I’m in vacation mode right now, taking a break from writing my blog and spending some time at Biddeford Pool, the Maine seaside community where my mother and her parents spent their summer holidays. This is an article my mother wrote in the 1980s in which she described her memories of those family vacations. It sounds pretty unsophisticated, but it also sounds like they had a lot of fun. By the way, she mentioned attending services at St. Martin’s in the Field Episcopal Church. This past weekend, that church celebrated its 100thanniversary. JH

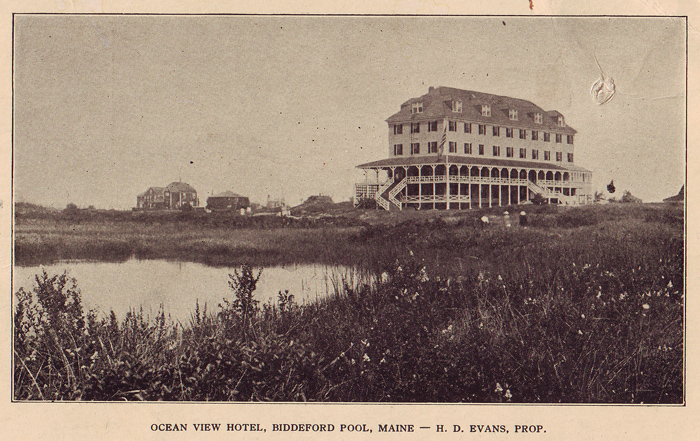

Summer at the Ocean View Hotel

by Joan Hamilton (1918-1994)

In the twenties and thirties, my family spent summers at a hotel overlooking the beach in Biddeford Pool, Maine. The Ocean View was a family-type hotel catering to a great extent to Canadians, especially Montrealers, since it was only 300 miles from Montreal. In the early days, we used to take the overnight train to the city of Biddeford. Frank, the man of all work at the Ocean View, met us at the station and drove us to the coast. It was a banner day in the 1930s when the first person did the drive by car from Montreal in one day.

The Ocean View letterhead read, “Henry D. Evans, Prop.”, and a proper proprietor he was. Fully in charge of all that went on in the hotel, and knowing all of us children well enough to tell us off if we got out of hand, he nevertheless had a wonderfully dry sense of humor. I’ll always remember the time he answered the one and only public telephone in the front hall. The call was for a very popular teenage friend of mine who was being pursued by a number of boys, amongst them one named Black and another whose surname was White. Mr. Evans came to the dining room door and boomed out for all to hear, “Margot, it’s for you. I don’t know if it’s a Black or a White.”

The kitchen was supervised by Mrs. Evans, who managed to produce delicious meals in an antiquated kitchen with coal stoves and ice boxes. The ice came from an old shed down the road where it was stored under layers of sawdust. The fare was simple by today’s standards, but always fresh and perfectly cooked, and with choice enough to suit everyone’s tastes. How my mouth waters when I think of that Saturday night special, “Boston baked beans, brown bread.”

The Ocean View was far from luxurious. There were no elevators, few private bathrooms, no telephones in the rooms and wide, dark linoleum hallways that echoed to our footsteps. We quickly learned to recognize everyone’s individual pattern as they walked down the hall. If we were up to some mischief, it gave us lots of time to hide the evidence.

There were a lot of children at the hotel and many of us had nannies, so we ate in the children’s dining room. It was in a glassed-in area off one of the balconies, with a marvelous view of the dunes and the sea. Putting us in our own dining room was also an effective way of keeping us out of the hair of the adults at a time when children were supposed to be seen but not heard.

The balconies of the Ocean View, with their wood and cane rocking chairs, were ideal for children’s games. On rainy days when we could not get out of doors to play, we would pull the chairs into a long line for a game of trains, turn them upside down for hiding places or houses.

Sometimes travelling shows came for the evening. Usually they were magicians who made shredded newspapers whole again and pulled rabbits out of hats. The chairs in the lobby were pulled into rows and parents and children alike watched the entertainment. Afterwards, the hat was passed. This must have provided a pretty meager living for the entertainers.

Sunday evenings were hymn-singing time, with one of the guests playing the piano and a group of us children gathered around singing. “Now the Day is Over” and “For Those in Peril on the Sea” always seemed to me dramatically mournful and appropriate, while the fundamentalist fervour of songs like “Shall We Gather at the River” and “Onward Christian Soldiers” had us raising the roof with our voices. After this observance of Sunday as a special day, everyone played games again. That is, everyone but me. My strict Presbyterian upbringing meant no Sunday games allowed.

Sundays also included a morning walk across the golf course to St. Martin’s in the Field Episcopal Church. Straw hats and white gloves were de rigueur for the women and girls, while the men looked handsome in navy blue blazers and white flannel pants.