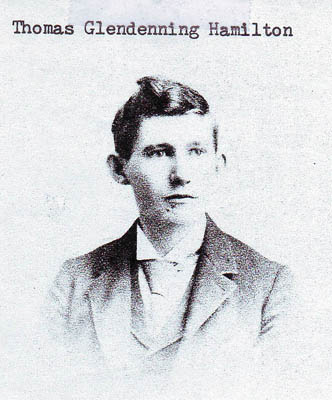

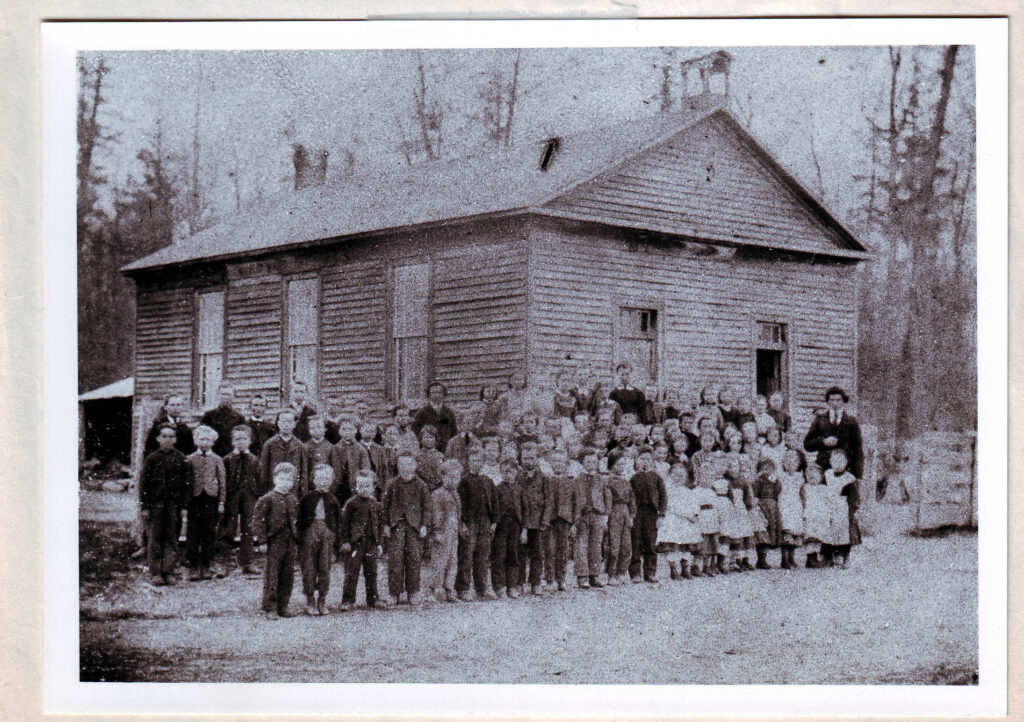

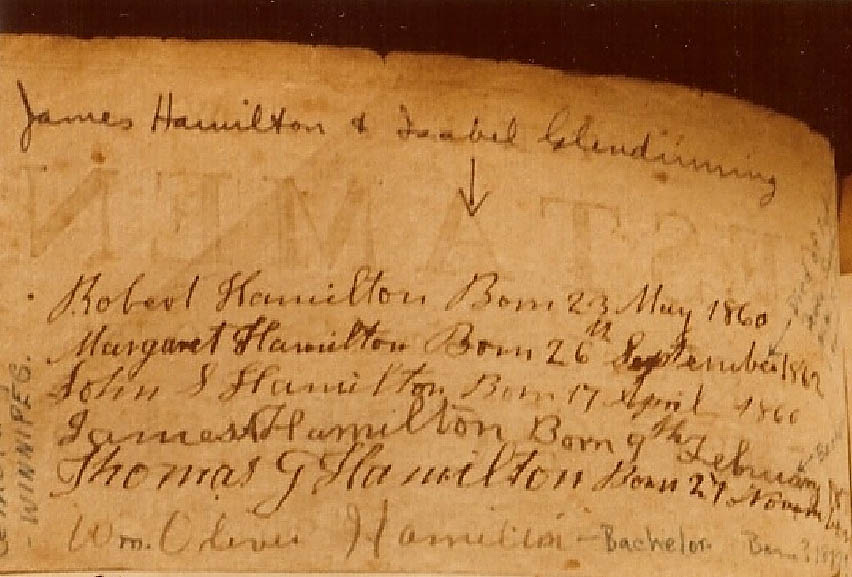

In 1885, 22-year-old Maggie Hamilton (1862-1886), was living on a farm in Saskatchewan with her parents and five brothers, including Robbie, her oldest brother. They had moved to Saskatoon three years earlier from Scarborough, Ontario. That winter, she wrote to her aunt, Mrs. James Gibson – her mother’s sister, Susan (Glendinning) Gibson — describing the sights they had seen and challenges they faced as prairie pioneers. Years later, someone typed a copy of that original letter and shared it with other family members. It is treasured.

Here is most of that letter:

Saskatoon, Feb. 21st, 1885

Dear Aunt,

How are you? We often wonder how you are getting along but never hear from you. I intended to have written to you soon again but although I did not, still was not because we had forgotten you. When we hear of anything being wrong with any of our friends in Ontario, it is then we feel we are far away.

We are living about 17 miles from the telegraph crossing so we might hear from you in a few hours. It seems a short time considering the distance we are apart. We were just about half way here when we got to St. Paul. We are about 110 or 120 miles south of Prince Albert and Battleford is about the same distance west of us. People out here do not seem to think much of traveling 18 or 20 miles. I believe people in Ontario would talk as much traveling 4 or 5 miles.

You would be surprised to see the long trains of freight carts there are on the trail sometimes. When we were coming in we met over one hundred which were said to be loaded with skins owned by Hudson’s Bay Company. The carts are mostly drawn by ponies, some by oxen. A train of 30 carts can be managed by five men. One man rides around on horseback to keep the train in order. One man was telling us last fall when he was on the trail, he met one hundred and fifty carts coming in which were loaded with flour. The two grist mills in Prince Albertwere burnt down last summer.

We had very dry weather here all last spring. Had no rain worth speaking of until the first of July so the grain had not time to ripen before the frost came. Old settlers say it was quite an unusual thing to have such drought as we had last summer.

We have far more snow here this winter than we had last. We have had good sleighing since the first of Nov. The lowest I have known the thermometer to be this winter was 55 degrees below zero. It is reported to have been 65 below in Moose Jaw this winter.

We expect the snow will be all gone in five or six weeks from now. Robbie was ploughing on the 3rd of April last spring. The ground was frozen so that he could not plough all day until about the middle of April.

Five men have gone down to Moose Jaw from Saskatoon this winter and have been out in some of the coldest weather. It would not be so bad if there were stopping places on the way. What would you think of sleeping out of the snow night after night for about two weeks as they have to do? The road or trail between here and Moose Jaw is good all summer ….

Robbie is just leaving for the Post Office so I must close now, hoping to hear from you soon.

Your affectionate niece

Maggie Hamilton