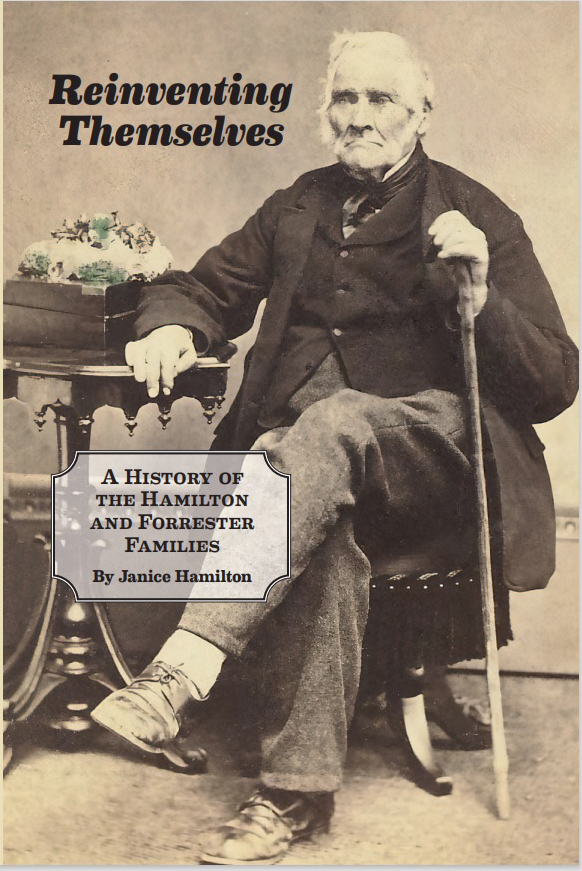

It has been almost 200 years since my paternal ancestors came to Upper Canada from Scotland and took up farming here. It has been about 12 years since I started researching and writing about them. Now that I have pulled all their stories together into the pages of a book, it is time to celebrate.

Earlier this week, relatives and friends helped me launch Reinventing Themselves: A History of the Hamilton and Forrester Families. We got together on Zoom, a solution that was perfect considering that the descendants of this family are spread from Montreal to Toronto, Winnipeg, Vancouver and across the United States.

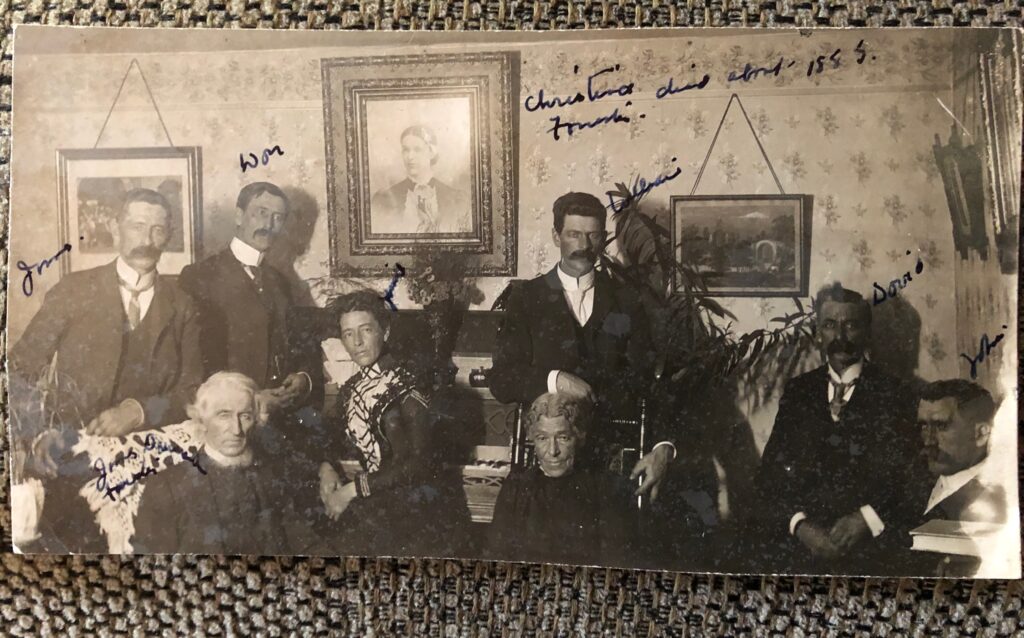

This collection of short articles traces the descendants of weaver Robert Hamilton and carpenter David Forrester. The two Scottish immigrants and their families came to Upper Canada in the 1830s and became part of strong farming communities. Fifty years later, both families moved west. The Hamiltons were founding settlers of a temperance community that eventually became Saskatoon. The Forresters took up prairie farming in southern Manitoba. The following generations continued to reinvent themselves, with several pursuing careers in Winnipeg, Manitoba.

Among them were physician Thomas Glendenning Hamilton and his wife, nurse Lillian Forrester – my grandparents. After their young son died in the 1919 influenza pandemic, the couple began holding seances, and their research into psychical phenomena brought them international fame.

Many of the articles about the Hamilton family have previously appeared on my blog, Writing Up the Ancestors, but pulling them together into a cohesive thread makes the ancestors’ story easier to follow. Much of the material about my grandmother’s family, the Forresters, will be new to most readers.

Reinventing Themselves is available from the online bookstore at https://store.bouquinbec.ca/reinventing-themselves-a-history-of-the-hamilton-and-forrester-families.html. It is $20.00 Canadian for the paperback version, or you can download the e-book for $10.00. Shipping is $6.50 shipping to Canada and $15 to the United States. Most of the books for sale on that site are in French, but the order form is in English.

The process of reinvention is continuing, as the book has inspired two videos. Tracey Arial interviewed me for her podcast Unapologetically Canadian and Frank Opolko, a friend who recently retired from the CBC, also interviewed me.

I learned a great deal while doing this project. Best of all, I discovered several living cousins who were previously unknown to me. One new cousin instantly felt like an old friend, and the mystery person who is my closest match on Family Tree DNA has turned out to be a Forrester descendant from Michigan.

This project reminded me how challenging it is to write about genealogy. All I know about many distant ancestors is their dates and places of birth, marriage and death. While this is essential information, such lists can make for boring reading. The family stories are the good stuff, and they have been the focus of the articles on my blog. Of course, there are two types of family stories: anecdotes that may or may not be true, and well-documented facts.

I was also reminded how much discipline it takes to complete a project of this magnitude. I recently overheard my husband tell someone that he didn’t dare come near my office while I was working on the book because I would chase him away. There are so many distractions, especially on the Internet, that it really takes discipline to stay focused, and a project this size inevitably takes longer than expected.

Now it is time to take a break from family history, catch up on reading novels and enjoying summer before turning my attention to my mother’s family.