A member of my extended family has a silver dish that once belonged to Great Aunt Amelia Bagg (1852-1943), engraved with a genealogical record that goes back to the mid-1700s. Amelia, who was my great-grandfather’s sister, must have been very interested in family history if she went to the lengths of recording this relationship in silver. She also must have been sure of her facts to record them in such an indelible fashion.

The engraving reads:

Margaret, daughter of Thomas and Margaret Friend of Willington,

Married Edward Phillipson of Swalwell;

Margaret Phillipson, their daughter, married Joseph Mitcheson of Langley Park.

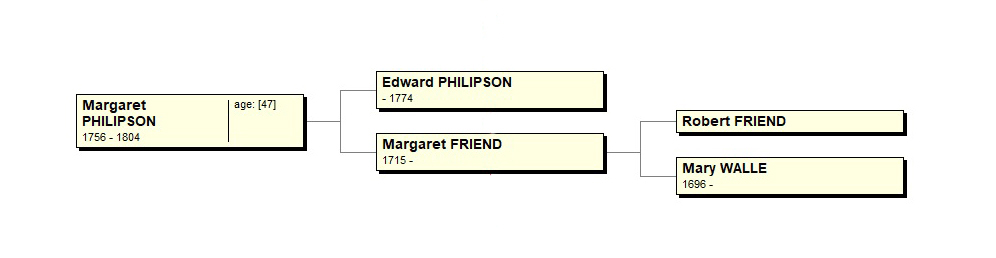

My own research shows that, yes, my direct ancestor Margaret Philipson (1756-1804) married Joseph Mitcheson (1746-1821) in 1774, at Whickham Parish Church, County Durham, in northeast England.1 Furthermore, parish records show that Margaret Philipson was the daughter of Edward Philipson and Margaret Friend.2 However, Amelia may have been wrong about the identity of Margaret Friend’s parents.

My mother’s cousin Clare was also interested in genealogy, especially in the Mitcheson family of County Durham, and she made a list in a notebook of their births, marriages and deaths. The earliest entries in that list were Robert Mitchinson (?-1784) and his wife Mary Waille. Other sources confirm that Robert’s wife’s first name was Mary,3 but when I could not find a record of this marriage, I put a question mark beside Mary Waille’s name.

I now suspect that both aunt Amelia and cousin Clare were partly wrong and partly right. Parish records show that Robert Friend married Mary Walle in Ryton parish in 1714,4 and their eldest daughter, Margaret Friend, was born in 1715. This would explain how Mary Walle/Waille actually fits into the family, and it suggests that Margaret Friend’s father was not Thomas of Willington, as engraved on the silver dish, but Robert of Ryton.

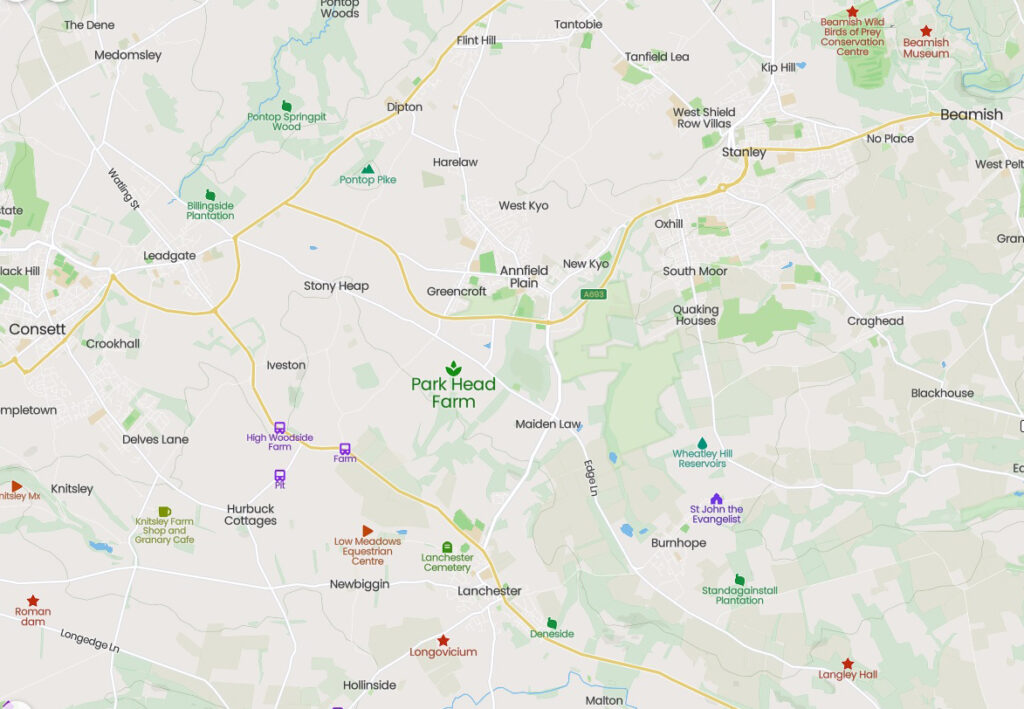

Ryton is in the north of the county, near the towns of Swalwell and Whickham. Willington is south, in the ancient parish of Brancepeth.

There is no question about daughter Margaret Friend’s marriage: she wed Edward Philipson on November 16, 1747 at Whickham Parish Church.5 The couple’s only child, Margaret Philipson, was baptized in 1756, which raises several other questions. Her mother would have been 41 years old that year. Perhaps there had been miscarriages or fertility problems, or perhaps Margaret was not baptized as a newborn, but as a young child. The place and date of Margaret (Friend) Philipson’s death is another unanswered question.

As for Edward Philipson, he may be buried in the cemetery at Whickham Parish Church. A burial entry on the Durham Records Online website (www.durhamrecordsonline.com) reads, “25 July 1774 Edward Philipson, of Swalwell (Crowley’s factory).” This was possibly my ancestor, but what does the reference to Crowley’s factory mean? Did he work there? The factory was a large, well-known manufacturer of iron goods located in nearby Winlaton, but employee records disappeared long ago.

I have not identified a record of Edward’s birth, but I suspect he grew up in the Swalwell area, which was part of the district known as Gateshead. There are records of Philipsons in County Durham and neighbouring Northumberland dating back to the 1677 will of another Edward Philipson, and records suggest that a number of people with the last name Philipson lived in the Swalwell area in the 18th century.

In his will, written in 1803, Joseph Mitcheson noted that Margaret Philipson owned property in the area before they were married, property she probably inherited from her parents. The will stated “I also confirm to my said Wife and her heirs and assigns for ever the freehold and Copyhold houses at Swalwell, Whickham and Winlaton, or elsewhere in the said County of Durham, which belonged to her before our marriage.”6

Records show an Edward Philipson owned a property called Lingyfield House in Swalwell in 1734.7 Land tax records refer to Edward Philipson in Whickham in 17598, and a 1761 poll book listed Edward Philipson, freehold owner of several houses in Swalwell.9

Later records of this family have survived, including the baptisms of Margaret Philipson’s and Joseph Mitcheson’s six children, Margaret’s death in 1804 and Joseph’s death in 1821. Their grave is in Whickham Parish Church cemetery.

Notes:

The children of Joseph Mitcheson and Margaret Philipson were:

Mary (1776-1856), married John Clark and immigrated to Montreal

Robert (1779-1859), immigrated to Philadelphia and married Mary Frances McGregor

William (1783-1857), married Mary Moncaster, was an anchor maker in London

Margaret (1781-1864), married Thomas Dodd of Ryton, Durham

Elizabeth (1786-?) married Shotley, Northumberland farmer John Maughan

Jane (1793-1825) married master mariner David Mainland, died in London

Joseph Mitcheson and Margaret Philipson are my four-times and five-times great-grandparents: cousins-once-removed married, so I am directly descended from both their daughter Mary (Mitcheson) Clark of Montreal and their son Robert Mitcheson of Philadelphia.

Margaret (no maiden name given), wife of Edward Philipson, was buried in 1757 at Kendal, Westmorland, near England’s Lake District. There was a Philipson family in Kendal, but I think this was a different family and a different Margaret.

Several public members trees on Ancestry suggest Edward came from Lincolnshire, but I think it is more likely he was from County Durham.

Sources:

1. England, Select Marriages, 1538-1973 Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.ca, database on-line, entry for Joseph Mitcheson, accessed May 2, 2022), citing England, Marriages, 1538–1973. Salt Lake City, Utah: FamilySearch, 2013.

2. England, Select Births and Christenings, 1538-1975 Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.ca, database on-line, entry for Margaret Philipson, Whickham, accessed May 2, 2022), citing England, Births and Christenings, 1538-1975. Salt Lake City, Utah: FamilySearch, 2013.

3 England, Select Births and Christenings, 1538-1975, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.ca, database on-line, entry for Joseph Mitchinson, Lanchester, accessed May 2, 2022), citing England, Births and Christenings, 1538-1975. Salt Lake City, Utah: FamilySearch, 2013.

4. England, Select Marriages, 1538-1973, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.ca, database on-line, entry for Robert Friend, Ryton, accessed May 2, 2022), citing England, Marriages, 1538–1973. Salt Lake City, Utah: FamilySearch, 2013.

5. England, Select Marriages, 1538-1973, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.ca, search for Margaret Friend, Whickham, accessed May 2, 2022) citing England, Marriages, 1538–1973. Salt Lake City, Utah: FamilySearch, 2013.

6. Will of Joseph Mitcheson, yeoman, Iveston, Durham, The National Archives, Wills 1384-1858 (http://nationalarchives.gov.uk, search for Joseph Mitcheson, accessed Nov. 18, 2010), The National Archives, Kew – Prerogative Court of Canterbury, 9 February, 1822. Ancestry.com.

7. UK, Poll Books and Electoral Registers, 1538-1893, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.ca, database online, entry for Edward Philipson, 1734, Swalwell, image 146, accessed May 2, 2022), citing “London, England, UK and London Poll Books”, London Metropolitan Archives and Guildhall Library.

8 Durham County Record Office. Quarter Sessions – Land Tax Returns, Chester Ward West 1759-1830, www.durhamrecordsoffice.org.uk, for Edward Philipson, Whickham, 1759, (accessed May 2, 2022).

9. UK, Poll Books and Electoral Registers, 1538-1893, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.ca, database online, entry for Edward Philipson, 1761, accessed May 2, 2022), citing “London, England, UK and London Poll Books”, London Metropolitan Archives and Guildhall Library.