When Jessie Jean Forrester (1896-1961) married a Presbyterian minister, she committed herself to a very different life from the one she had been accustomed to growing up on the Manitoba prairie. For almost 25 years, the couple lived in India, where he served as a missionary.

There they were surrounded by the soaring Himalayas and elaborate temples, they suffered the heat of the central plains and humidity of monsoons, and they enjoyed eating Indian food. There were some scary moments too. On one occasion, they were staying in a camp, complete with tea service. Jessie got up to go to the bathroom during the night and, as she was passing through the privacy screen, she saw a tiger roaming the camp.

The youngest daughter of farmers Jack and Samantha (Rixon) Forrester, Jessie first left Manitoba as a teenager, accompanying her parents when they retired to Los Angeles around 1911.

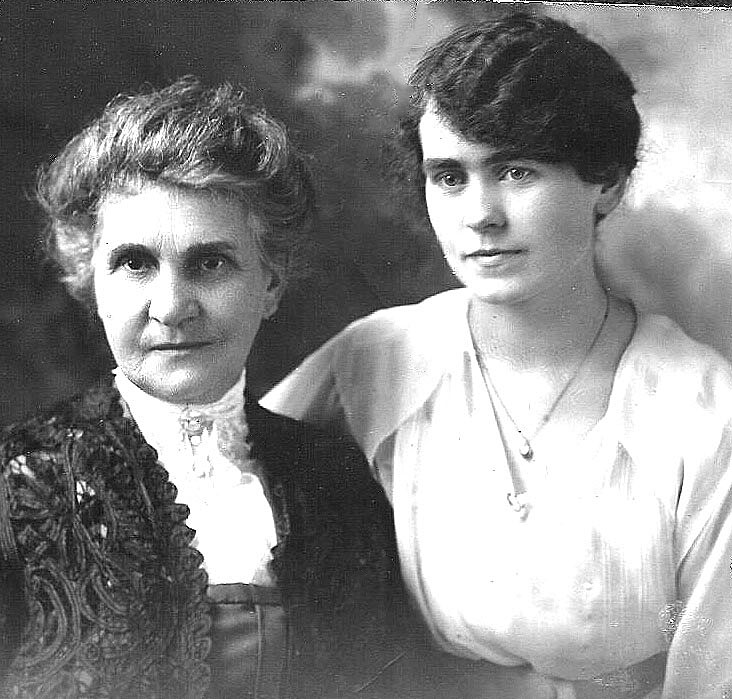

The 1920 U.S. census found her at age 24, living with her parents and working as a book keeper for a hardware store. The following year, she and her mother were counted in the 1921 census of Canada, staying with Jessie’s older sister (and my grandmother,) Lillian Hamilton, and her family in Winnipeg. They were probably busy preparing for the wedding.

Jessie’s husband-to-be, Thomas Benjamin McMillan, was born in 1888 in Margaret, Manitoba. The McMillan family eventually moved to Winnipeg. Tom graduated from Manitoba College with a degree in economics, then served as a lieutenant in the Royal Flying Corps during World War I. After the war, he returned to Winnipeg and completed a two-year course in theology.

Jessie and Tom were married on August 17, 1921. Three weeks later, the newlyweds left for India. Daughter Hazel Lillian (born 1922) and son Hugh Forrester (born 1924) were both born in India and attended Woodstock School, Landour, a school founded in the 19th century to educate the children of American missionaries. They also attended school in Winnipeg during extended visits to Canada.

Tom went to India as a Presbyterian minister, but after the creation of the United Church of Canada by Presbyterian, Methodist and Congregationalist congregations in 1925, he became a United Church missionary. Much of his work was based in the central Indian cities of Hat Piplia, Neemuch and Indore, in the state of Madhya Pradesh. When the weather in central India became too hot, the family retreated to the twin cities of Landour and Mussoorie, in the foothills of the Himalayas. When son Hugh McMillan and his wife visited Mussoorie in 1979, they found the cosmos flowers Jessie had planted many years before still seeding themselves and blooming.1

Besides serving as a pastor, Tom was also active on several committees. In central India, he served as chairman of the building committee for 10 years and secretary of the Evangelistic Commission for three years, and he was a delegate to the General Assembly of the United Church of North India and chairman of the Assembly Business Commission.

Tom and Jessie remained in India during World War II, but 19-year-old Hazel returned to North America in 1941 to stay her uncle and aunt in Los Angeles, and Hugh sailed to California in 1944.

Both were accustomed to long sea voyages, having travelled back and forth with their parents every few years to visit friends and relatives in Winnipeg and Los Angeles, but it must have been frightening for them to travel alone in wartime. Tom and Jessie came back to Canada for good after the war ended and before Indian independence.

The McMillans settled in British Columbia, where Tom ministered to several United Church congregations. After he retired in 1960 at age 72, they settled in Victoria, where he continued to visit the sick and served as an associate minister at Oak Bay United Church until 1964.

When Jessie died in 1961, aged 65, her obituary in the Ladysmith-Chemainus Chronicle called her “a woman of great dignity and artistic ability,” adding that the bazaars and festive occasions at the two local United churches where Tom had been minister for four years were made more attractive by her deft floral arrangements. Tom died in 1965 at age 77 and was buried beside his wife in Royal Oak Burial Park, Saanich, B.C..

Sources

- Walter Meyer zu Erpen, Mrs. Jessie Jean (Forrester) McMillan (29 March 1896-16 September 1961), sister of Mrs. T.G. Hamilton (1880-1956), and Reverend Thomas Benjamin McMillan (26 June 1888-25 July 1965), BA (University of Manitoba). Draft research report, 2015/12/26. Walter gathered his research from a number of sources, including telephone interviews with family members and United Church of Canada records.

This article is also published on the collaborative blog https://GenealogyEnsemble.com