A few years ago, someone gave me a copy of the Hamilton family tree, starting with immigrant couple Robert Hamilton ((1789-1875) and his wife Elizabeth Stobo (1790-1853) and including up to six generations of their descendants. Dates, places and occupations were not mentioned, however, and I wondered who these distant relatives were. Fortunately, the Hamilton family is well documented on Ancestry.ca, however, the Scottish habit of using the same names over and over makes the task confusing.

Their health also interested me. A number of my direct ancestors died of heart disease, so I wondered whether my great-grandfather James Hamilton’s siblings also suffered from this condition.

In 1829, Robert and Elizabeth immigrated from the town of Lesmahagow, Lanarkshire to Scarborough, Canada West, now a suburb of Toronto, Ontario, where many of their friends and relatives also settled. When they arrived, their children – Elizabeth, Janet, Agnes, Robert, Margaret and James — were still young. Robert continued to practice his trade as a weaver, meanwhile reinventing himself as a farmer.

Elizabeth Stobo died at age 63, while Robert Hamilton lived to the ripe old age of 86. Two of his sisters also came to Canada, and both had long lives. Agnes Hamilton (1791-1878) and her husband Robert Rae and their four young children arrived in Ontario in 1832. Robert Rae was killed by a falling tree within weeks of their arrival, but Agnes and her children eventually purchased their own farm in Lambton County, Southwestern Ontario. According to her death record, Agnes died of “old age” at 87.

Robert’s younger sister, Janet Hamilton (1800-1882), married in Canada. Her husband, farmer John Martin, was originally from Dumfriesshire. John died at age 83 and Janet succumbed to “dropsy from heart disease.” at 81. The Martins had two sons and a daughter.

Scarborough Township had fertile soil and the Hamiltons must have enjoyed their new lifestyle because the next generation were all farmers. The 1861 census – 32 years after the family immigrated – showed that four of Robert’s children remained in Scarborough Township and neighbouring Markham, while the other two settled about 230 kilometers away in Southwestern Ontario. Eventually one branch of the family – mine – became pioneers again, this time moving to Western Canada.

Robert’s and Elizabeth’s eldest daughter, Elizabeth (1817-1894), married farmer William Oliver (c. 1814-1904), who was from Dumfriesshire. Around 1842, the couple settled in a part of Scarborough that did not yet have a road. They cleared the trees, built a two-story stone house and established a farm that became known for its beautiful flower garden. When they finally sold the property some 35 years later, it brought them more than $100 an acre! They retired to Agincourt, where Elizabeth died of cancer at age 76. They had no children.

In 1842, Janet Hamilton (1818-1897) married Robert Reid (1810-1880), who also came from Lesmahagow. They raised nine children on their farm in Markham. According to her death record, Janet died at age 79 of “old age and heart disease” and all of her sons and daughters died of stroke or heart disease between the ages of 49 and 89.

Agnes Hamilton (1821-1897) married Scarborough farmer James Green (c. 1816-1872) from Dumfriesshire and raised seven children. Agnes’s many grandchildren called her Nannie. When James and his family left Ontario, Agnes’s son James purchased his uncle’s Scarborough property. Agnes died of bronchitis at age 76.

Robert Hamilton (1824-1871) was a farmer like his father, but he left the Scarborough area for cheaper agricultural land in Bosanquet Township, Lambton County. This part of Southwestern Ontario, near the shores of Lake Huron, was opened to settlement in the 1830s, but development was hampered in the early years by a lack of roads. It remained rural, and farmers there grew primarily wheat and peas and raised pigs and cattle. Robert and his wife, Janet Smith (1824-1899), had five children. Shortly after being counted in the 1871 census, Robert died of typhoid fever at age 46. In the 1881 census, the widowed Jennet was listed as “female farmer,” living with her grown daughter and three sons. In many families, the oldest son would be counted as head of the family, but not in this one. Of their children, only James married, and some of his descendants still live in the area today. Robert, his wife and children are buried in Pinehill Cemetery, Thedford, Ontario.

Margaret Hamilton (1827-1891) married James Gordon (c. 1820-1903) and had seven children. They settled in Middlesex County, in Southwestern Ontario, around 1860 and farmed there for 22 years. After selling that property, they purchased a small garden farm. Margaret died at age 64 of angina. Descendants of this family also remain in Southwestern Ontario.

As for James Hamilton (1829-1885), after farming in Scarborough for more than 20 years, in 1882 he became a founding settler of Saskatoon, which at that time was an alcohol-free community of farms surrounding a tiny hamlet. His wife and family moved West the following year. In 1885, James travelled east to visit his relatives and he died there of a heart attack at age 56. He is buried beside his parents in St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Cemetery, Scarborough.

Thus I discovered that the first generation of my Scottish immigrant ancestors were farmers and that most enjoyed long lives, although heart disease made a frequent appearance in their death records. My great-grandfather was the outlier, leaving Ontario for the West long before any other members of the extended family did so. And while his sons went to university and became professionals, the majority of their cousins remained in farming for at least one more generation.

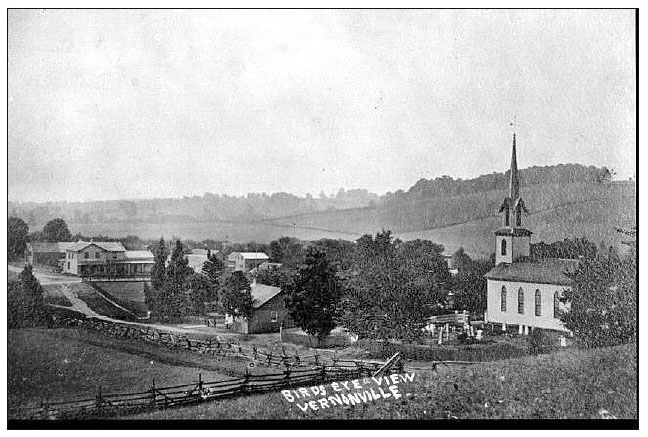

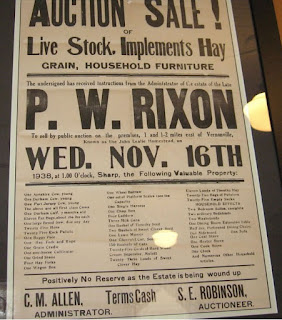

photo credits: Gord Stoll, Alison Mossler Wright

Notes: Here are some suggestions for researching this period of Ontario history.

Local organizations, such as the Scarborough Historical Society, are an invaluable resource. See http://scarboroughhistorical.com.

Several books about the community mention Scarborough’s early settlers by name. See The Township of Scarboro, 1796-1896, edited by David Boyle, Toronto, 1896 (http://www.archive.org/stream/cu31924028900970/cu31924028900970_djvu.txt)

Also, The People of Scarborough: A History, by Barbara Myrvold, published by the City of Scarborough Public Library Board, 1997, gives a comprehensive overview of the community’s history. It is available online as a PDF from the Toronto Public Library.

Scottish baptismal records can be found on Familysearch.org. The image of this church document should be viewed on the Scotland’s People website.

If you find your early Ontario ancestor on Ancestry, you will likely see links to other references to that person, although occasionally the link is to another person with a similar name, or to a son or daughter.

The original marriage documents contain identifying information such as the names of the parents of the bride and groom and occupations.

View census records to see where the family was living every ten years, the name of the current spouse, the names of the children living in the same household, and each person’s occupation. The 1901 census includes the day, month and year of each individual’s birth, although that date may not correspond with other records. Census informants made mistakes. City directories are also useful, although they only list the household head.

Ontario death records from this period can be found on Ancestry.ca by searching the database “Ontario Canada, Deaths and Deaths Overseas, 1869-1948.” Some women are listed under their married names, others under their maiden names. These death documents usually include the date and place of birth as well as the date, place and cause of death.

This article is also posted on https://.genealogyensemble.com and it will be a chapter in a book on the Hamilton family, to be published early next year.