved a lot of guesswork. “The lowest bid was submitted by a group composed of Stanley Bagg, Oliver Wait, Andrew White and Thomas Phillips (who had resigned his appointment as commissioner)”, historian Gerald Tulchinsky explained in his 1960 thesis about the canal’s construction. “They were awarded the contract, not only on the grounds of price, but because they offered to dig the whole canal, whereas others offered to excavate only sections,”

The four partners all had some construction experience and Phillips, as a former member of the commission, must have had a good idea of the canal’s requirements. White was a carpenter, and Bagg and Wait had previously collaborated on several construction contracts for the British army.

The commission’s 1821 annual report described the four men as “persons of character and considerable property.” On this project, Bagg acted as treasurer. The commissioners responded to the Phillips groups’ offer, forcing them to take risks on the types of soil and the amount of rock they might encounter as they excavated. Then, on July 9, the commission awarded them the contract.

The ground-breaking ceremony took place on July 17 with the commissioners and the four contractors in attendance, along with the labourers who had already been hired. Newspaper reporters, friends and family members and Lachine residents looked on. Commission chairman John Richardson turned the first sod and each of the commissioners and contractors took a turn with the ceremonial shovel. Richardson made a short speech, a military band played and everyone dug in to the meat pies and beer provided. Soon the commissioners and contractors withdrew to a nearby inn for more toasts, while some of the drunken labourers back at the construction site got into fights.

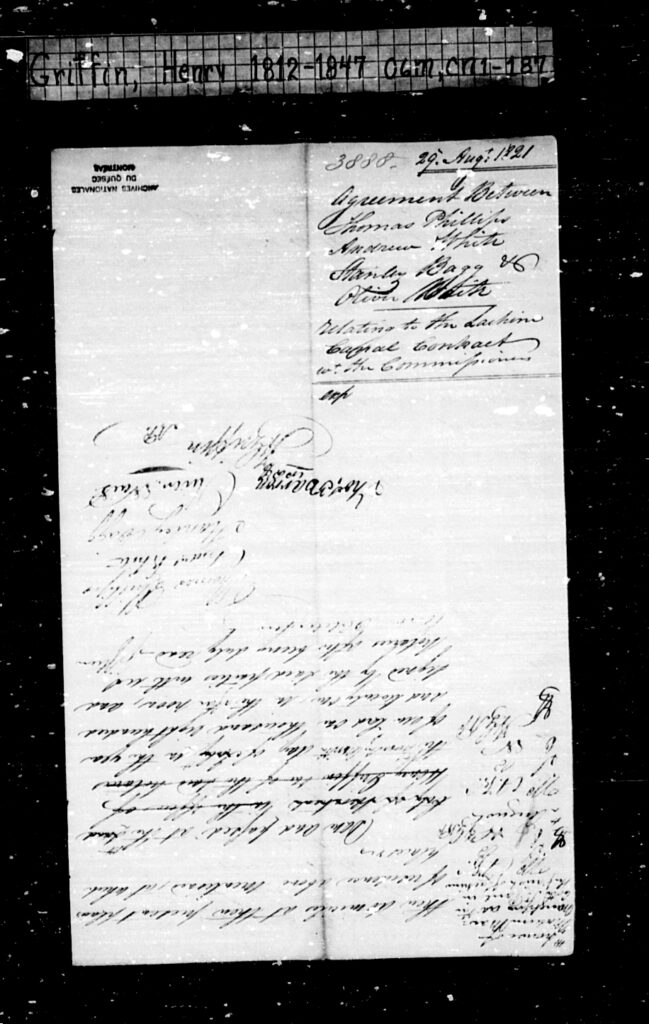

As the contractors began to get organized and hire subcontractors, they still had to finalize their own partnership. On August 29, Phillips, White, Bagg and Wait signed an agreement with each other, pledging not to undertake any other contracts until this one was complete.

The job took four years, thousands of labourers were involved, costs ballooned and the contractors encountered many unexpected difficulties. My next post will describe in more detail the massive construction project Stanley Bagg and his colleagues undertook.

Notes

The historical background for this article comes from Gerald Tulchinsky’s 1960 M.A. thesis for the McGill University Department of History, “The Construction of the First Lachine Canal, 1815-1826”. It can be found at the McGill library and online, http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/obj/thesescanada/vol2/QMM/TC-QMM-112940.pdf. University theses are an often overlooked resource; they can provide background on a variety of subjects, and the bibliographies they include can identify other sources. To search a list of Canadian theses, see http://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/services/theses/Pages/theses-canada.aspx.

I also consulted primary sources to learn more about my ancestor’s role in this project. One of the best sources of information about the construction of the canal is the Bagg Family Fonds at the McCord Museum in Montreal. Members of Stanley Bagg’s family kept his records and eventually donated them to the museum’s archives. The Lachine Canal collection (P070/A3.1 to P070/A3.5) includes contracts and account books, and many names are mentioned.

The minutes and annual reports of the Lachine Canal Commission, 1821-1842, are held in the archives of Library and Archives Canada in Ottawa, RG43-C-III-2 and R555-5-2-E. They are on microfilm, but I managed to see the original documents. It appears they are now in the process of being digitized.

The third primary source of information for this topic are the records of the Montreal notaries who wrote the contracts. Henry Griffin handled the agreement between the four contractors; see his act number 187-3888, dated 29 August, 1821. Griffin’s records are available on microfilm at the Bibliothèque et Archives nationale du Québec in Montreal and should eventually be digitized.