This story is slightly complicated because of the similar names: generation one was Robert Stobo and his wife Elizabeth Hamilton; generation two was Elizabeth Stobo and her husband Robert Hamilton.

The story of my two-times great-grandgrandparents’ move from Scotland to Canada is legendary in my branch of the Hamilton family. Robert Hamilton (1789-1875), a weaver from Lesmahagow, Lanarkshire, moved to Glasgow with his wife, Elizabeth Stobo (1790-1853), and children to earn money for the move to North America. They boarded a ship bound for New York in the spring of 1830, and reinvented themselves as farmers in Scarborough Township, Upper Canada.

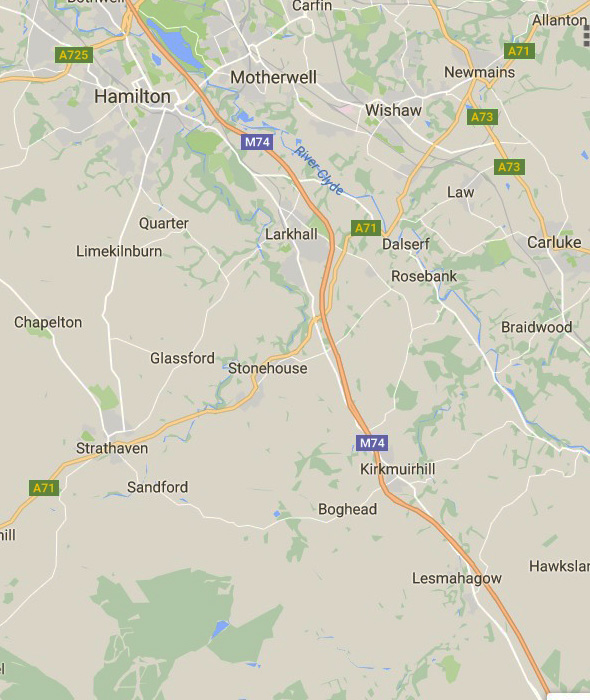

In 2012, my husband and I visited Lesmahagow, about 20 miles south of Glasgow. We looked for my Hamilton ancestor’s grave in Lesmahagow parish cemetery, gazed at the sheep grazing on the rolling hillsides and breathed in the cool Scottish air. From Lesmahagow, we drove to Avondale Parish Church in nearby Strathaven, where Elizabeth Stobo was baptized in 1790, “lawful daughter of Robert in Braehead.” We also visited Stonehouse parish, where Elizabeth and Robert were married in 1816.

All I knew about Elizabeth’s background was her place of birth and her parents’ names, Robert Stobo and Elizabeth Hamilton. Recently, I delved into the Stobo family tree and came up with a few surprises, notably that Elizabeth’s father led the way to Canada when he was 60 years old, and that several of her siblings also immigrated.

Robert Stobo was probably born in Avondale parish on July 16, 1764, the son of James Stobo in Braehead. When he married Elizabeth Hamilton in 1789, the marriage proclamations were read at both Avondale Parish Church and at Dalserf Parish Church, the bride’s parish.

Robert and Elizabeth moved several times during their child-rearing years, although they did not leave a relatively small area in southern Lanarkshire. Their children’s baptismal records show they lived in Braehead in Avondale parish, Dalserf parish, and Auchren in Lesmahagow parish. According to a reference letter from their minister that they brought with them to Canada, they also lived in Stonehouse parish for about nine years before leaving Scotland.

The minister who baptized Robert’s daughter Janet in 1792 usually noted each father’s occupation in the parish register. On the page where Janet was listed were a labourer, a shoemaker, a servant and a weaver. Unfortunately, the minister did not mention Janet’s father’s occupation. Robert may have been a tenant farmer, or he may have worked in the lime kilns around Braehead. Lime was quarried in the region and burned in kilns before it could be used to improve soil for agriculture, or in mortar for building.

Meanwhile, the early years of the 19th century were difficult ones. The Scottish economy was experiencing a recession, the weather was poor and, if Robert was a farm labourer, wages were low. Many families in lowlands Scotland, especially in Lanarkshire and Renfrewshire, were dependent on charity for survival. The government began offering assistance with travel costs to people who wanted to relocate to Canada. Perhaps Robert decided to take them up on the offer. The Stobo family left Lanarkshire in the spring of 1824.

The Stobos were one of the first families from Lanarkshire to arrive in Scarborough Township, settling on a piece of land near the Scarborough Bluffs overlooking Lake Ontario. Daughter Elizabeth and her family followed them to Scarborough six years later.

Robert Stobo was 60 when he started his new life in Canada, and his wife was 61. Several of their children were already adults, so some family members remained in Scotland while others left. According to “The Stobo Family: Scarborough, 1824 –“ (see note below) their children were:

Elizabeth, b. 25 June 1790; m. Robt Hamilton 15 April 1816, Stonehouse; d. 15 April, 1853, Scarborough. They had six children, the youngest of whom, James Hamilton, was my great-grandfather.

Janet b. 3 March, 1792, m. Coppy, d. 30 April 1816. Her birth in Braehead, Avondale parish, is included on Scotland’s People, but I have not confirmed her marriage or her death.

Barbara, christened 14 March 1794, Dalserf parish; m. Borwick. The marriage information comes from The Stobo Family manuscript. Two genealogy entries on Familysearch.org say Barbara married Thomas Borwick, 22 October 1832, Scarborough Township.

James, b. 7 Feb. 1896, m. Jean Muir, Scotland. His date of birth is confirmed in Lesmahagow parish on Scotland’s People. Ancestry.ca lists James Stobo m. Jean Muir, June 1827, Culter, Lanark.

Robert, b. 3 Feb 1798, according to The Stobo Family manuscript, however, I have not found a church record of his baptism. According to The Stobo Family manuscript and a letter from William McCowan in Lesmahagow to his nephew Robert McCowan in Scarborough, dated 9 March, 1836, Robert Stobo jr. was probably lost at sea.

Helen, b. 6 February 1800, m. 1. James Stobo of Bog, m. 2. Neil McNeil. Her baptism in Lesmahagow is listed on Scotland’s People. Her marriage, 6 April 1823, to James Stobo, Stonehouse, and her marriage to Neil McNeil, 1 Sept. 1839, Stonehouse, are listed on Ancestry.ca. According to The Stobo Family, she had four sons, three whom remained in Scotland.

Margaret, b. 10 May 1805; m. Adam Carmichael. While her birth is recorded in the old parish records of Lesmahagow, I did not find a marriage record. The Stobo Family manuscript says she and Adam had several children. More research is needed.

Jean(Jane) b. 10 July 1807, Lesmahagow; m. 25 April 1834 Archibald Glendinning, Scarborough; d. 2 Sept, 1893, Scarborough. Archibald was a well-known farmer and merchant in Scarborough, and they had a large family.

John, b. 18 May 1811, Lesmahagow; m. 12 July 1836, Scarborough, Frances Chester; d. 16 May 1889, Scarborough. John was a farmer and had a large family.

See also:

Janice Hamilton, “From Lesmahagow to Scarborough,” https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2013/12/from-lesmahagow-to-scarborough.html, posted Dec. 13, 2013, revised Dec. 27, 2016

Janice Hamilton, “The Glendinnings of Westerkirk,” https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2016/12/the-glendinnings-of-westerkirk.html, posted Dec.3, 2016

Janice Hamilton, “The Missing Gravestone of Robert Hamilton and Janet Renwick,” https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2015/10/the-missing-gravestone-of-robert.html posted Oct. 28, 2015, revised Dec. 27, 2016

Notes and sources

“The Stobo Family: Scarborough, 1824 –“ is a typed family tree manuscript by Stobo descendant Margaret Oke. It can be found in the Ontario Genealogical Society collection housed at the Toronto Reference Library. Mrs. Oke said the references used were family recollections, family bibles and census records in the National Archives (now Library and Archives Canada.) This document was originally prepared by Miss Ethel Glendenning (1880-1976), who was a United Church missionary in India for many years. Miss Glendenning gave it to Miss Marjorie Paterson (1901-1980), and Mrs. Oke transcribed it in 1986. I have used this tree as a starting point, checking the names and dates it gives with other sources including the Scotland’s People website, Ancestry.ca, and Familysearch.org.

The Stobo Family says Robert senior’s date of birth was 16 July 1764. Scotland’s People lists two Robert Stobos born in Avondale in 1764: one is the above individual, son of James, and the other was born 5 October 1764, son of Robert, but both index listings lead to the same image: son of James, born in July. The Stobo Family manuscript has proved accurate in all the dates I was able to verify, so the July date is probably correct.

I have not been able to find any information on Robert’s wife Elizabeth. The name Hamilton was very common in Lanarkshire.

This article is also posted on the collaborative blog https://genealogyensemble.com